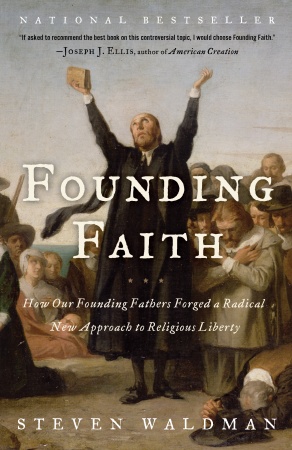

Founding Faith: How Our Founding Fathers Forged a Radical New Approach to Religious Liberty

by Steven Waldman

Long before John Kennedy and Richard Nixon there was another pair of aesthetically mismatched political rivals – James Madison and James Monroe. The two, who would go on to be presidents, faced off in a race to become representatives in the first Congress. Monroe was tall and broad-shouldered, a war hero. Madison was older, frailer, associated with a Constitution that no one in his district liked, and reluctant to campaign because, as he complained to none other than George Washington, he had a bad case of hemorrhoids.

In Founding Faith, Steve Waldman promises realistic portraits of the Founding Fathers, and he delivers.

Waldman captures the early life experiences, spiritual awakenings, and political necessities that shaped the faith of five founders – Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Madison – and put the U.S. on the path to becoming a highly tolerant and pluralistic country, albeit one still struggling with debates over church and state. Like all politicians, they flip-flopped, they disagreed, sometimes deeply, they were born again or doubtful about the divine, and they used language for the sake of opacity rather than clarity. Though they left us with enduring religious liberty, they also left us with a lot of questions unanswered. Or as Waldman puts it, debunking liberal and conservative claims otherwise, their “original intent was, intentionally, murky.”

Religion in early America was boon and curse. Waldman credits it with giving early colonists the will to survive their harsh new environment and the impetus to challenge the British, but he also notes, sometimes with brutal detail, how often religiosity led to persecution of rival Christian denominations and of Jews (other religions, much less atheists, had yet to make much of a mark). Every colony but one had an official or semi-official church; attempts at religious plurality in a handful of colonies unraveled.

The founders reflected the religious diversity and drama of the time, Waldman notes in brief biographical sketches, coming from different traditions and coming to different conclusions about them. None of them was a true Deist, as liberals often claim, nor were they all sold on Jesus as the savior, as conservatives say. All of them not only promoted but used religious liberty to explore their own beliefs and debate the role of religion in their new governments. (And of course, four of them would go on to be presidents, applying those beliefs differently.)

In such a context, to promote a unified theory of religious liberty was a daunting task. The founders were helped somewhat by the exigencies of war, Waldman notes. Washington promoted religious tolerance in the Continental Army – the first truly national institution – out of necessity. The colonies united using religious language and metaphors as motivation. And the Continental Congress, trying to encourage defections, promised and promoted religious freedom to mercenaries serving the British.

Waldman devotes a good bit of his book to the political machinations of the founders as they wrote the country’s founding documents before and after the war -the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The Declaration, Waldman notes, was a product of compromise, including both “divine providence” and “Supreme Judge,” two quite distinct notions of divinity that reflected the divisions among the founders and Americans. “If you can’t decide between a biblical, interventionist God and an aloof Deistic God,” Waldman says jokingly, “simply appeal to both!” Religion was rarely discussed in the Constitutional Convention, and the only mention of religion in the Constitution is to ban religious tests for political office. “[The] stubborn refusal of the U.S. Constitution to invoke the Almighty,” Waldman writes, “is abnormal, historic, radical, and not accidental.”

It was the Bill of Rights that required the most “sausage grinding,” and that made it clear how important Madison was, in particular, to securing religious liberty. He may have failed at his most ambitious objective – protecting religious freedom in the states by giving Congress a veto over state laws, and by amending the Constitution. And Jefferson may have been responsible for giving us our dominant metaphor on the relationship between church and state – the “wall of separation.” But it was Madison who fought for the Constitution and the Bill of Rights (after initially being against it), and united the founders’ competing philosophies on religious freedom, using that deliberate murkiness of politicians. “Why did you agree to language that could be interpreted in so many different ways? Surely you understood that such ambiguity would bedevil the next generations. Why not just clarify what the hell you meant,” Waldman asks of Madison. The answer? “Because he needed the votes.”

Excerpt: “Is it paradoxical that someone so spiritually dispassionate became the nation’s most zealous champion of religious liberty? On the contrary, Madison in some ways had the perfect combination of personal characteristics to play this role. Because he deeply respected religious people and religion–studying it avidly–he wanted to preserve its expression and health. But because he wasn’t intensely attached to a particular approach, he could embrace pluralism and the marketplace of spiritual ideas. And, perhaps most important, he was humble. While other Founders used their formidable minds to comprehend God and His ways, Madison seemed, earlier than the others, to resign himself to accepting the limitations of his understandings.”

Further Reading: The Jefferson Bible: The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth and American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation

Send A Letter To the Editors