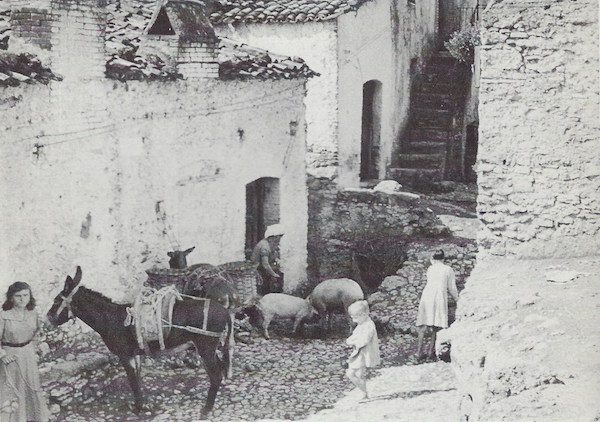

More than 60 years ago, an American family arrived in a seemingly idyllic town in Southern Italy. Stone buildings resembled “a white beehive against the top of a mountain.” Donkeys and pigs idled in the ancient, winding streets. A town crier tooting a brass horn announced “fish for sale in the piazza at 100 lire per kilo.” There were two churches, two bars, and a movie theater. Shops offered locally made shoes and olive oil, and locally-sourced meat. Nearly everyone farmed and tended animals and knew one another, at least by name or reputation.

Yet Chiaromonte’s 3,400 residents were anything but content. They were crushingly poor and simmered with resentment. Why? In great part, as the Americans learned during their stay, because they were too family-focused.

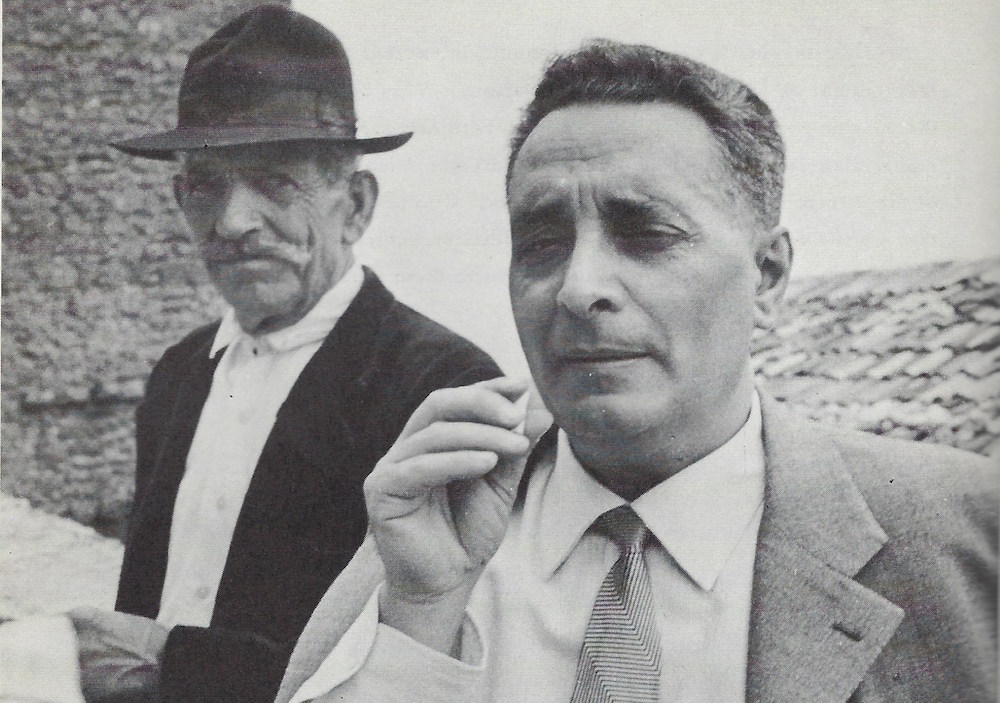

Political scientist Edward C. Banfield went to Italy in 1954 to better understand poverty. Researchers then tended to assume people were poor due to lack of education or because they were victimized by the government or capitalism. Banfield himself had been a reporter and had traveled across the United States during the Great Depression, so he knew the reality was more complex. In order to understand why people are as they are and do what they do, Banfield believed one needed to learn how they viewed the world and their place within it.

This may sound self-evident, but it cut against the academic grain of the day. The University of Chicago, where Banfield earned his doctorate and had a teaching appointment, was known for its shoe-leather sociological research. Its Prof. William Foote Whyte, for example, wrote Street Corner Society in 1943 after four years studying a slum in Boston’s North End.

In 1956, Banfield and his wife Laura (who spoke Italian) spent nine months in Chiaromonte and interviewed dozens of residents. They pored over census data and official records, enlisted some residents to keep diaries, and conducted psychological surveys on others. Two years later, The Moral Basis of a Backward Society described what they had found and concluded that Chiaromonte’s poverty and grim melancholia (la miseria) were rooted in its people’s “amoral familism.”

The adults’ core attitude was that one must “maximize the short-run advantage of the nuclear family,” and “assume that all others will do likewise.” This might not seem like a bad thing—doing good for one’s own family is universally lauded as moral behavior. But taken to an extreme, a focus on the family can be destructive. Socioeconomic progress demands that individuals cooperate with one another, and work for the common good.

There was very little of that in Chiaromonte. Banfield found no organized voluntary charities, just an order of nuns—brought in from outside the town—struggling “to maintain an orphanage for little girls in the remains of an ancient monastery.” The townsfolk, he found, “contribute nothing to the support of it, although the children come from local families. The monastery is crumbling, but none of the many half-employed stonemasons has ever given a day’s work to its repair. There is not enough food for the children, but no peasant or landed proprietor has ever given a young pig to the orphanage.”

The priests in the town’s two churches feuded, and Sunday worshippers seldom contributed to the collection plate. The town’s doctor didn’t modernize his medical equipment because he saw no personal advantage in it. Patients could take it or leave it. Italian law required all towns to provide schooling to at least age 14. Chiaromonte’s school stopped at fifth grade, and the teachers’ attendance was erratic, their attitude toward their pupils defined by indifference.

Amoral familism bedeviled local politics. Residents assumed anyone engaged in civic life was secretly out for personal gain. Few residents participated in politics or public affairs, and most dismissed government as hopelessly corrupt. When a citizen attempted to organize a political party, the townspeople balked at paying even paltry membership dues. The town’s council was riven by factions, and seldom able to work with the mayor (who was unpaid) to get anything done. Those who participated in politics frequently switched their party identification based on opportunism, not ideology. The secretary of the monarchist party became a communist, then declared himself a monarchist again. Seeing why was not difficult: voters believed politicians were cheating them and thus voted against whomever was in power.

Amoral familism also impoverished families. By tradition, a son was entitled to inherit a portion of land from his father upon marriage. The obvious result was smaller and smaller parcels of land, which were increasingly impossible to farm for profit. The son of an artisan was expected to be an artisan—never mind whether the town economy demanded a cobbler or blacksmith. From the cradle, the family socialized children—not infrequently through beatings—to follow the old ways, stay close to home, and distrust others.

Chiaromonte in 1954-1955.

Collectively, Chiaromonte’s residents all wanted more money, and each was jealous of any other who had more lire or nicer stuff. But they rarely sought to earn more by producing more or better. Banfield’s research revealed astonishingly low levels of individual agency. Unlike the family-focused southern Italian mafia (Ndrangheta), Chiaromontians were too cynical to form criminal enterprises. Crime was rare and usually petty in the town. Material success was attributed to personal corruption or luck, which might be reversed by bad luck. With everyone out for his own and on the take, the system by definition was rigged. Why try?

The Moral Basis of a Backward Society was a watershed in poverty studies, one still read in college classes today. It showed the importance of culture to socioeconomic flourishing. “People live and think in very different ways,” Banfield wrote, “And some of these ways are radically inconsistent with the requirements of formal organization.”

This was not “blaming the victim.” In the case of Chiaromonte, Banfield hypothesized amoral familism was exacerbated by factors outside the average citizen’s control. The town’s physical isolation, to cite just one factor, meant that citizens could little imagine their living other than as they did.

Some scholars criticized Banfield for overstating the power of values on behavior. They pointed to root causes. Material scarcity tends make individuals more anxious and distrustful of others’ intentions. And the larger provincial government had significant authority over Chiaromonte’s affairs, which exacerbated the political haplessness.

Banfield died in 1999, but the book continues to attract readers because its portrait of poverty is heart-aching and—to this day—recognizable. Like J.D. Vance’s recent bestselling memoir of Appalachian life, Hillbilly Elegy, Banfield’s Moral Basis shows that families can be a wellspring for poverty and misery, and that the root causes are a complicated blend that can be difficult to overcome.

Send A Letter To the Editors