A group of Asian-American organizations recently held a splashy press conference in Washington to announce that they will file a federal complaint against Harvard University. Their allegation: Harvard and other Ivy League universities make admissions decisions based on racial quotas and stereotypes, in ways that effectively cap the number of Asian-American students who make it to their elite institutions.

The complaint seems plausible, and it has ignited heated conversations about Asian-Americans and affirmative action. But, as a sociologist who has researched Asian-Americans, stereotypes, and the American education system, I can tell you the allegation is simply wrong, and the conversations tired and misguided. The group making the allegations—and too many other Americans—are looking at discrimination in the wrong setting. Where Asian-Americans face the discrimination is not in schools, but in the workplace.

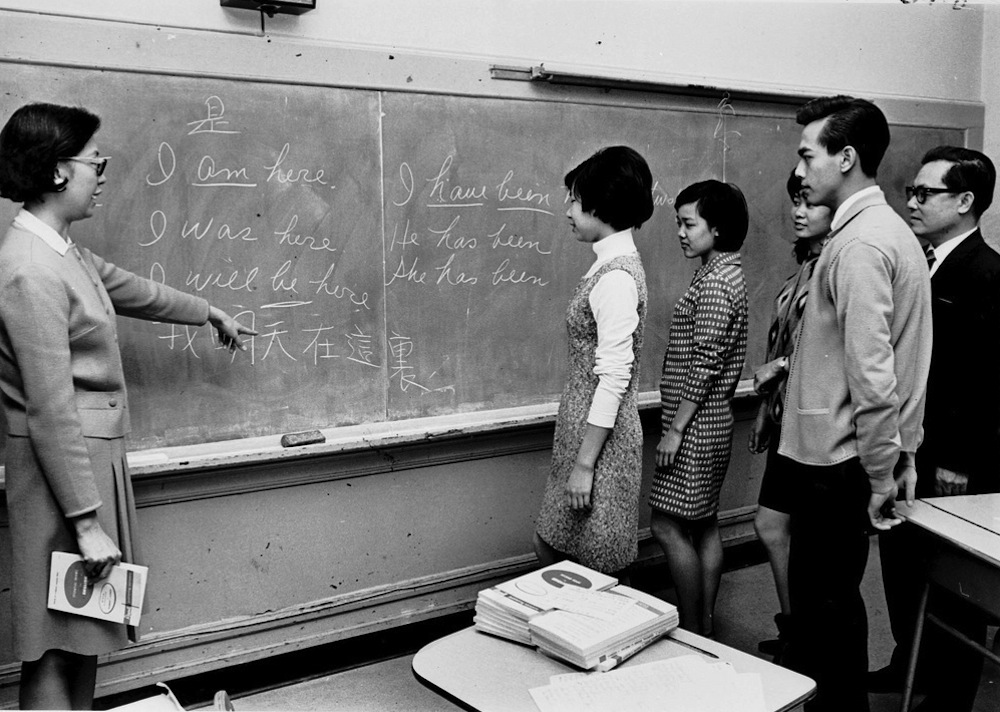

In my own research, I’ve learned about the hidden ways in which Asian-Americans actually benefit from racial stereotypes in schools. Asian-American students are positively stereotyped by teachers, guidance counselors, and school administrators as smart, high-achieving, and hard-working. The positive racial stereotypes and biases can result in what I’ve called stereotype promise—people expect the best, and that expectation can enhance students’ academic performance.

As a result, Asian-American students are more likely to be placed in more competitive academic tracks, and are more likely to be offered help with their college applications. Hence, if stereotypes and biases are operating in schools, they are typically operating to help, not hurt, Asian-American students. Of course, these positive stereotypes can be a double-edged sword, and make those who do not attain high academic outcomes feel like failures and outliers who do not meet the perceived norm for the Asian-Americans: This is the burden of the model minority trope.

Affirmative action policies do not allow institutions like Harvard to establish racial quotas, but rather give them the right to consider race as one of many factors in making their admissions decisions. Indeed, there are a number of factors that can boost an applicant’s rating, which Harvard’s Dean of Admissions William Fitzsimmons has referred to as “extracurricular distinction and personal qualities,” including whether an applicant is a legacy, an athlete, the first in his or her family to go to college, from a state from which relatively few students apply, or from an economically disadvantaged household. Elite institutions like Harvard seek to create a diverse study body along all of these dimensions, and considering race in admissions helps to achieve that.

While some Asian ethnic groups like Chinese and Koreans—who are highly-educated, on average—may not benefit from affirmative action in education, the reality is that affirmative action policies are needed for less advantaged Asian ethnic groups such as Cambodians, Laotians, and Hmong. These groups are disproportionately poor and exhibit higher high school drop-out rates than African-Americans and Latinos. Their disadvantage results in poorer test scores and grades, which would make admission into elite universities difficult if admissions were based on these indicators alone. Affirmative action policies allow universities to consider their disadvantaged status, and also consider how this would contribute to diversity on campus, where students have an opportunity to learn from one another.

Where those Asian-American students who make it through Harvard may truly find stereotypes holding them back is once they graduate and enter the workforce. While positive stereotypes may boost Asian-American students’ performance, the very same stereotypes work against them as they climb the corporate ladder and vie for leadership positions. Asian workers may be perceived as smart and hardworking, but non-Asian employers and peers also perceive them as lacking leadership skills, creativity, and managerial bravado.

A recent study of Silicon Valley’s tech industry showed that while Asian-Americans make up 27.2 percent of the professionals in tech, they comprise only 13.9 percent of executives. Even in the field of education, where Asian-Americans are overrepresented, they are severely underrepresented in leadership positions at the department and university levels. They make up less than 1 percent of corporate board members and about 2 percent of college presidents. Asian-Americans may be facing a “bamboo ceiling,” not unlike the glass ceiling that women face.

How to break down that ceiling? Affirmative action, of course.

I can personally attest to how affirmative action policies help Asian-Americans. Had it not been for the University of California President’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, which privileges postdoctoral applicants from diverse backgrounds or whose research focuses on diversity issues, I would not be a professor today at the University of California, Irvine. Despite having earned a bachelor’s and a doctoral degree from an Ivy League university, I needed the extra time and support that I received from the postdoctoral fellowship to be a competitive applicant on the academic job market. I am a proud and grateful beneficiary of affirmative action, which surprises my students, most of whom mistakenly believe that affirmative action policies benefit only African-Americans and Latinos.

Most Asian-Americans have come to appreciate affirmative action already. The vast majority of Asian-Americans (69 percent based on the National Asian American Survey) support affirmative action policies in education and the workplace, and more than 135 Asian-American organizations declared their support for affirmative action policies recently. These organizations are more likely to have been founded by U.S.-born Asians, who tend to be more supportive of affirmative action policies than Asian immigrants who are from highly-educated groups like the Chinese, Koreans, Pakistanis, and Asian Indians. U.S.-born Asians are more likely to understand the thorny history of racial groups in the United States, and are more attuned to the subtle and covert experiences of racial bias in their everyday lives.

Americans of Asian heritage are no different than other Americans in wishing to live in a country where educational and work opportunities are open to all, not just a select few. The chances of making it to Harvard, becoming a university president, or having a seat on a corporate board are already slim and unequal at the starting gate. If we chuck affirmative action policies out the window, as the Asian-American plaintiffs would like, we are only narrowing the chances even further for nearly all Americans. And Asian-Americans who complain about racial bias and discrimination in schools will find that they have shot themselves in the foot when they confront bias, discrimination, and the bamboo ceiling in the workplace.

Send A Letter To the Editors