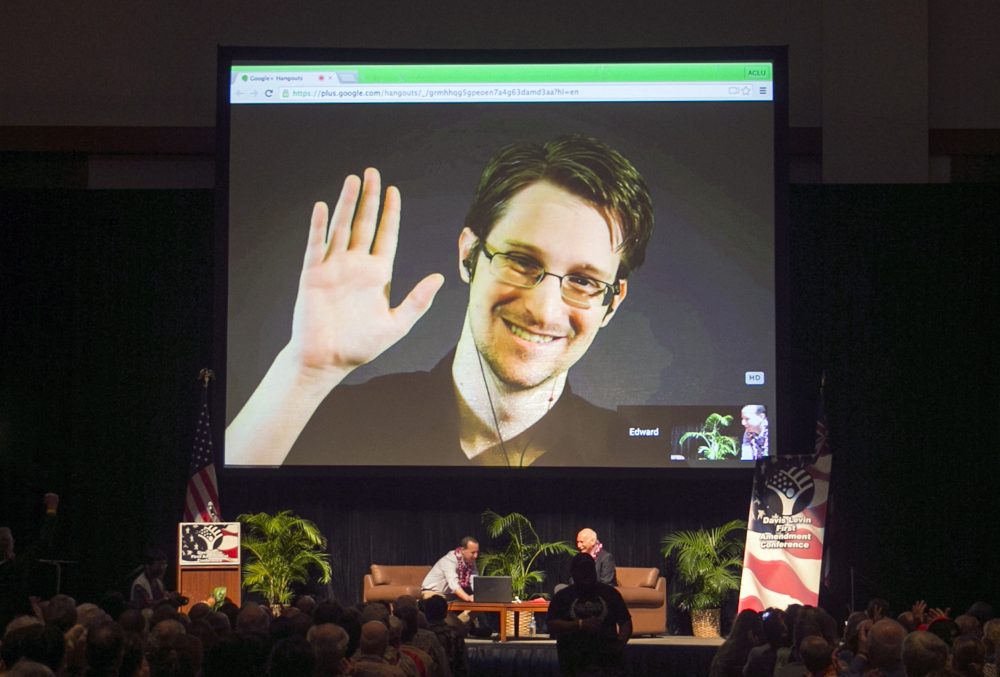

Edward Snowden appears via video feed from Moscow for a meeting of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in Hawaii, Feb. 2015. Photo by Marco Garcia/Associated Press.

Michael Greenberger is a professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law and the founder and director of the University of Maryland Center for Health and Homeland Security. The following is an edited version of a phone interview with him about data collection in the age of cyberwarfare.

When you’re talking about information that can be used, or useful, in conducting cyberwarfare, that type of data is different from the conventional identification data, which when released is an invasion of a person’s privacy, or could be used in a fraudulent manner. The missing cyberwarfare data is the data of companies like utilities, hospitals, ports, and other sorts of critical infrastructure.

The most feared and plausible cyberwarfare scenario is the crippling of the nation’s electric grid, which is the basis for the way we live our lives every day, especially insofar as it is the basis for providing critical healthcare needs of patients in medical facilities. About 85 percent of our vital national infrastructure—dams, highways, tunnels, bridges, electrical grid, sewers—is owned privately.

So any attempt to mandate the provision of that data, either to the United States government to develop counter-measures to cyberwarfare, or even to states and localities, has been strenuously resisted by the private sector. It has been resisted both as a knowing obstacle that is being set up to protect things like trade secrets and intellectual property; and it’s being resisted in an unknowing way, a knee-jerk adverse reaction to turning over any private commercial data to government institutions.

The government’s inability to access private sector data is probably the most fundamental weakness of our ability to fend off cyberwarfare attacks. The methodology that is in place now is, at best, based on incentive-driven cyber regulation, which tries to make it attractive to private organizations to turn data over to allow that data to be protected. However, volunteerism clearly is not working here, and it is therefore not enough to set up a defense to a full-scale, damaging infrastructure cyberattack.

Protecting the privacy of individual U.S. citizen data, where the government wants to collect mass amounts of private information, raises different kinds of issues. At the University of Maryland Carey Law School, I taught a class on “National Secrets, Foreign Intelligence and Privacy.” That entire course was driven by the Edward Snowden security leaks in June of 2013. Snowden demonstrated that there were various avenues the United States government was using to access private information of United States citizens.

The two central legal authorities that the United States was relying on were Section 215 of the Patriotic Act and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Amendments of 2008. Nobody outside of the federal government—and I would say most of the federal government itself—understood that these kind of surveillance activities were being undertaken.

Section 215 was the vehicle through which the National Security Agency vacuumed up so-called metadata, which is information about who a citizen calls. The data shows both the phone number of the arranger of the call, and the number of the person to whom the arranger places his call, as well as the amount of time that the call lasts.

It is not a content-driven, wiretapping surveillance—in other words, you do not know the substance or content of the call. But an outsider can tell a lot about somebody’s private life by knowing who they call on a regular basis and how long that call lasts. Knowledge of frequent calls to an HIV/AIDS advice line, Planned Parenthood, or a psychiatrist, tells the reviewer of this data important information that the caller would otherwise clearly want to be private.

This collection of metadata was further aggravated by the fact that when the metadata was accessed by the National Security Agency, if it dipped into the metadata, it could not only look at the telephone traffic between one caller and another caller, but it could search “three hops” of the data.

The first hop is “A calls B,” and the NSA could get that metadata; then the NSA could get the metadata of everybody that B calls. That’s hop #2. Then hop #3 is the metadata of everybody receiving calls from B. Therefore, with three hops you have a spider web of the metadata of hundreds of thousands of calls. When the program was made public in June of 2013 by the Snowden leaks, President Obama pledged soon thereafter: “We’re only going to collect two hops, not three hops.”

Then the next question becomes: How does the NSA access the details of the metadata it has collected? Originally, experienced intelligence officers supervised requests to access the specifics of the metadata. That was considered quite troublesome legally, because one basic tenet of a constitutional search is that a warrant is obtained from an independent court. By having intelligence officers decide whether the metadata could be searched, that tenet was violated.

One of the first things President Obama did in January 2014, besides eliminating three “hops,” was to impose the requirement that if the metadata was to be searched, the NSA, through the Justice Department, had to get a foreign intelligence surveillance warrant from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court showing that there was probable cause that searching the metadata would concern an agent of a foreign power.

Even with President Obama’s adjustments, Section 215 was criticized broadly, both from the left by civil libertarians and from the right by libertarians.

The USA Freedom Act in 2015 repealed Section 215. However, that statute required phone service providers to hold onto their metadata records for a longer period of time, and if the NSA needed access to that metadata, it could go to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to obtain a warrant to examine the metadata if it showed that there was reasonable, articulable suspicion (“RAS”) that the metadata would lead to, inter alia, terrorist activity. Of course, showing RAS is, in legal terms, not “probable cause” of criminal activity, the classic threshold for a lawful search and seizure under the Fourth Amendment. At some point, therefore, the constitutionality of this new metadata provision may be challenged.

Section 215 was the legal basis of the first of the two legs of the surveillance revealed by the Snowden leaks. The other is based on Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Amendments of 2008. Section 702 is driven by the fact that the target of the requested surveillance is reasonably believed to be outside the United States and is not a U.S. citizen, circumstances under which the Fourth Amendment would not apply.

But, in operation, Section 702 surveillance need only look to whether the communication at any time left the United States. Any email that at any time is routed outside our country—as many emails are—is subject to Section 702 surveillance. So that raises a very deep concern, because domestic emails are therefore subject to an NSA Section 702 search.

Our government is always quick to say: “We do not surveil United States citizens and only do so with a warrant.” Well, the 702 is not a warrant-driven mechanism as a predicate to the search. (The government needs to get FISA court clearance on a yearly basis for the methodology of 702 searches, but it is not required to get a warrant on a case-by-case basis.)

The NSA and the Justice Department are also quick to say that if, through Section 702 surveillance, they pick up anything that is entirely domestic, the government “minimizes” the search, or does not allow it into the intelligence inventory. However, the 702 exceptions to minimization are so broad that they swallow up the entire concept of minimization. The 702 statutory authority is set to expire later this year, and there is going to be a major debate over whether it should be extended. Section 702 has many supporters.

The Supreme Court has not ruled definitively on these surveillance issues. Even among the present eight Supreme Court justices, there is a likely majority who have signaled their doubts about surveillance that does not strictly follow Fourth Amendment “probable cause” jurisprudence. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, before his passing, was a strict enforcer of classic Fourth Amendment search and seizure doctrine. Moreover, there is evidence that Judge Gorsuch, if confirmed, will follow Scalia’s lead in this regard.

To date, the failure of challenges to these kinds of surveillances is the inability to demonstrate in court “standing” (or precise injury from the surveillance). The one Section 702 case to reach the Supreme Court in 2013 foundered on the inability of the plaintiffs to show with certitude that their communications had been read or heard. However, standing will doubtless be established in a case where evidence obtained under Section 702 is used to convict a criminal defendant. The defendant will have likely failed to suppress introduction of the evidence on grounds that it was obtained without a showing of probable cause. That criminal defendant will doubtless have standing and, if the case reaches the Supreme Court, that court will likely be able to resolve these issues on the merits.

In the end, one of the biggest cybersecurity problems is that the U.S. military-intelligence complex has far too easy access to private information that can be damaging to oneself, information that we reasonably expect to be kept private, and not put into the hands of the government without some showing that it’s directly related to a critical national need. The government has just too-ready access to far too much of everyone’s private information, and that access can be gotten without demonstrating to an independent court that there is a strong national need.

Another major cyber problem is that too many U.S. commercial interests are not using best cyber practices, best cyber technology, to protect sensitive data that, if stolen, enables crippling cyberwarfare against the United States. I do not think that failure has been given a serious enough concern. So losing your credit card information, your passport information, and other forms of privacy happens too easily. This is troublesome and worrying. But it is not the clear and present danger to our collective security of having our infrastructure data hacked and having a broad-based infrastructure break down.

The attempt to minimize the government’s access to personal private information is not a partisan issue. Libertarians on the right and civil libertarians on the left feel strongly that the government’s ability to invade privacy must be limited. However, it is hand-to-hand combat in Washington on these issues, and should there be another devastating terror attack, I think the scales will tip to the side of the government being able to collect whatever it wants, whenever it wants it.

Send A Letter To the Editors