If no good deed goes unpunished, no good diplomatic deed goes unopposed, and certainly the ferocity of opposition to the tentative nuclear deal between Iran and the international community (represented by the so-called “P5 + 1,” the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany) may be a meaningful accomplishment. The deal, reached in Geneva in December, is under attack from a number of domestic lobbies and third-party spoilers, principally Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Under the terms of the deal, Iran has agreed to lower all of its enrichment activity to 5 percent of its previous activity, dilute its stockpile of nearly 20 percent-enriched uranium, halt the installment of additional centrifuges, and stop any further work on the construction of a heavy-water reactor facility in the city of Arak. In return, Western nations have agreed to provide targeted and limited relief from crippling economic sanctions against the Islamic Republic targeting its oil and financial industries.

In other words, as significant as it may be, the interim agreement is just that—an interim agreement, largely a confidence-building measure on the way toward comprehensive negotiations.

Inspections of Iran’s nuclear facilities began on January 20, and the results, thus far, are in accord with the provisions set forth in the Geneva agreement. In response, the U.S. government has recently announced that it will hold up its end of the bargain by loosening its sanctions ($7 billion worth) against Iran’s ailing banking sector, allowing for limited financial exchanges with Western firms.

The Geneva agreement, meanwhile, has been met with criticisms and commendations in equal measure. For Western opponents of the deal—largely channeling the anxieties of Israeli and Saudi leaders—the deal rewards bad behavior insofar as it does not require an immediate suspension of all enrichment activities. Critics say that it instead affords the Iranians more time to advance their nuclear program. Curiously enough, hardline politicians inside Iran have opposed the deal for precisely the opposite reason: namely, that it amounts to surrendering Iran’s inalienable rights to enrich uranium unconditionally, under the terms of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

For both Western and Iranian proponents of the deal, however, the Geneva agreement halted a dangerous escalation in rhetoric and actions that could have easily spurred a costly regional war. It made possible high-level direct negotiations between Iran and the United States for the first time in more than three decades, creating a viable framework for meaningful discussions about Iran’s nuclear program.

Any dispassionate analysis of the Geneva agreement vindicates the proponents’ position. Even if the interim deal were devoid of any substance (which it most certainly is not), the mere fact that it inadvertently exposed the dubious, hawkish drum-beating by hardliners on all sides is an accomplishment in its own right. The resulting alignment of views between American, Iranian, Israeli, and Saudi neoconservatives is no small irony—war-mongering makes strange bed fellows.

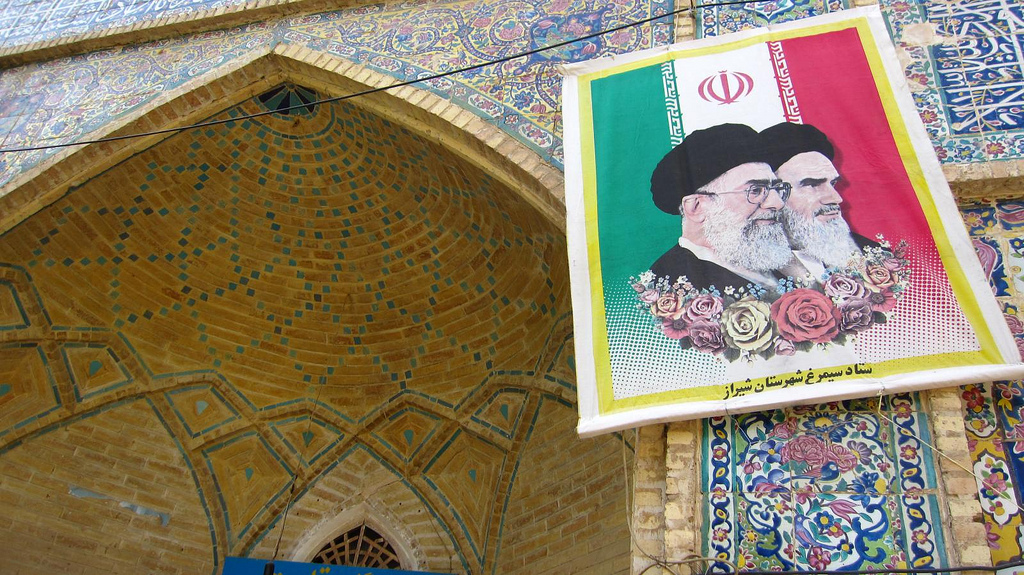

We are familiar with the domestic politics on our end of the equation, but what accounts for the shift in perspective by Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei? What compelled Khamenei to opt for “heroic flexibility” on Iran’s nuclear program after projecting a decidedly uncompromising position for nearly a decade? Was it the pain associated with the sanctions, or a broader sense that radicals within his own government needed to be reined in?

The answer to such questions holds the key to resolving the nuclear standoff with Iran; but even more significantly, it would reveal the long-term strategic objectives of the Islamic Republic.

Contrary to conventional wisdom on the interim deal, the ongoing negotiations are not only about Iran’s nuclear program or U.S.-Iranian animosity. The real underlying issue for Khamenei is the future of the Islamic Republic as a revolutionary regime. Whether by intention or sheer coincidence, Iran’s advances in nuclear technology, coupled with its regained status as a regional hegemon in the aftermath of the costly wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, have forced Western countries to take Tehran’s strategic priorities and regional aspirations seriously. Gone is the talk of “regime change” and unceasing scrutiny of Iran’s human rights record—today’s catchphrases in Washington are “constructive engagement” and “grand bargain.”

For Iran, a more accommodating West poses its own set of challenges: How do you preserve the Islamic Republic’s anti-Western revolutionary zeal in the face of gradual rapprochement with the United States? To complicate matters further, the burden of change falls squarely on the shoulders of Ayatollah Khamenei, whose arbitrary exercise of power is more often than not justified as a necessary response to the designs and machinations of “arrogant powers,” as he routinely refers to Western nations. What happens if the “arrogant powers” suddenly stop being so arrogant?

Khamenei and his supporters are unlikely to disavow the vocabulary of enmity overnight, and even its practice on the margins (say, by supporting militant groups like Hezbollah, or Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria). Similarly, their comprehensive sanctions against Iran have backed Western governments into a corner by placing the high demands made of the Islamic Republic at the mercy of domestic political forces. The continued threats of even more punitive sanctions on the Iranian economy by hawkish members of U.S. Congress, for instance, are a recurring threat to the unfolding negotiations going forward.

For now, the interim deal—taking us from full estrangement to partial stalemate in the face of formidable opposition—is no small achievement. But it is only the first act in a drama that still requires great reservoirs of courageous leadership on all sides.

Send A Letter To the Editors