The meaning of Gandhi has been hotly debated ever since his death, but one thing is certain: his pioneering concept of satyagraha, or nonviolence, continues to inspire activists and protesters today. Joseph Lelyveld’s new biography, Great Soul, has ignited controversy over Gandhi’s human side, so in advance of Lelyveld’s appearance at Zócalo on April 12, we asked two experts to evaluate his life and legacy.

Let’s Evaluate Him on His Ideas, Not His Sex Life

I read Lelyveld’s biography as soon as it appeared because I was eager to include an assessment of it in a bibliographical essay for the next edition of my study of Gandhi’s political theory out soon. Great Soul impressed me as being a fair, fluent and well researched account of Gandhi, striking a fine balance that appreciated his signal achievements – especially the salt march and Calcutta fast, his most dramatic satyagrahas – yet introduced criticisms of his early views in South Africa that were fair and penetrating. I subsequently wrote that it was the best biography by an American or British journalist since the classic by Louis Fischer.

Lelyveld inevitably lacks what Fischer featured, a direct personal relationship with Gandhi, but even more than Fischer, Lelyveld is determined to get the story right. This is evident, for example, with the precision that he relentlessly tracks the twists and turns of Gandhi’s attitudes toward race during his initial period in South Africa. Lelyveld does recognize the central theme of all great biographies of Gandhi, that his life was a journey marked by unusual changes. My main criticism, aside from the book not including interviews with Gandhi’s contemporaries, is that it could have emphasized even more the extent that many of Gandhi’s ideas underwent such drastic transformations after he left South Africa. His mature thought and leadership left behind basic attitudes toward caste and race to develop into an extraordinarily inclusiveness. The sheer imagination of this thinker and activist is staggering.

With this assessment of his book in mind, I read the review of it by Andrew Roberts, “Among the Hagiographers” in The Wall Street Journal on March 26. My astonishment began with the opening paragraph that called Gandhi a “sexual weirdo, a political incompetent … professing his love for mankind as a concept while actually despising people as individuals.” I was surprised not by the tenor and tone, because Gandhi’s enemies in India during his lifetime had spewed worse. (After all, the conspirators that assassinated him openly expressed extreme hatred for the man they firmly believed had singlehandedly betrayed their country.) What surprised me, then, was the fact that The Wall Street Journal, to which I had subscribed until March 26, published such an irredeemably venomous review, enabling a person with little knowledge of Gandhi to push a personal agenda. (My faith in journalism generally was soon restored by other reviews.)

At the end of this controversy, though, remains a query: how long will the obsession with Gandhi’s sex life continue? The judgment of history is already being made about Gandhi, helped by books like Great Soul, and it seems incredible that the original ideas and remarkable leadership he provided could possibly hinge on whether or not he was bisexual. Perhaps we need brilliant humorists like Oscar Wilde or Mark Twain to get some perspective.

Dennis Dalton is professor emeritus of political science at Barnard College specializing in political theory, nonviolence and the life of Gandhi.

—————————————————————————————————————

Just Look at the Middle East Protests

Although Gandhi is a controversial figure whose legacy has often been disputed, his reputation has in general increased in the years since his assassination in 1948. He is revered today by many as a spiritual leader and saintly figure. He is seen by others as a great pacifist. He is admired for his method of militant nonviolent resistance – satyagraha – and many have sought to apply it in struggles for civil and democratic rights. He has been held up as a champion of national liberation who has provided a potent means for resisting colonial rule. Others have appreciated his critique of the industrial mode of production and his call for a self-sustaining economy and egalitarian society.

Ghandi’s philosophy of satyagraha, or nonviolent resistance, is of particular relevance today. His creation of a new word in English, that of “nonviolence” – which he took from the Sanskrit ahimsa – has become the standard term to describe such that form of protest. Gandhi evolved a range of techniques and strategies that were tried and tested in actual protests in South Africa and colonial India. They were developed further by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., and the foremost political theorist in this area, Gene Sharp. And, of course, Gandhi’s continuing influence in this respect can be seen in the ongoing protests in the Middle East and north Africa, where manuals on the strategy of nonviolent resistance that are directly inspired by Gandhi’s methods have been circulated and applied to telling effect by protestors. Gandhi’s struggle against colonial and racial oppression provides in this respect a beacon that continues to inform ongoing struggles for democracy and civil liberties in the face of authoritarian repression.

David Hardiman is professor of history at University of Warwick specializing in subaltern studies.

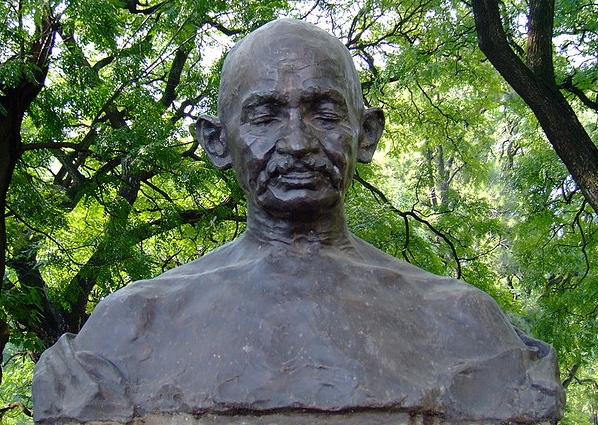

*Photo courtesy of Elton Melo.