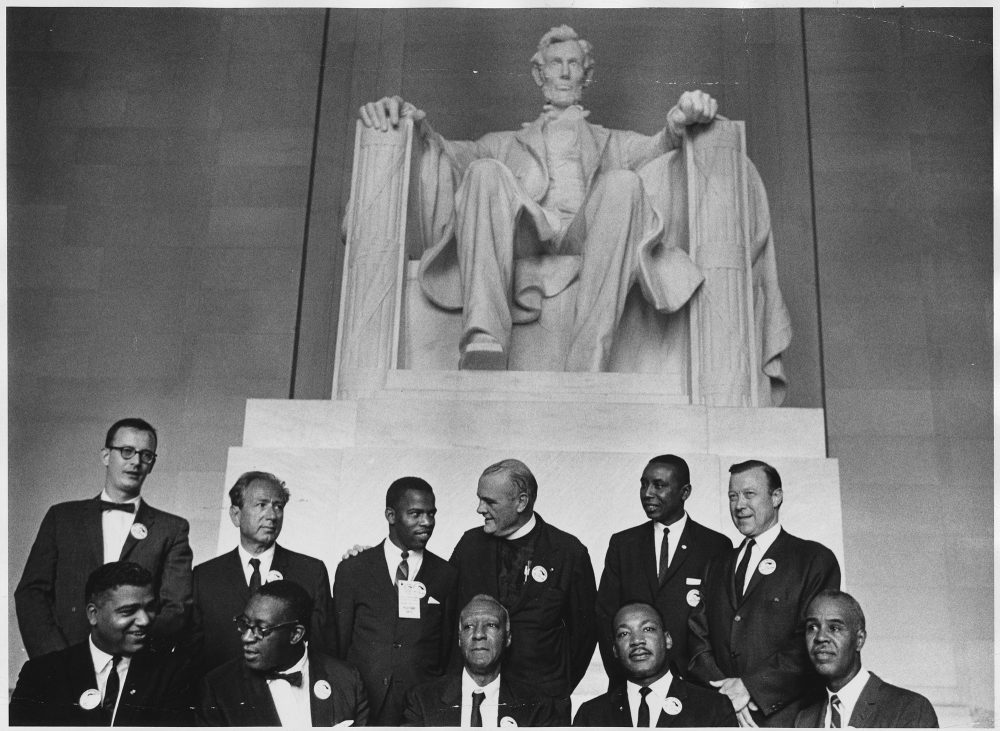

Leaders of the civil rights march on Washington, D.C., Aug. 28, 1963. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Every year about 20 million tourists come to Washington, D.C., to visit the marble monuments of American freedom and democracy. Few of them, however, realize that the 680,000 permanent residents of the nation’s capital must endure the cognitive dissonance of being U.S. citizens while suffering from the political tyranny that inspired our Revolution: taxation without representation.

Created by constitutional fiat and controlled by Congress, the District of Columbia is the undemocratic capital of this democracy. Washingtonians have no representation in Congress, and the decisions of their municipal government are subject to congressional veto. Furthermore, the city’s lack of political power and basic self-determination has had a profound influence on its history, placing it at the mercy of the federal government and forcing the city’s residents into a frustrating role as dependents and claimants, rather than full citizens.

At the center of the district’s struggle for democracy is the rawest issue in American history and politics: race.

Democracy and race have been inextricably intertwined in Washington since Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton cut a deal to place the nation’s capital on the shores of the Potomac. Safely ensconced between two slave states, the new federal district supported slavery and the slave trade from its inception, becoming the nation’s largest slave-trading city in the 1830s.

But, during the Civil War, D.C. became a magnet for former slaves, who helped create a progressive, biracial local government during Reconstruction. This exercise of black political power created a backlash, leading Congress to strip the vote from all Washingtonians, black and white, in 1874, ushering in a century-long period of disfranchisement and racial segregation.

Eventually, a locally driven, post-World War II civil rights movement toppled legal segregation and won the right to vote in local elections, but persistent racial inequalities remain to this day. An Urban Institute study found that in 2013 and 2014 white wealth in D.C. was 81 times greater than black wealth, and astronomical real estate values make it increasingly difficult for low-income residents to remain in the city.

As black educator and D.C. activist Mary Church Terrell articulated more than 100 years ago, no city better captures the ongoing tensions between America’s expansive democratic hopes and its enduring racial inequalities than the nation’s capital.

“Surely nowhere in the world do oppression and persecution based solely on the color of the skin appear more hateful and hideous than in the capital of the United States,” Terrell said, “because the chasm between the principles upon which this Government was founded, in which it still professes to believe, and those which are daily practiced under the protection of the flag, yawns so wide and deep.”

Terrell knew that what she was saying was not literally true. She herself embodied the potential and achievement of the D.C.’s black elite. The daughter of former slaves who became wealthy business owners, she graduated from Oberlin College, traveled the world, and taught at D.C.’s M Street High School, the top black secondary school in the country, before being appointed to the city’s school board. Washington offered Terrell and other black people significant opportunities unavailable anywhere else in the South, which in the early 20th century sank into an abyss of lynching, debt peonage, and codified segregation. There were indeed more hateful and hideous examples of racism and persecution than what she experienced in Washington, D.C.

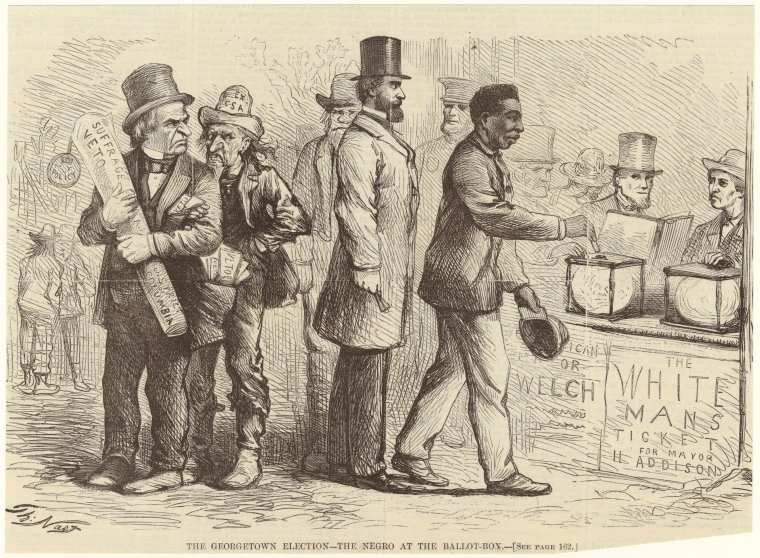

An 1867 cartoon by Thomas Nast depicts an African American man casting his ballot in the mayoral election for Georgetown, which was a separate municipality from Washington, D.C. until 1871. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collection.

Yet her point underscored something critical about Washington: It is the stage for American democracy, the parade ground where we celebrate our ideals and put them on display for the world. Whether considered to be “an example for all the land” (as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner called the district during Reconstruction) or “the showpiece of our nation” (as President Dwight Eisenhower claimed in the 1950s), D.C. is a symbol of the country and the embodiment of its democratic hopes.

Because of this symbolic significance, D.C. also has long served as a battleground for major political fights over race. During the long struggle over slavery that consumed much of the nation’s first century, the city became a focal point. For abolitionists, Washington was, as William Lloyd Garrison declared, “the first citadel to be carried” in the battle to end slavery nationwide. For Southern slaveholders such as South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun, Washington was a crucial barometer of Southern power: If D.C. should fall to abolitionism, then so too would the rest of the South, they feared. Abolitionists flooded Congress with so many petitions demanding an end to slavery and the slave trade in D.C. that in 1836 Congress imposed the infamous “gag rule” prohibiting any public discussion of the issue in the national legislature.

D.C. is also a fertile laboratory for ideas. Because Congress has ultimate authority over the district, its members often use the city as a petri dish. Sometimes, this approach benefits the cause of racial equality. During the Civil War and Reconstruction, Radical Republicans in Congress ignored the vocal opposition of white voters in the city to push through a series of racial reforms, including emancipating D.C.’s enslaved population in 1862, establishing black public schools, and granting black men the right to vote in 1866. It was an extraordinary and important social revolution—but it was not democratic.

At other times, national meddling has proven catastrophic to the city. In the 1950s, federal lawmakers, urban planners, and city boosters used Washington as a testing ground for “urban renewal,” a federally supported effort to use modern planning to revitalize and redevelop crumbling residential areas.

With sanction from the Supreme Court in its 1954 Berman v. Parker decision, which allowed public officials to take property and give it to corporations for redevelopment, urban renewal led to the wholesale destruction of poor, predominantly black neighborhoods in D.C.’s Southwest quadrant. At a cost of about $500 million (about $4.6 billion in 21st-century dollars), developers destroyed 99 percent of Southwest’s buildings, forced 1,500 business to move, and displaced 23,000 residents. In their place came 5,800 new housing units for a population half its original size. The racial demographics of Southwest flipped. In 1950, the area had been almost 70 percent black; in 1970 it was nearly 70 percent white, at a time when the black population was growing rapidly in the rest of the city.

The catastrophic impact of urban renewal helped inspire an era of grassroots citizen activism throughout the city. From the late 1950s through the late 1970s, black and white activists fought back against the business interests and unelected officials who ran Washington, challenging embedded economic inequalities in the black-majority city. Mobilizing citizen power, they pushed for self-determination, community control, and participatory democracy.

Some of these battles have been won. After a century of complete disfranchisement, in 1973 city residents regained “home rule” (municipal self-government), including a remarkable space for neighborhood autonomy in the form of elected Advisory Neighborhood Commissions. The early 1970s also witnessed the triumphant climax of the anti-freeway movement, an interracial, cross-class coalition that successfully challenged the vast network of city freeways envisioned by Congress, local officials, urban planners, and boosters in the press. And in those neighborhoods saved from the wrecking ball, tenants organized against slumlords and gentrification to establish their right to the city.

Other battles are ongoing. Local activists still struggle to build adequate, affordable housing and prevent displacement amid a new, 21st-century burst of gentrification. And the district still lacks any representation in the national legislature (a fact emblazoned in capital letters on D.C. license plates).

With these battles still to be won, it is no wonder that Washingtonians, people who daily live in the shadow of the great temples of American democracy, cast a critical eye on the celebrations of American freedom that take place therein.

Send A Letter To the Editors