Rising income inequality is a global phenomenon, but it’s worse in the U.S. than anywhere else. What is behind the growing gap between rich and poor Americans? According to New Republic editor Timothy Noah, it all began in the late 1970s. Noah visits Zócalo to discuss whether wealth disparity matters and how we can keep it from growing. Below is an excerpt from his book, The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It.

The fact is that income inequality is real; it’s been rising for more than 25 years.

-President George W. Bush, January 2007

During the past 33 years, the difference in America between being rich and being middle class became much more pronounced. People with high incomes consumed an ever-larger share of the nation’s total income, while people in the middle saw their share shrink. For most of this time the phenomenon attracted little attention from the general public and the press because it occurred in increments over one-third of a century. During the previous five decades-from the early 1930s through most of the 1970s-the precise opposite had occurred. The share of the nation’s income that went to the wealthy had either shrunk or remained stable. At the first signs, during the early 1980s, that this was no longer happening, economists figured they were witnessing a fluke, an inexplicable but temporary phenomenon, or perhaps an artifact of faulty statistics. But they weren’t. A democratization of incomes that Americans had long taken for granted as a happy fact of modern life was reversing itself. Eventually it was the steady growth in income inequality that Americans took for granted. The divergent fortunes of the rich and the middle class became such a fact of everyday life that people seldom noticed it, except perhaps to observe now and then with a shrug that life was unfair.

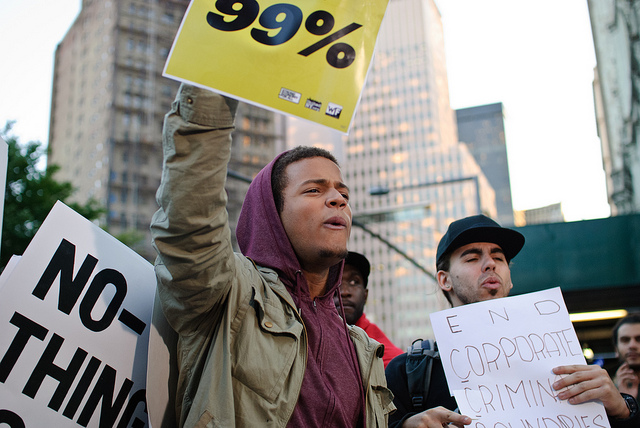

There were signs that this indifference was beginning to evaporate in the fall of 2011, when protestors turned up on Wall Street waving signs that said we are the bottom 99 percent. As I write, it’s too early to say whether the Occupy Wall Street movement will have any lasting positive effect, but certainly the topic is becoming more difficult to ignore. “I am 21 and scared of what the future will bring,” read one testimonial posted online by a protester. “I work full time with no benefits, and I am actively looking for a second job, because I am barely making it. I worry every month that I will not be able to afford rent. I am afraid of what will happen if I get sick. I am afraid I will never be able to go back to school.” Another read: “My parents have worked hard their entire lives as small business owners. In hard times they ALWAYS paid their employees before themselves. They would like to retire soon but can’t afford to stay in the modest ranch house they have lived in for 35 years. We are currently making renovations to our house so they can move in and avoid Section 8 [low-income] housing.” The day before these statements appeared on the Web, The New York Times evaluated for its more affluent readers the pluses and minuses of Kohler’s new $6,400 luxury Numi toilet, which featured two flushing modes, an automatically rising toilet lid, and stereophonic sound.

We tend to think of the United States as a place that has grown more equal over time, not less, and in the most obvious ways that’s true. When the republic was founded, African Americans were still held in bondage and were defined in the Constitution as representing three-fifths of a human being. Only adult white male property owners could vote. Over the next two centuries full citizenship rights were extended gradually to people who didn’t own property, to blacks, to women, and to Native Americans. In recent years, gay activists have fought at the state level for the right to same-sex marriage, and they’ve prevailed, at this writing, in six states and the District of Columbia. It seems just a matter of time before this right is extended in the rest of the country. Difficult to enforce, the principle that all men and women are equal before the law is even more difficult to refute. All the groups mentioned here experienced setbacks in their pursuit of legal equality, some lasting as long as a century. Few people belonging to any of these groups would argue that this pursuit ends with the removal of explicit legal barriers. Still, most would likely agree that over the long haul, legal obstacles to full and equal participation in American life tend to diminish.

It was once possible to make a similar argument with respect to economic obstacles. As late as 1979, the prevailing view among economists was that incomes in any advanced industrial democracy would inevitably become more equal or remain stable in their distribution. They certainly wouldn’t become more unequal. That sorry fate was reserved for societies at an earlier stage of development or where the dictatorial powers of the state preserved privilege for the few at the expense of the many. In civilized, mature and free nations, the gaps between rich, middle class, and poor did not increase.

That seemed the logical lesson to draw from U.S. history. The country’s transformation from an agrarian society to an industrial one during the late 19th and early 20th centuries had created a period of extreme economic inequality-one whose ramifications can still be glimpsed by, say, pairing a visit to George Vanderbilt’s 125,000-acre Biltmore Estate in Ashville, North Carolina, with a trip to the Tenement Museum on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. But from the early 1930s through the early 1970s, incomes became more equal, and remained so, while the industrial economy lost none of its rude vitality. As the 1970s progressed, that vitality diminished, but income distribution remained unchanged.

“As measured in the official data,” the Princeton economist Alan Blinder wrote in 1980, “income inequality was just about the same in 1977 … as it was in 1947.” What Blinder couldn’t know (because he didn’t have more recent data) was that this was already beginning to change. Starting in 1979, incomes once again began to grow unequal. When the economy recovered in 1983, incomes grew even more unequal. They have continued growing more unequal to this day.

The United States is not the only advanced industrialized democracy where incomes have become more unequal in recent decades. The trend is global. A 2008 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which represents 34 market-oriented democracies, concluded that since the mid-1980s, income inequality had increased in two-thirds of the 24 OECD countries for which data were available, which included most of the world’s leading industrial democracies. But the level and growth rate of income in equality in the United States has been particularly extreme.

There are various ways to measure income distribution, and by all of them the United States ranks at or near the bottom in terms of equality. The most common measure, the Gini coefficient, is named for an Italian statistician named Corrado Gini (1884-1965). It measures distribution-of income or anything else-on a scale that goes from zero to one. Let’s imagine, for instance, that we had 50 marbles to distribute among 50 children. Perfect equality of distribution would be if each child got one marble. The Gini coefficient would then be zero. Perfect inequality of distribution would be if one especially pushy child ended up with all 50 marbles. The Gini coefficient would then be one. As of 2005, the United States’ Gini coefficient was 0.38, which on the income-equality scale ranked this country 27th of the 30 OECD nations for which data were available. The only countries with more unequal income distribution were Portugal (0.42), Turkey (0.43), and Mexico (0.47). The same relative rankings were achieved when you calculated the ratio of the highest income below the threshold for the top 10 percent to the highest income below the threshold for the bottom 10 percent. The United States dropped to 29th place (just above Mexico) when you calculated the ratio of median income to the highest income below the threshold for the bottom 10 percent. When you calculated the percentage of national income that went to the top 1 percent, the United States was the undisputed champion. Its measured income distribution was more unequal than that of any other OECD nation. As of 2007 (i.e., right before the 2008 financial crisis), America’s richest 1 percent possessed nearly 24 percent of the nation’s pretax income, a statistic that gave new meaning to the expression, “Can you spare a quarter?” (I include capital gains as part of income.) In 2008, the last year for which data are available, the recession drove the richest 1 percent’s income share down to 21 percent. To judge from Wall Street’s record bonuses and corporate America’s surging profitability in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, income share for the top 1 percent will resume its upward climb momentarily, if it hasn’t already. We already know from census data that in 2010 income share for the bottom 40 percent fell and that the poverty rate climbed to its highest point in nearly two decades.

In addition to having an unusually high level of income inequality, the United States has seen income inequality increase at a much faster rate than most other countries. Among the 24 OECD countries for which Gini coefficient change can be measured from the mid-1980s to the mid-aughts, only Finland, Portugal and New Zealand experienced a faster growth rate in income inequality. Of these, only Portugal ended up with a Gini rating worse than the United States’. Another important point of comparison is that some OECD countries saw income inequality decline during this period. France, Greece, Ireland, Spain, and Turkey all saw their Gini ratings go down (though the OECD report’s data for Ireland and Spain didn’t extend beyond 2000). That proves it is not woven into the laws of economics that an advanced industrial democracy must, during the present epoch, see its income inequality level fall, or even stay the same. Some of these countries are becoming more economically egalitarian, not less, just as the United States did for much of the 20th century.

Buy the Book: Skylight Books, Powell’s, Amazon.

Copyright © 2012 by Timothy Noah. Reprinted by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.

*Photo courtesy of Alison Brockhouse.

Send A Letter To the Editors