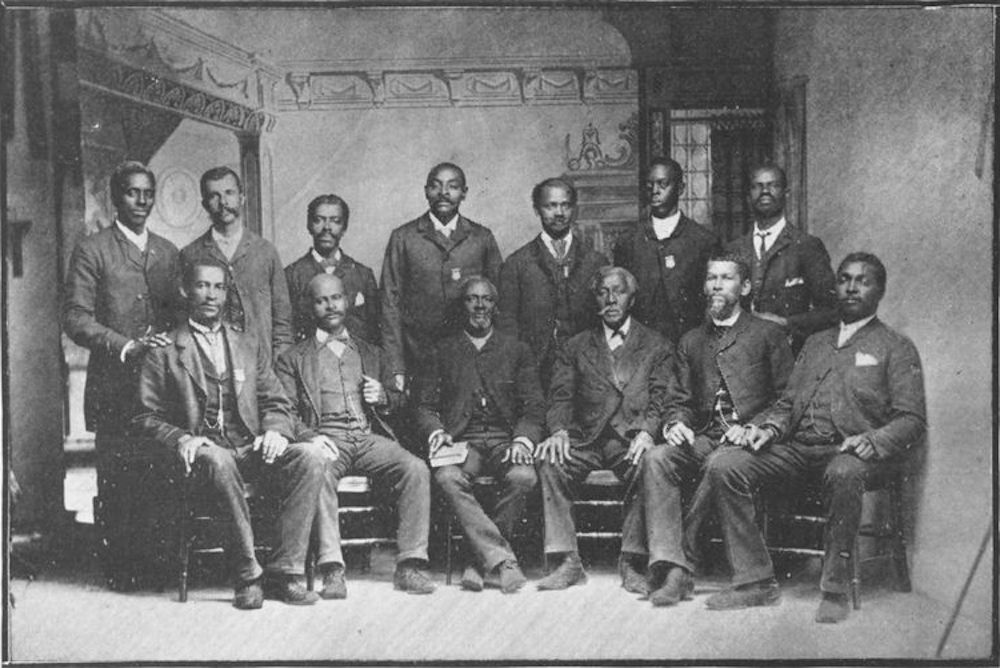

Church deacons, Savannah, Georgia, 1888. For many slaves in the American South, the African American church was not only a house of worship but a schoolroom for acquiring literacy. After the Civil War, freed slaves themselves took the initiative to push education beyond religious instruction. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The focus of my research and writing is women’s involvement in higher education, especially women from the Pentecostal and Holiness faith traditions. While conducting research on African American female seminaries, I found myself reaching back to a very rich yet little-known history of educational efforts by African Americans both during and after slavery. The narratives of those days should remind us just how stubborn and enduring the hunger for education has been in American life.

In the United States, slave masters were intent on keeping their slaves illiterate. Two events drove Southerners to discourage literacy. In the Stono Rebellion of 1739, more than 20 whites were killed by slaves attempting to escape to Florida. In 1842, the revolt led by Nat Turner in Southampton County, Virginia, cost the lives of 55 to 65 whites and more than 100 slaves. Each event led to new restrictions, in the form of anti-literacy laws and punishments for slaves who tried to learn to read and write.

The objections to slave literacy were threefold: 1) Slaves did not have the mental capacity for education and would only become confused; 2) Slaves might learn to forge passes to non-slave states; and, 3) Insurrection and rebellion might result from slaves reading abolitionist writings.

But some slaves found ways around prejudice and law to satisfy their hunger for knowledge. Their main antebellum sourcebook for literacy was the Bible.

Some masters permitted it, because they saw the Bible as teaching slaves their “divine” role as servants. Beverly Jones, a former slave in Virginia, would write: “Always took his text from Ephesians, the white preacher did, the part what said, ‘Obey your masters, be [a] good servant’ … They always tell the slaves dat ef he be good, an’ worked hard fo’ his master, dat he would go to heaven, an’ der he gonna live a life of ease. They ain’ never tell he gonna be free in Heaven. You see, they didn’ want slaves to start thinkin’ ‘bout freedom, even in Heaven.”

The Second Great Awakening (1790-1840) changed the educational calculus, by putting at the forefront the belief that all men and women from every race were in need of salvation, and that all redeemed individuals were to be “useful” in God’s kingdom. The efforts to reach African American slaves for Jesus resulted in the “planation missions” movement of the 1830s and 1840s. African Americans who embraced Christianity became not only church members but also preachers and ministers.

Plantation missions were part of a greater reform movement to bring about holiness to the whole nation, including to the Negro slave. To accomplish this, leaders of this movement had to demonstrate to the plantation owners that its religious efforts were not antithetical to slavery. Additionally, there was resistance from Southerners because they believed that African Americans didn’t have the capacity for religious experience.

Despite Southern resistance, the efforts of plantation missions were fruitful and many slaves became Christians. A multi-part process of religious instruction unfolded. First came regular sermons geared toward the perceived level of the slaves’ mental capacity. That might lead to a weekly lecture which the master and his family were encouraged to attend in order to provide a good example for his slaves. After that, Sabbath schools were established, and instruction at these school was expressly oral (and not written) “religion without letters” utilizing a question-and-answer method from printed catechisms, homilies and visual aids to achieve learning. Once schooled in Christianity, slave converts participated in regular gatherings at times and places approved by the plantation owner.

That was often as far as things went—until the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent end of the Civil War. In post-bellum Southern states, initiatives were carried out to educate freed slaves in subjects beyond religion. The foundation for these efforts came from the freed slaves themselves.

According to James Anderson, author of The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, “Former slaves were the first among native southerners to depart from the planters’ ideology of education and society, and campaign for universal, state-sponsored public education. In their movement for universal schooling the ex-slaves welcomed and actively pursued the aid of Republican politicians, the Freedman’s Bureau, northern missionary societies, and the Union Army.” Not only did African Americans improve their own educational opportunities, but they also helped improve education for whites by challenging the plantation owners’ educational paradigm that schooling happened in the home, and not in public schools.

Religion retained a powerful, if different, role in education after the war. As African Americans emerged from slavery to freedom, churches became central to their communal life and a foundation for many of self-improvement initiatives in education. The church’s ability to sustain the infrastructure of an informed society—including numerous newspapers, schools, social welfare services, jobs, and recreational facilities—mitigated the dominant society’s denial of these resources to the black communities.

As Northern missionary societies and the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freeman and Abandoned Lands (Freedmen’s Board) entered the South in the post-bellum era to educate African Americans, they found that they would be building on educational efforts already established by slaves and free blacks. White teachers, mainly from the Northeast, joined a cadre of African Americans teachers.

One of the important educational innovations in the immediate post-bellum era was the academy—primarily parochial day or boarding schools where the curricular focus was on reading, writing, and mathematics (although courses in cooking, sewing, and domestic arts were also offered.) When these schools were first started, the hope was that students would gain basic literacy so they could read the Bible, complete basic math computations, and understand labor contracts. Instead, a classical liberal arts curriculum was brought to the school by white teachers, many of whom had gained experience in New England boarding schools, and then taught by African-American teachers as they took over instruction. Practical courses in industrial arts were added to the curriculum, although the emphasis was on Latin, algebra, English literature, and foreign languages such as Greek, French, and German.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown, a self-proclaimed disciple of Booker T. Washington, founded Palmer Memorial Institute, but steadfastly resisted efforts to make industrial education an emphasis at her school. Instead, she utilized a college preparatory approach in which her students studied Latin, French, English, algebra, geometry, and science. To balance out the students’ educational experience, students took courses in agriculture, home economics and industrial education, and helped raise food for the school by working on a 120-acre farm. Brown’s school was representative of the pedagogical tension experienced by many academies.

Henry Lyman Morehouse coined the term “Talented Tenth” (popularized by W.E.B. Du Bois) to make the case that developing an African American elite was essential for the advancement of all Blacks. This concept had appeal for both African Americans and Northern missionary groups, especially the American Baptist Home Missions Society (ABHMS). For African Americans the concept of the “Talented Tenth” represented the hope of gaining respectability in American society. For many Whites, the “Talented Tenth” represented a buffer group to negotiate with the “field Negroes” revolt in the post-bellum era.

For all the devotion to education in this era, the schools developed by and for African Americans did not produce a level of property ownership and economic self-sufficiency among its graduates that were among the primary goals of these schools. Education accomplished much, but it was no match for the racist structures of the society, particularly after the end of Reconstruction.

However, this continual thirst for education among African Americans and their continued efforts to achieve it resulted in many institutions of higher education that continue to make significant contributions in the world of academia and the broader American society. Among these were Spelman University—which began as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary in the basement of the church.

Send A Letter To the Editors