When I first arrived in San Francisco in 1988, I often took a bus called the 22 Fillmore, which ran from Potrero Hill, made a right turn near the Castro, and out to the Tony Marina. On one end dwelled ancient socialites in little hats and on the other old longshoremen, with so much wackiness in between that the route was rightly called the “22 Fellini.” It was like the old canard about nudist camps—everyone on the bus was an equal, especially because none of us knew when the next one would arrive.

Now, San Franciscans are, on average, younger and more prosperous, and when they ride the bus they are looking at their phones, where they can track the 22 Fillmore in real time. They can also probably see a digital readout of arriving buses at a stop, or receive texts and social media updates from San Francisco’s municipal transit agency. Any traveler can also open up all sorts of other smartphone and desktop apps to navigate the system, like Google Maps, Moovit, Rover, and Routesy. These days, when you ride the bus, you ride with Big Data.

The world of apps for transit started with a great deal of promise. Evidence from Seattle suggested that merely letting riders know when the next bus would arrive could actually make people happier with their bus and more likely to take another trip. Fully integrated apps now let people plan trips that move from trains to buses and private cars or bicycles at the ends. Eventually, this data-rich universe may encourage city dwellers to give up their cars, reducing traffic congestion, pollution, and greenhouse-gas emissions. So on a recent trip back to San Francisco, I tried using some of the local apps to see how they changed my experience.

I was taking part in a big civic—and economic—experiment. Though there aren’t yet any studies showing whether apps increase transit ridership, apps themselves are much cheaper than buses and trains and tracks and drivers. When apps are used to pay for fares (as they are in San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Dallas, among other cities) they shift the cost of fare machines from the transit company to the riders. These complex changes in investment, risk, and time will continue as 10 percent of the world moves into cities in the next 15 years, and as self-driving cars start to prowl the streets. Uber has raised $15 billion in venture capital to move into the space between public and private transit around the world. And in the long run, these changes could create a richer transit universe for everyone, or a poorer one accessible mainly to the rich.

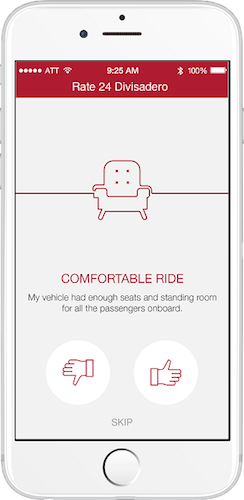

Munimobile’s ‘Rate My Ride’ feature.

I first pulled out my $29 Android smartphone along the T line on Third Street. The app produced by MUNI, the local transit system, required that I give it my email and create a password. Even though I’d given up my anonymity, the app didn’t seem to know exactly where I was. So I walked towards where I thought the stop was, only to find a digital readout saying that the next trains were coming in 12 and 14 minutes. Aha! Poorly spaced trains are a problem no app can fix.

That problem is important. As nice as information is, what riders really want is service. Candace Brakewood, assistant professor of engineering at CUNY, did research across three boroughs of New York from 2011 through 2013 and found that lines giving riders accurate information on arrival times increased ridership by as much as 2 percent on an average day. “When you aggregate that across NYC it’s very significant,” she told me. But she also looked at the impact of the weather, the economy, service changes, and multiple other factors and found what really increased ridership was more frequent buses and shorter trip times. This is hardly a Moneyball-type revelation from the crunching of Big Data. “Yeah. Commonsense,” Breakwood said.

Once the T arrived it was pleasantly crowded, with a mix of ages and ethnicities, and the ride on the tracks was mostly smooth. Some older black folks in suits were still enjoying Juneteenth, singing a song from another era. A younger woman with pink hair was drinking from a can. And a guy with long arms was waving them exuberantly as he talked on the phone. As we rolled past the ballpark it occurred to me that the city had spent a lot of money establishing itself as a party town, and the crowd of us here on the train was a truer reflection of that happy civic spirit—the 22 Fellini of it all—than many of the recent expensive infrastructure investments. An Asian grandmother with two little children boarded. The train lurched, they all nearly fell over, and then started giggling. The arm-waving man shot out of his seat and offered it to them. Our civic project rolled along.

What does this all have to do with apps? SF MUNI plans to release a new app component this summer that allows passengers to comment on the etiquette of fellow riders, along with train cleanliness, trip time, crowding, and comfort. Rate My Ride encourages readers to swipe right or left—in homage to Tinder, I guess. MUNI employees will monitor these swipes and “target specific train routes and bus lines” for improvements, according to Paul Rose, spokesperson for MUNI. “It’s one way to make it easier for riders to let us know how we can improve their transportation experience and further engage our riders,” he explained.

I tried to imagine myself swiping my fellow passengers on my phone, but to me the beauty of the bus is enjoying the way everyone gets along and ignoring the ways that we don’t. The singing was nice. I had no problem with a quiet drink. The seat hog at 23rd Street was an angel by Fourth and King.

So how do people rate other passengers’ etiquette, and how should the transit agency react to them? “There’s an idea that because apps are software they’re non-discriminatory and egalitarian. And if you put them in the hands of people they’ll naturally lead to good,” said David King, an assistant professor of urban planning at Arizona State University. But, King worries, it’s likely that the app will be hijacked by racist, sexist, or anti-poor opinions—just like platforms including Nextdoor.com, AirBnB, and Microsoft’s chatbot Tay, which became a raving fountain of hate-talk within hours.

What’s more, in the world of public services, some voices—particularly those perceived as white and middle class—are more powerful than others, attracting more sympathetic policing, more funding for potholes, more municipal love. MUNI’s app will be available only in English to start, even though bus announcements are often in English, Spanish, and Chinese. The agency says they expect to release the app in other languages. It could be harmful to only collect complaints from English speakers, but wouldn’t the very idea of the city itself be challenged if we all secretly complain about each other in multiple languages?

Perhaps more important, if the core issue with increasing transit ridership is train frequency and travel time, should MUNI spend its precious resources tracking and responding to passenger etiquette? Transit needs to be more rider-focused, but the meaningful difference comes when public transit is more plentiful and convenient. And citizens change that through engagement in the budgeting and planning process, not by writing bad Yelp reviews. At the moment, apps offer riders an illusion of control. In the long push-pull over transit service, though, the apps aren’t automatically a force for good.

On a trip back from the East Bay, I used Moovit to calculate my route. Taking BART and bus, the app said, would take 86 minutes, while an ad offered a button to call an Uber that would cost $21 and take 56 minutes. As it turned out, the app was wrong, and between BART and the 5 Fulton bus I got back home in 72 minutes for about $6. And of course, I got the whole Fellini too.

Send A Letter To the Editors