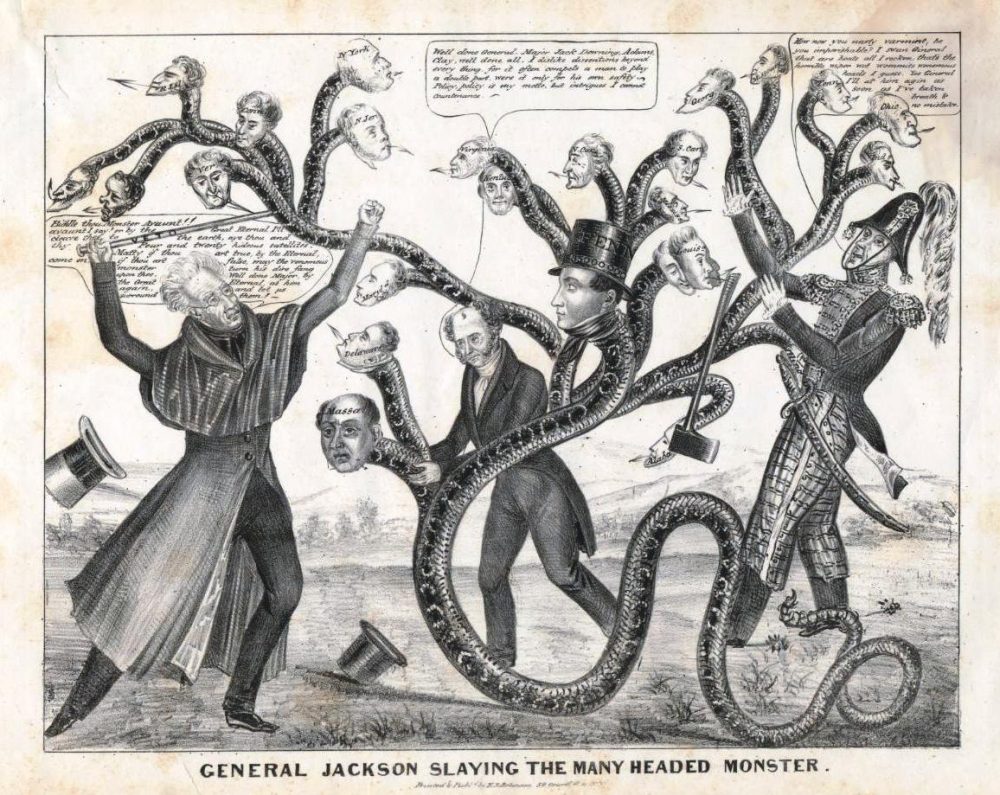

Andrew Jackson’s base loved his combative antics, but his moderate Whig rivals had longer-lasting impact. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Two centuries after he served as president, Andrew Jackson remains an enduring figure both in history—the 1820s and ’30s are known as “The Age of Jackson”—and in American political conversation, with Donald Trump associating himself with Old Hickory’s nationalism and populism.

Jackson’s contemporary notoriety, however, far exceeds his actual impact. To be sure, he remains well known for his “war” on the Second National Bank of the United States and for signing the Indian Removal Act, which resulted in the forcible eviction of thousands of Native Americans from their homes to lands west of the Mississippi River. But soon after he left the presidency, Jackson’s way of social, economic, and racial thinking was eclipsed—and it is not likely to be durably revived, by Trump or anyone else.

The true long-term winners of the “Age of Jackson” were actually his opposition—the Whig Party. After the 1860s, the Jacksonians’ articles of faith—agrarianism, states’ rights, and slavery—were relegated to history’s ash heap. It was the priorities of the Whig Party—the short-lived moderate party of antebellum America—that prevailed, and shaped the world to come.

The Whigs did not capture as many presidential elections as the Jacksonians (only two in five contests), rarely controlled Congress, and in 1854 dissolved into the Republican Party. But their party was in the forefront of modern American development in a way that the Jacksonians, a Southern-dominated coalition, never were. And thus its impact was both superior and lasting.

To say that the Whigs advanced a “modern” outlook is to note their support for what the Kentucky statesman Henry Clay called the American System, an economic plan to use the power of the central government to encourage internal improvements in the states. Canals, railroads, industry, and a more centralized banking system were to be the fruits of this program. Culturally, Whigs were known as the party of religious and educational reform. Typically, they were opposed to Indian removal and many were hostile to slavery. They comprised a coalition of entrepreneurs and evangelicals.

The Jacksonians’ unreflective emphasis on private capitalism and states’ rights came to a head in the disastrous Panic of 1837, which touched off a major recession that lasted for several years. The panic resulted from Jackson’s destruction of the Second National Bank, which had been a vital engine of development and financial regulation in the country. Jackson put the Bank on the road to extinction by vetoing an 1832 bill to recharter it, and then removing government deposits from the Bank. In the early 20th century, Congress would rectify his mistake—and acknowledge that Whiggery had gotten it right—with the creation of the Federal Reserve System.

During his Bank War, Jackson’s actions concerned many Americans. His rejection of the Bank bill was one of 12 presidential vetoes during his two terms—more than all the vetoes by the previous six presidents combined. Jackson sometimes refused to sign congressionally approved legislation that he merely disagreed with personally, which led to accusations that he was governing as a king rather than as a president.

Opposition to Jackson’s monarchal behavior was a big part of the Whigs’ identity. In fact, the very name “Whig” was chosen to align Jackson’s critics philosophically with the British Whig Party, thus portraying the Jackson camp as American Tories. In a similar vein, one of the Whigs’ biggest concerns was the growth of executive authority—a concern that was not only justified, it remains of vital importance in our republic today.

It’s also significant that Jackson’s opponent in two presidential elections, John Quincy Adams, is in many respects a more relatable figure to us than Old Hickory. His support for federal aid in economic development, his criticism of slavery, and his desire to see the United States move beyond a narrow agrarian states’ rights orientation were not always political winners in his own time. But they were positions that would push the Republican Party to victory in 1860, continuing in their modern permutations to inform economic and cultural conversations today. Perhaps that is why John Quincy Adams is such a hot topic for contemporary historians. Since 2013 no fewer than four major biographies—by Herb Giles Unger, Fred Kaplan, James Traub, and William J. Cooper—have appeared; earlier this year the Library of America released an edition of The Diaries of John Quincy Adams.

Whigs were not perfect, of course—they could be elitist, patronizing, and condescending. Too much a party of the Anglo, the industrial, and the educated, Whigs alienated some voters. But they also believed in societal unity—a view that contrasted with the slash-and-burn tactics of Jackson, who often spoke of irreconcilable interests in America and seldom sought compromise. Northern Whigs in particular, who were closer to industry and further from slavery than their Southern colleagues, demonstrated a far keener understanding of the challenges facing the nation by taking centrist positions on the vital issues of the day—counseling reform rather than destruction of the Bank, advising peaceful border negotiations with Mexico rather than war, and seeking to limit planter expansion into the country’s western territories.

Jackson and his party were undeniably the “victors” of the 1830s. But the Jacksonian vision collapsed within a generation and the Republican Party under Abraham Lincoln (a former Whig) put together a new American system that included a protective tariff, subsidized industry, and promoted education. These planks—along with the destruction of slavery—definitively overturned the Jacksonian order. Old Hickory may have carried the day, but his more moderate opponents won the war.

Send A Letter To the Editors