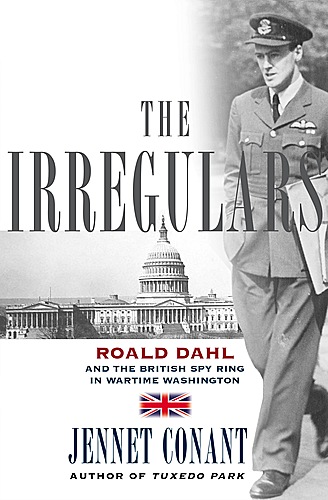

The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington

by Jennet Conant

Roald Dahl was only 25 when he arrived in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1942, wounded and disappointed. He had fought fierce battles in the Royal Air Force, of whom Winston Churchill had said, “never in the field of human conflict was so much owed to so few.” Grounded with a head injury and reassigned as a “whiskey warrior” with the British Embassy, Dahl considered himself demoted. He regarded the job with disdain and managed to annoy officials on both sides of the pond within months.

It was an inauspicious start to Dahl’s dizzyingly successful career as a spy, which preceded his dizzyingly successful and seemingly incongruous career as a writer of children’s fiction. Within three years, Dahl won the trust of well-connected insiders, bedded, in the words of a friend, every woman “on the East and West coasts that had more than fifty thousand dollars a year,” and was a regular guest of Franklin Roosevelt.

Jennet Conant’s The Irregulars tells Dahl’s fascinating story at the brisk clip of the best mystery novels. Conant indulges in the glamor of and nostalgia for that distant past – when newsmen were powerful and envied personalities, when handsome young agents cavorted with heiresses and congresswomen, all for the preservation of the free world – without falling for it, maintaining instead a healthy humor and skepticism.

The spy ring of which Dahl became a member, along with future James Bond novelist Ian Fleming and ad man David Ogilvy, had no particularly rigorous method of selecting its agents, behaving, in Conant’s terms, “like a club voting in new members.” But their job was a big one: to push Americans toward active participation in a war still considered by many to be a distant European matter.

Once Dahl was in, his D.C. became a pageant of strange and well-known characters whom Conant weaves cleverly through the plot, plucking keen details. Charles Marsh, Dahl’s mentor and father figure, was “classically ugly in a way that was compelling.” The two constantly wrote letters to each other, including one ribald exchange that Conant calls an “epistolary circle jerk.” Harry Truman enters as a senator from Missouri, robbing Dahl of his first magazine paycheck for $900 in a game of poker. Drew Pearson, who had goldfish named after Roosevelt’s aides and a cow named after the First Lady, dined often with Dahl at the Mayflower. Socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean greets him at her Sunday night dinners wearing the Hope diamond. Dahl ate “caviar from a two-kilo tin” with Ernest Hemingway. A female cousin of Roosevelt’s, who “had purple hair, wore trousers, and owned thirty red setters,” hosts Dahl and the president for stiff drinks.

It’s especially fun to read of Dahl’s women. There is, of course, his first wife Patricia Neal, possessed of an amusingly sharp tongue. Conant quotes her as saying Dahl “could be like the sand in an oyster.” And then there are the other women. Dahl went to a party with “Eisenhower’s girlfriend,” and Standard Oil heiress Millicent Rogers granted him a “Tiffany gold key to her front door.” He shacked up with Connecticut congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce, wife of Time and Life publisher Henry Luce and staunch opponent of the British Empire. He was left so exhausted by her sexual appetites that he begged his boss to take him off the “assignment.” The boss refused.

Conant wraps up the post-war story with merciful quickness; it was a tragic time for Dahl, who lost his mentor and his daughter, whose wife and son are felled by devastating accidents. Dahl was left disappointed by President Truman’s decision to build the CIA instead of sticking with the OSS, and by the U.S.’s aggressive attitude toward Russia and reluctance to grant war aid to Britain. By the conclusion of the book, Dahl is the man more popularly known to generations of children: elderly, a slight curmudgeon in a cardigan, and the inventor of beloved and lively stories that nonetheless could not compete with the one he lived.

Excerpt: “He had been a gambler all his life. When he had worked for the Shell Oil Company offices in London as a trainee in 1934, he had regularly placed bets by phone on the two o’clock horse race and would sneak out of the office in late afternoon to check the results in the first evening paper. He had succeeded in beating long odds in his first tour of duty. Why not try his luck again? He had no training or experience that qualified him in any way for this duplicitous line of work, but as he later wrote, by that stage of the war ‘an RAF uniform with wings on the jacket was a great passport to have.’ It would provide all the cover he needed.”

Further Reading: 109 East Palace and The Puzzle Palace

Send A Letter To the Editors