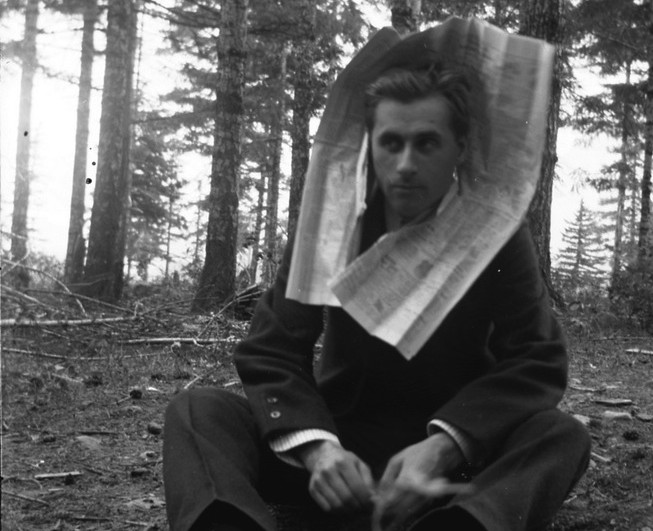

There is some news we can’t escape. Flip on the TV at 6:00 p.m., and you’ll be confronted with every sordid detail of the latest political sex scandal. Read the newspaper online and just try to avoid the headlines about the Kardashian clan. And when a topic trends (in 140 characters) on Twitter, the buzz can be deafening. In advance of the Zócalo/Getty Center event “Is the News Driving Us Crazy?”, we asked media savvy folks to tell us what recent story (or type of story) drove them especially crazy—and what they’d rather find in the headlines.

On December 6, 2013, the Washington Post ran a story with the following headline: “Washington’s Super Bowl drought the product of karma or curse?”

The 21st century is underway. Shouldn’t we have moved beyond the discussion of curses? It is bad enough that recent Bud Light commercials celebrate the odd notion that the behavior of individual fans watching a game on television can influence its outcome. Can’t we expect more from our journalists—even our sports journalists?

Ballplayers, I realize, can be a superstitious lot. Fans, too. Remember the “Curse of the Bambino”? After the Boston Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees, that curse allegedly prevented the Red Sox from winning the World Series … until … until they got some really good players. But journalists are supposed to be engaging in nonfiction—not mythology.

In the Washington Post story, the writer considered a downturn in the fortunes of the Washington Redskins football team in the context of the debate about their name—which is seen as derogatory to Native Americans. And he was having some fun. His tongue, in my reading, was somewhere in the vicinity of his cheek. Humor is certainly better than devoutness when speaking of curses. But still. …

Sports journalism has improved in recent decades with the introduction of advanced statistical analysis. Sports reporters have the freedom to enumerate the management failings that often limit teams like the Redskins. And politics—as in the debate about this team’s name—also now finds its way to the sports pages. Can’t we stick to these explanatory systems and give the “karma” and “curses” a rest? Can’t we leave behind—even when having some tongue-in-cheek fun—tired and retrograde recourses to superstition?

Journalism should, when the opportunity presents itself, be challenging ignorance and superstition—not encouraging them.

Mitchell Stephens, a journalism professor in the Carter Institute at New York University, is the author most recently of Imagine There’s No Heaven: How Atheism Helped Create the Modern World, just published by Palgrave Macmillan.

The Washington Post recently ran a story headlined “In San Jose, generous pensions for city workers come at the expense of nearly all else.”

The story’s summary paragraph set a new standard in newspaper hyperbole: “In San Jose and across the nation, state and local officials are increasingly confronting a vision of startling injustice: Poor and middle-class taxpayers—who often have no retirement savings—are paying higher taxes so public employees can retire in relative comfort.” There is no quote from someone asserting that this startling injustice exits. It is offered as a plain statement, as a fact.

Down in the 17th paragraph, there is this revelation: “Meanwhile, public pension benefits statewide average just $2,600 a month—a reasonable sum, union officials say, given that many retirees are not eligible for Social Security.”

This story, like much of the reporting on pensions, basically chronicles the debate as laid out by major players. In a matter as important as this, that is not good enough. Journalists must elevate the debate by asking more penetrating questions.

California public employee pension funds paid asset managers more than $3 billion in fees in 2013. These fees, or the benchmarks by which these managers are compensated, are seldom questioned by the news media or the laypeople who serve as volunteer pension fund board members. This is where the resources and expertise of a robust news organization can be of great public service. Defined contribution plans (401(k)-type plans) are also largely given a pass. Can private companies, whose CEOs now rake in eight figures in annual compensation, really not afford traditional pensions?

There are many questions to be raised about turning retirement plans into a mass societal casino night. But until the news media raises more of those questions in their coverage of the pension issue in California, we won’t get an honest accounting of the costs and benefits of employee pensions. Rather than simply amplify what interested parties are saying, journalists can dig deeper to tell us what is not being said in public.

Peter Hong is a Los Angeles writer. He spent 20 years as a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and Business Week.

For more than a week, the technology world has been buzzing about the news of Facebook’s purchase of messaging service WhatsApp for $16 billion. People are asking: What does it mean for the future of Silicon Valley? Did Facebook pay too much?

But another story deserved far more attention than Facebook’s long march to global social networking dominance. This week, a technology that could potentially create children with three genetic parents came under scrutiny by a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel.

“Three-parent IVF” is a technique that uses one woman’s egg, another woman’s mitochondrial material, and a man’s sperm to create a viable embryo—and allow women who carry mitochondrial DNA mutations to avoid passing them on to their children. In order to decide whether or not to give scientists permission to conduct human clinical trials, the FDA focused on the safety and efficacy of the technique. But the panel failed to explore important questions of morality and ethics. The few brief articles that appeared in the news mentioned the ethical issues only in passing.

Many critics of three-parent IVF have raised the specter of “designer babies,” noting the technique’s potential to normalize acceptance of other genetic tinkering. The media missed an opportunity to encourage further public debate about this important issue and to deepen the discussion of human genetic manipulation and its consequences. Technology is more than Google, Twitter, and Facebook. Sometimes, it poses the possibility of altering the face of humanity itself.

Christine Rosen is a Future Tense fellow at the New America Foundation.