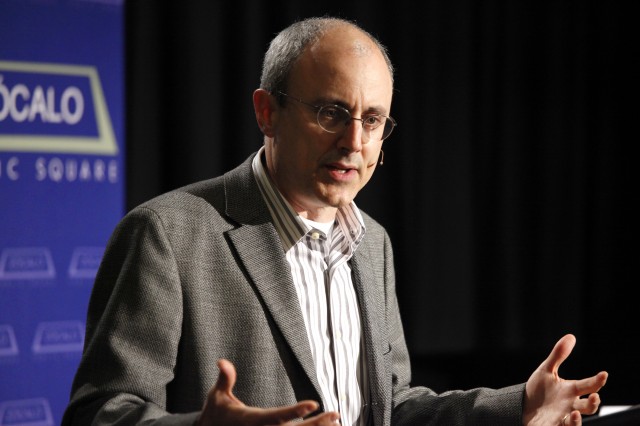

What makes oil-producing countries different from other countries–and why would something as ostensibly beneficial as oil wealth be bad? It’s not a coincidence that a lot of oil lies beneath the ground of the world’s more volatile countries, said UCLA political scientist Michael Ross, author of The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations. And neither Western intervention nor multinational corporations are to blame.

Rather, Ross told a crowd at the Goethe-Institut Los Angeles, oil is bad for developing countries because of “the extraordinary power and the kinds of revenues that oil wealth generates for governments” and the opacity of the entire industry.

“If you’re like me, you sometimes go to Target, and there’s a funny thing about what you buy there,” he said. “Every single thing in that entire store, no matter the smallest trinket or the biggest appliance, comes with a tag that says where it comes from.” U.S. laws ensure that every item you purchase states its country of origin. Yet every time we go to the pump, we have no idea where our gas is coming from.

The oil industry is worth $2 to 3 trillion per year, and many of the largest companies in the world are oil companies. “Yet it’s also one of the least transparent industries,” said Ross.

In 1980, oil-producing countries were not much different from the rest of the world. And although the entire developing world has become more democratic and less dangerous in the past three decades, oil-rich developing nations like Sudan, Iraq, and Libya are bearing the brunt of a larger fraction of the world’s violence.

In the 1970s, almost all oil-producing countries nationalized their oil industries and expelled foreign firms amid big celebrations. But the power previously held by multinational companies was transferred not to the citizens but to incumbent governments that took advantage of their windfalls to grow bigger and wealthier–and more authoritarian and corrupt. Life wasn’t any better when corporations ran the show, said Ross–but neither did nationalization help most people.

Saddam Hussein came to power from a relatively obscure bureaucratic position because he was in charge of Iraq’s nationalization process; Muammar Qaddafi was the same story in Libya.

Ross asked the audience to “imagine two countries identical in most respects, except one has oil wealth and the other only has manufacturing and other industries.” The petroleum-producing country’s government is twice as large a fraction of their economy as the other country’s government. That revenue comes not from tax dollars–which force governments to become accountable to their citizens–but from oil. Democracy evolves from citizens demanding knowledge about where their money is going. But “if you’ve got lots of oil wealth, you are a government that can fund yourself without worrying about what the people do or don’t want,” said Ross. And because of the opacity of oil revenues, governments don’t have to bother including that money in the budgets they make public. Instead, in countries like Hussein’s Iraq and Chavez’s Venezuela, oil money moves through secret channels.

Oil money has also allowed governments to put down uprisings more successfully. In Algeria, the government offered people subsidies and handouts when they began to rise up–and also had the advantage of a larger and better-funded military. “Countries that have oil spend about 50 percent more on their military than countries without oil,” said Ross, which also helps keep the militaries in oil-rich countries loyal to the incumbent government.

“Is this sort of an iron law of geology: the fate of countries is driven by their soil and climate and so forth?” asked Ross. “I certainly don’t think so.” Oil demand production is going to continue to increase in the next 20 years by a third, meaning that as many as two dozen developing countries will begin producing oil. These countries–like Sierra Leone, Mozambique, Cambodia, and South Sudan–can use their wealth to the benefit of their citizens, but only if the rest of the world puts in place sanctions and policies that require transparency and prevent oil revenues from going directly to governments.

“I’m not going to ask you all to pledge to buy Priuses and electric cars,” said Ross. “But if you’re a U.S.-based company, you have to publicly disclose how much money you’re paying foreign governments for oil.” The financial regulation of 2010’s Dodd-Frank Act required the SEC to issue rules for accountability, but the laws have yet to be written, because oil companies have threatened to sue.

In the question-and-answer session, audience members challenged Ross to further defend his argument.

Ross was asked if some of these problems are caused by “Dutch disease,” a phenomenon in which countries rich in natural resources have trouble profitably exporting other goods. This is not an automatic economic phenomenon, Ross responded–and this wouldn’t be a problem if oil were a completely benign basis on which an economy could rest. But how has oil-rich Norway avoided these problems? Oil doesn’t make life worse in countries that are already well-governed and democratic, said Ross–but for low- and middle-income countries, the government isn’t prepared to be held accountable to the people and lacks the bureaucratic capacity to manage huge flows of cash.

Watch full video here.

See more photos here.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Amazon, Powell’s.

Read experts’ opinions on what the Middle East would look like if nobody needed the region’s oil here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors