For a time, most likely between the ages of 5 and 8, I floated around with a secret: a dogged yet utterly erroneous notion that my family spoke a second language—on my mother’s side at least.

The assumption arrived out of nowhere, planted itself, and for a while, took root. I let it bloom. Quietly, I kept a list in my head. My mother would refer to objects or routines by names I never heard on television nor picked up in the chatter along the breezeway at my southwest Los Angeles school. What this meant was that words took on an exotic flourish—the sink became “the zink”; the concrete traffic median we’d sometimes get marooned on crossing one of L.A.’s wide boulevards was known as the neutral ground. My mother would announce to my father that she was off to “make groceries”—and though he would just nod and turn back to the TV news, there was part of me that hoped she didn’t need the car keys, that there’d be magic: a cluster of brown shopping bags would simply appear—conjured up from thin air—on the breakfast-room table.

The assumption arrived out of nowhere, planted itself, and for a while, took root. I let it bloom. Quietly, I kept a list in my head. My mother would refer to objects or routines by names I never heard on television nor picked up in the chatter along the breezeway at my southwest Los Angeles school. What this meant was that words took on an exotic flourish—the sink became “the zink”; the concrete traffic median we’d sometimes get marooned on crossing one of L.A.’s wide boulevards was known as the neutral ground. My mother would announce to my father that she was off to “make groceries”—and though he would just nod and turn back to the TV news, there was part of me that hoped she didn’t need the car keys, that there’d be magic: a cluster of brown shopping bags would simply appear—conjured up from thin air—on the breakfast-room table.

Things were not clarified when my grandfather would make his monthly call from New Orleans, my mother’s birthplace, to attempt a conversation. Over the hiss and crackle of a long-distance connection, I’d cup the powder blue receiver tight against my ear and squeeze my eyes tight in an effort to hear him more clearly, to picture the unfamiliar arrangement of words (the ones I could pick out, anyway). But the problem wasn’t the volume or pitch of his voice, or even the ambient noise cluttering the line. It was the lacy tumble of phrases, the odd architecture of his sentences. Only a slight uplift in tone told me that whatever he had just said was a question to which I should respond.

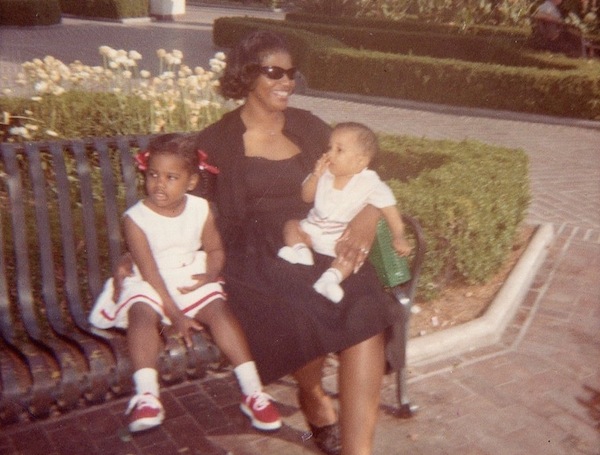

Lynell George, her mother Elodie Bowers George, and her brother Leonard George, Jr., at Union Station in Los Angeles, 1965

New Orleans, though more than 2,000 miles away from our Los Angeles home (where the Crenshaw District meets Hyde Park), was a daily part of our household for as long as I could remember. It was a guest at the dinner table; it was a bedtime story; it was the Zulu Mardi Gras coconuts on the piano; it was the special trip to the New Orleans Fish Market—past the “regular” supermarket—for proper crabs and oysters; it was the correct way to devein a shrimp; it was the Lloyd Price and Fats Domino rhythm & blues spinning round-and-round the hi-fi. Louisiana was the lagniappe—the little something extra.

Through most of my childhood, my mother kept New Orleans in plain sight, like the bouquet of fresh-cut irises on the polished dining table—living echoes of the fleur-de-lis. Though she’d been away for decades, the city wasn’t part of her past; it was as if she’d slid her finger in a book she had been reading to hold her place temporarily. She’d be back into that story in a moment—or as she’d have to admit sometimes to questioning friends, “Cher, really, it’s been more like a hot minute. But I’ll get home.”

My mother was building a future for all of us, “what was” was just as important as “what would be”—she always talked about the importance of being anchored. My dad, who was born in Pittsburgh, and grew up in Philadelphia before moving to L.A., took pride in his roots, but didn’t demonstrate it in a ritualistic way.

But New Orleans was a cardinal point in my mother’s everyday life. Her way of keeping New Orleans alive was through our daily interactions: the stories of the dust-ups her uncles (Percy, Algernon) would find themselves in, the mental map of street names she’d once lived on or near (Duplessis, Rocheblave, Cortez, Miro, St. Peter).

Food and patois invoked place, as did songs at bedtime (“Monsieur Banjo”) and, later, ghost stories about chairs rocking on their own on the porch—a whole family album of noisy, walking specters. In certain ways, I knew New Orleans before I knew Los Angeles.

Well into my teens, I spent summers there, away from the ocean air, the L.A. light, the faint outline of the San Gabriel Mountains that help define our sense of place.

In the beginning, those trips felt like a sentence—hard time. August was the swampiest month of the season. The atmosphere was a being itself. It was like walking through something solid—a door into another world. My hair would curl in ways the dry heat of L.A. didn’t allow; my arms, legs, and eyelids would populate with mosquito bites. And, slicing through midday: the out-of-nowhere lightning storms descended, dumping a deluge that would quickly turn to steam. And there was that smell—like a room closed a century—something over-ripe and sharp.

George’s grandfather, Frank Dixon Bowers, III, at Jackson Square in New Orleans, c. early 1970s

Here, without the interference of wires and time zones, I understood my grandfather fully. As well, I saw my mother become a more vivid, if vulnerable, version of herself—a daughter to her father who would never leave this place, chatting, on the narrow porch in her mother tongue. Their roots were four generations deep here in Louisiana. We settled into the little double-shotgun, painted white. A stowaway from another century, his neat narrow home was perched on a street that you could take four steps across and be on the other banquette. You lived so close to other families that everything floated into the street—intersected—music, conversation, fights, “relations.” There were few hiding places or secrets.

Like most of the other black families who lived in our L.A. neighborhood, we disappeared “elsewhere” for long pauses. Sometimes kids alone were sent for a full summer away, shipped off to relatives still residing at the starting point of their family’s Great Migration. Come fall, when we were tossed together again, I began to realize that my South was very particular, and that being of “Southern roots” was both a specific and relative thing. I heard the differences in their language, in their rituals, and most particularly in their food: I never ate chitlins or pig’s feet. My friends from other southern locales didn’t know about étouffée, beignets, or coffee with chicory (which, only on these trips, I would be treated to with a generous pour of condensed milk).

Not until my early 30s did I start to realize how much I was altered by this dual citizenship of sorts: how much my mother’s layering of stories had shaped who I am in the world—or perhaps more importantly, that I cared. A visit back to New Orleans after both my grandfather and mother were gone sharpened the feeling that I should carry these family traditions forward and fed a worry that I might not be able to.

A few months back, I was interviewed for a New York Times story about marginalia. I’d written an essay about discovering my mother’s notes and cross-outs on the pages of her old New Orleans cookbooks. She’s now been gone five years and there, in those pages, I still hear her.

As we were finishing up the conversation, the reporter asked if she could describe my mother’s voice as being “accented.” No. I answered quickly. She didn’t have an accent, “Not like my granddad.” Funny thing. I admitted, “I actually sound just like her.”

“Well you have it.” The swift confidence of her assessment disarmed me. “Not the thick accent, but the manner of speaking.” There it was: stealth but perceptible. Embedded.

Emotionally, I realize, I still commute between two homes—a physical one and a spirit one where I feel most understood. I always wear a silver fleur-de-lis, originally an emblem of the French influence on New Orleans and now a symbol of the city itself, on a chain around my neck. It rests against my throat, just at the place someone else’s Star of David or crucifix might.

Strangers glimpse it and ask: “Are you from Louisiana?” And depending on where I am situated in my head or in my heart I’ll tell them—“I’m from the other L.A.”—and not clarify, because I want to own both. The territory between those two points is my own personal neutral ground.

Send A Letter To the Editors