I still remember them at the dining table after dinner each night in our Honolulu home. Three elegant sisters, styled out of Vogue magazine, their jet black hair in neat chignons and pixie haircuts, each savoring a cigarette and lingering over a glass of bourbon. Their laughter rang, but did not always conceal the dark ironies and black humor of memories they laced together of our Japanese-American Hawaii family torn apart by war.

I still remember them at the dining table after dinner each night in our Honolulu home. Three elegant sisters, styled out of Vogue magazine, their jet black hair in neat chignons and pixie haircuts, each savoring a cigarette and lingering over a glass of bourbon. Their laughter rang, but did not always conceal the dark ironies and black humor of memories they laced together of our Japanese-American Hawaii family torn apart by war.

“Do you remember when we left Hawaii after dad died and moved to the family home in Kyoto?” my youngest aunt would say, referring to the brusque relocation of the three sisters and their mother immediately after their father died of a massive stroke four years before the war began.

They thought they were going home, but found themselves caught between two conflicting worlds. “Japanese soldiers would harass us at every train stop,” my aunt recalled, “taking away our rations because we were American, so we discovered how good the roots of weeds and grasshoppers were when we cooked them in shoyu and oil.”

“Yes, but the soldiers didn’t last long,” my mother would correct her, “all of them were sent to war—even the old men and young boys—except for those annoying intelligence officers who kept interrogating us. Food was gone, too. That’s why mother went to the family temple in Fukui where there was rice.”

“You two were so selfish then,” my oldest aunt would tell her sisters, “but you were young. After our sad dinners, I’d be upstairs and you thought I was asleep. You’d hide a small piece of mochi or nori and you’d grill it over the charcoal that kept the house warm. You didn’t realize the smell of any food woke the rest of us up, and we would hear you trying to be so sneaky … bad girls!” This would send them into gales of laughter.

The stories would cycle again and again, I would sit with my mom and her sisters at the light green Formica dining table, surrounded by banana trees and their lilting voices and laughter, feeling privileged to be a part of their closed group, rapt at each retelling. I’d use each of these times with my aunts and mother, by then in their 40s, to color a fuller picture of the Imamura family history—of lives torn apart and torn between homes, between identities, and between the two sides of the vast Pacific. Their oldest brother, a Buddhist bishop sent to California to start a temple and an institute for Buddhist Studies, would later help communities of other internees resettle into a country that had distrusted them, imprisoned them, and allowed their businesses and farms to be taken; the second brother, a Harvard graduate, married into a wealthy Japanese family (which meant taking their name) and helped lead their kimono factories before working as an interpreter in a U.S. consulate after the war. Their youngest brother, a Keio University graduate whose dream job as a political reporter for the Mainichi News transformed into an embedded war correspondent with the Imperial Japanese Army in Burma, Thailand, and Malaysia, would later focus on U.S.-Japan relations in his reporting and would build ties between the countries through his support of professional baseball.

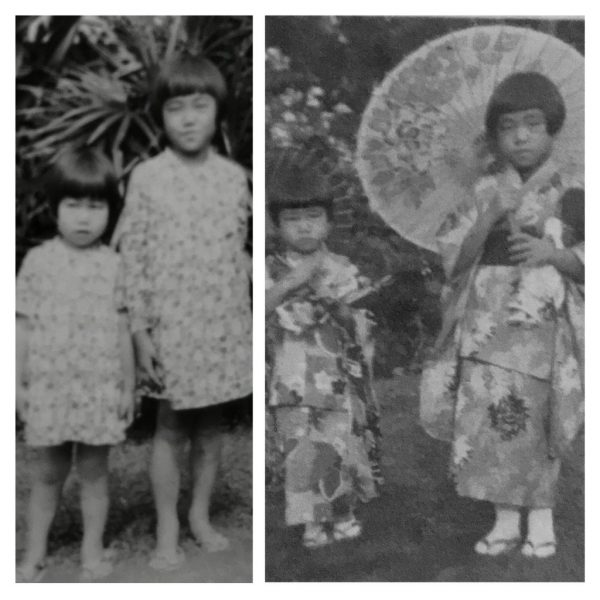

Author’s mom and younger aunt who identified as Hawaii-born Japanese Americans. Photo circa 1930s.

The three sisters, for their part, worked in the English-language section of a women’s university library, keeping their bilingual skills up so that they would be ready to act as translators and coordinators for the Occupation of Japan, accompanying rising Japanese political leaders to the U.S. to be trained in the ways of democracy. Across their different careers, the Imamura siblings were all encouraged by their father to be the Bridge People: connectors fluent in the history, language, culture, and values of both nations, whose skills and perspectives made their roles connecting Japanese and American worlds both inescapable and honorable.

Though the laughter of my mom and aunts’ after-dinner conversations fills my memory, I remember just as well when they’d go quiet.

A hush would fall as my mom recounted how, as a high school student in Kyoto, she sat in her university class listening to the school intercom announcement of the Japanese offensive on a U.S. Pacific naval base.

“When I heard they had attacked Pearl Harbor,” she’d say, “I started to cry because that was my home. Through my tears I felt all of these eyes slowly turn towards me. I was American. They all suddenly realized it.”

The sisters’ cadence would also slow as they spoke of their eldest brother, Kanmo, painting the picture of a scholarly, quiet, and handsome man—the 18th generation member of our family to become a Buddhist bishop. His life, they would reflect, was the hardest from the beginning. Kanmo was born in Hawaii, but sent back to Japan when he was four years old to be raised as a bishop. His childhood was a lonely life at the temple without the family: tutored by priests and a step-grandmother who was distant and cold. He would tell me, years later, how he would walk alone between the temple and the house in the winter, the Sea of Japan’s cold air blowing through his priestly robes, wondering why he couldn’t be in Hawaii with his family. He would return to Hawaii to be the priest at the largest plantation temple in Wahiawa, and would realize his father’s dream of growing a temple and study center in California to support the Japanese community there.

Just as Kanmo started to expand the temple programs, the war began. Soon he found himself supporting Japanese-American families in the internment camps, helping those forced away from their homes over unfounded allegations of conflicting allegiances (especially ironic for those who had sons proving their loyalty with blood and body in 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe, a battalion where young Japanese-Americans prominently served). Three of my uncle’s children would be born in the sand-filled winds of the Gila River internment camp. At the end of the war, he saw his mission as providing shelter, food, dignity, and spiritual support to those released from the camps, often with nothing more than a train ticket and $30 in their pocket, to reclaim the businesses and farms taken from them. He would spend the rest of his life building interfaith study centers and programs for the disenfranchised, and returned to his birthplace to become the Bishop of the Headquarters of the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temples of Hawaii.

Author’s oldest uncle with his wife and first child at the Gila River Internment Camp.

The sisters spoke with reverence for their middle brother, Shinshi, too. The hard-working Harvard graduate, had dreams of working for the American government. His hopes were dashed—as fate would have it, he was the only of the siblings not born in Hawaii, and his Japanese birth disqualified him from service. His ambition took him elsewhere though— Shinshi would become the head of General Motors in Japan, another form of bridge-building.

The youngest brother, Tokushi, a basketball prodigy in his school days in Hawaii, had an improbable gig straight out of college: he was an American reporter embedded with the Japanese Imperial Army in Burma and Shanghai. Tokushi would go on to become the political editor for the Tokyo-based Mainichi Shimbun, one of the top newspapers in the country. But he didn’t forget his American roots, and spent his free time doing such things as recruiting Japanese-American baseball stars like Wally Yonamine for Japanese teams or coordinating a trip for Helen Keller, the first U.S. Goodwill Ambassador sent to Japan after the war. The bilingual jokester also managed to stay friends with his McKinley High School pals in Hawaii, and somehow remained the quintessential “local boy” among them, despite the miles that separated them. I still remember the bright energy that would fill the room whenever my aunts and mother spoke of him.

I knew the night was winding down when the sisters would turn to talk of their mother, a Buddhist bishop’s wife who herself came from a long line of bishops and abbots, poets and publishers, and military rulers from a Shogunate that rose in the 14th century and waned by the 17th.

“Do you remember her practicing for the citizenship test when we were growing up in Hawaii, memorizing the entire Emancipation Proclamation?” my oldest aunt would start, “It was so funny to hear her pronounce ‘Emancipation Proclamation’ and to hear her recite ‘…all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free.’”

“Her favorite movie scene was in Gone With The Wind,” my oldest aunt would recount, “and Scarlett’s defiance when she says, “As God as my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.”

In Japan at the end of the war but desperate to return to Hawaii with her children, grandmother Kiyo Imamura made her way back to Hawaii—“the birthplace of the ‘Bridge People,’” as she called it—to end her journey.

My family is not alone, of course. All second-generation Americans reconcile the norms and values of their family’s culture and of American culture, to the enhancement of each one. Such bridge-building replenishes and enriches our national fabric, reminding us of the universal relevance of our core values and adding texture to the American story. In Hawaii, where the host culture of Native Hawaiians accepted waves of immigrants through interracial marriage and linguistic and religious tolerance, cultural bridge-building is practically the state’s mission statement. Hawaii may seem far away from the mainland, but it couldn’t be closer to the American understanding of how diversity creates strength and unity.

Send A Letter To the Editors