On October 2, 1950, the first Peanuts comic strip was published. Penned by Charles “Sparky” Schulz, the first strip foreshadowed all the strange, sad ordinariness that would come: two children watch Charlie Brown stroll by with a smile, call him “good ol’ Charlie Brown,” and as he passes, one frowns and says, “How I hate him!” Below, an excerpt from David Michaelis’s Schulz and Peanuts: A Biography explores the the impact of the strip, particularly the antics of Snoopy in the 1960s.

In a very midwestern way, Schulz reversed the American pattern of winners and losers, making a virtue of the fortitude required to endure blowing a hundred ball games in a row. The very notion embedded in You Can’t Win, Charlie Brown turned the traditional East Coast orthodoxies of American children’s literature inside out; in the creed of Louisa May Alcott, everything came out right in the end, but in Peanuts, the game was always lost, the football always snatched away. In Charlie Brown’s world, the kite was not just stuck in a tree, it was eaten by it; the pitcher did not just give up a line drive, he was stripped bare by it, exposed.

Now, in 1966, as Snoopy pantomimed people to themselves from the doghouse roof – no longer the merely subversive impersonations of the ’50s but acting out the Flying Ace’s full-fledged crusade – Peanuts acquired an explanatory as well as a descriptive character for thousands who burned draft cards and protested an unjustifiable war.

While mission upon mission of B-52 bombers hammered North Vietnam’s capital and primary port cities, Snoopy’s mania, his single-minded pursuit of the enemy and his hatred of losing, epitomized the America haunted by an always victorious John Wayne, the postwar U.S.A. that was racing to beat the Soviets to the moon.

As Snoopy soared – and danced – Peanuts once again led the culture. If the World War I Flying Ace mocked the martial spirit of the great War, Snoopy’s spontaneous, soul-satisfying dances of the ’60s made him a genuine free spirit whose only commitment was to ecstasy itself.

His flutter-footed step kept time to bliss itself, lifting him so high above the “over-thirty” concerns of his strip mates, he hardly seemed to notice that he was leaving reality – and petty old Lucy – in the dust….

Peanuts in the new age of Snoopy was bolder but still quietly dissident, laying claim to joy, pleasure, naturalness, and a self-glorifying spontaneity without the feroocious exhibitionism that most radicals and rebels of the period deemed necessary to bring attention to their causes. Snoopy’s basic desire – to transcend his existence as a dog by altering his consciousness – typified a central urge of the era and caused alarm among the strip’s authority figures no less than its analogs did in the “real world”…

“The strip’s square panels were the only square thing about it,” reflected the novelist Jonathan Franzen, who, “like most of the nation’s ten-year-olds,” was growing up through those “unsettled season[s]” of the ’60s by taking refuge in “an intense, private relationship with Snoopy” – a stronger attachment than that which the reader could have with any of the other Peanuts characters because Schulz was now making us Snoopy’s accomplices in transcendence. We alone can see what the Flying Ace is seeing; everyone else in the strip, even Charlie Brown, remains blind to the identity and miraculous feats of the “Masked Marvel,” the Easter Beagle, the World-Famous Astronaut, the World-Famous Wrist Wrestler, Joe Cool, Flashbeagle, “Shoeless” Joe Beagle, and the Scott Fitzgerald Hero.

Snoopy had his origins in Spike, the dog of Schulz’s youth, whom Sparky called “the wildest and the smartest dog I’ve ever encountered,” and as long as Snoopy was treated as a pet – an eccentric, even a lunatic, household dog – by the Peanuts gang, he evinced Spike-like behavior. But now he left the kids behind….

This was the first time in the comics that an animal had trumped its humans. Never before had an animal taken over a human cartoon, and “it did more than change Peanuts,” said Walter Cronkite, “it changed all comics.” Schulz’s fellow cartoonists read and reread the Red Baron episodes to figure out how Sparky was getting away with it. His rival Mort Walker looked on, dismayed. The gag-minded creator of Beetle Bailey had been able to follow along with Schulz when Snoopy was perched in a tree, pretending to be a vulture. But a dog…flying a Sopwith Camel that was actually a doghouse, which he couldn’t sit on, anyway? “That’s when I realized I didn’t know anything about the comic business,” said Walker. “What does a dog know about World War I and the Red Baron? Where did he get the helmet?”

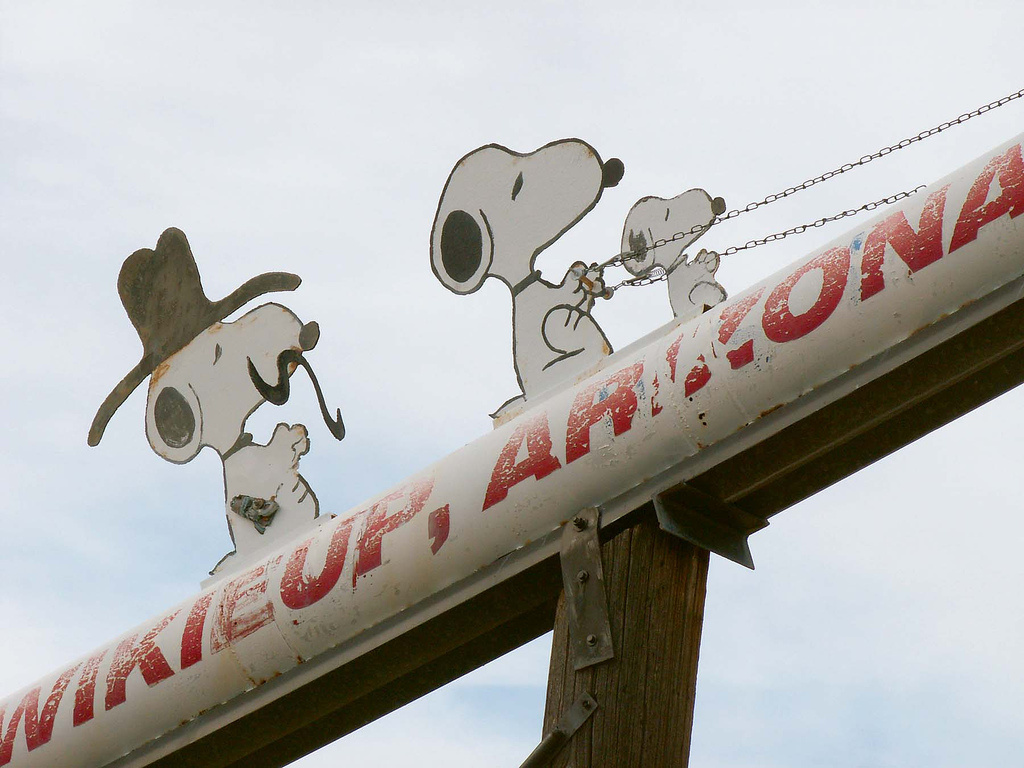

*Photo courtesy cobalt123.

Send A Letter To the Editors