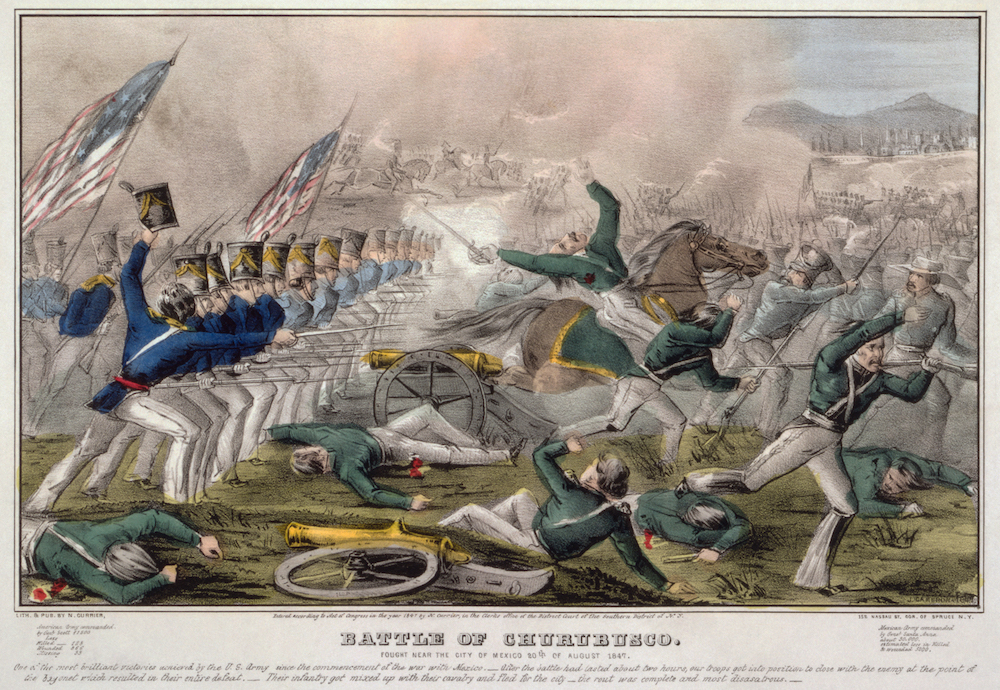

“Battle of Churubusco -Fought near the city of Mexico 20th of August 1847 / J. Cameron.” Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

No sooner had the U.S. Revolution ended than U.S. expansionists began looking south and southwest toward lands controlled by Spain.

No sooner had the U.S. Revolution ended than U.S. expansionists began looking south and southwest toward lands controlled by Spain.

The personification of this complicated project was the American poet-politician Joel Barlow. As a poet, he worked on creating public sentiment to annex Spanish lands, and, wearing his political hat, he pursued that agenda. Barlow is largely a forgotten figure today, but the myths he helped create remain with us.

Barlow was the likely author of the 1792 manuscript “Plan proposé pour faire une revolution dans la Louisiane” (“Proposal to Incite a Revolution in Louisiana”). The proposal detailed an illegal plot to incite a rebellion against the Spanish in Louisiana that would result in the transfer of sovereignty in the region back to the U.S.-friendly French. Such a transfer, according to the plan, would liberate the hemisphere from Spain’s policies of discouraging her colonies from international trade while increasing commercial opportunities for the fledgling United States. The manuscript was circulated between French and U.S. agents and French authorities, was likely intercepted by the Spanish, and is now housed in the Spanish archives of foreign correspondence. (It was republished in the 1896 Annual Report of the American Historical Association.)

It may seem hypocritical for representatives of a nation with a history in anti-colonial revolution and a national identity rooted in celebrating self-determination to seek to justify excursions into Spanish-controlled lands. To satisfy this ideological conundrum, early U.S. expansionists developed a mythology of Hispanicism that resembled, in some ways, European Orientalism.

The term “Orientalism,” coined by Edward Said in his famous 1978 book of the same name, is used to refer to stock Western representations of the Middle East as backward and exotic. Hispanicism similarly comprises simplifications regarding the nature of Spanish-speaking peoples. It racialized such peoples as criminal, lethargic when it came to new enterprises, and inclined to autocratic forms of politics. Hispanicism allowed U.S. expansionists to argue that Spanish-speaking peoples lacked legitimate claim to the state sovereignty they enjoyed. By the same myths, only Anglo-Americans were sufficiently dedicated to the possibilities of liberal democracy and capitalism to make the most of their privileges.

Sketch of Joel Barlow. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Literature was a primary method for this myth-making. In early U.S. culture, the lines between what we now consider different forms of writing—such as poetry, journalism, and scientific discourse—were blurred. Literature was not viewed as an ethereal aesthetic realm, but was used to contribute directly to public discourse, often by sowing images and stereotypes that served to recommend policies. For instance, James Fenimore Cooper’s acclaimed Leatherstocking Tales contributed to the solidification of stereotypes regarding Native Americans, legitimating brutal campaigns against them. Similarly, poetry and fiction regarding Spain and Spanish America shaped U.S. attitudes about Spanish-speaking peoples.

Barlow was a case in point. When he wasn’t speculating in land, planning revolutions, or working in politics, Barlow was an early U.S. literary nationalist whose poems The Vision of Columbus (1787) and its more classicized revision The Columbiad (1807) were early and widely noticed attempts to create a U.S. national epic. The poems tell the story of how Columbus, languishing in a Spanish prison, receives a visit from an angel who consoles him with gratifying visions of the civilizations that will emerge in the lands he discovered. The visions conclude with the fledgling United States’ anti-colonial revolution and innovations in political freedom, which Barlow presents as the end point of the narrative of progress initiated by Columbus’ discoveries.

The poems’ villain is Spain, which Barlow presents as antagonistic to progress in the New World. Barlow’s prose introductions frame the poems with descriptions first of Spaniards’ failure to appreciate Columbus’ imagination and then of the Spanish court’s ungratefulness for the benefits the explorer’s achievements conferred upon Spain. As the narrative continues, Barlow often dwells on the Spanish conquistadors’ crimes, writing of Hernán Cortés as follows:

Thine the dread task, O Cortez, here to show

What unknown crimes can heighten human woe,

On these fair fields the blood of realms to pour,

Tread scepters down, and print thy steps and gore,

With gold and carnage swell thy sateless mind,

And live and die the blackest of mankind.

Of course, the Spanish were hardly the only colonists responsible for indigenous suffering. The British had a long history of such responsibility. Anglo-Americans, during and especially after Barlow’s poems were being published, were working towards the systematic removal of native peoples from the eastern United States. Barlow ignored these matters, though.

Instead, he celebrated the United States as a bastion of freedom and progress. In this false contrast between Spain and the United States lies Hispanicism’s basic premise: demonizing Spain as a place opposed to innovation and liberty for the purpose of celebrating the United States’ devotion to these goods.

Barlow’s dual career illustrates Hispanicism’s role in geopolitical affairs. As a man of letters who established a distinctly U.S. literary tradition, Barlow popularized the Hispanicist myth that Spaniards, with their despotic political leanings and antipathy towards energetic individualism, were foes to political and commercial progress. Then, as a diplomat tied to Thomas Jefferson, he put this understanding of national identities to work in advocating for U.S. expansion into Spanish territories.

Barlow relied on longstanding Northern European tropes regarding Spain. Many of these stereotypes had emerged in the early modern period as Spain’s colonial rivals, principally England, contested the moral legitimacy of Spain’s 17th- and 18th-century colonial predominance. As illustrated in Barlow’s verse depiction of Cortés, the “Black Legend” of Spain’s colonial depravity fixated on images of the conquistador’s violence against defenseless natives.

The “Black Legend” also contained a prominent religious element: Northern European and colonial Anglo-American Protestants, who were committed to individual engagement with scripture, perceived Spanish Catholicism and its appeals to clerical hierarchy and church tradition as a religion intent on enforcing ignorance upon its lay adherents. Protestants connected this obedience to church authority with efforts by Spain’s monarchy to undermine the average Spanish subject’s liberties. These views were embodied in myths depicting the Inquisition’s gothic horrors.

This “Black Legend”-derived Hispanicism evolved during the 19th century in ways that suited the emerging U.S. market society and national imperial aspirations. Hispanicist-invested writers increasingly fixated on Spanish-speaking peoples’ supposed aversion to the entrepreneurial individualism necessary for market success and the managerial aptitude needed to direct large enterprises and empires.

Herman Melville made such ideas central to his ironic 1855 novella, Benito Cereno. Usually read as a commentary on slavery, Melville also criticized Hispanicism and U.S. imperialism in this work. The tale’s protagonist, Amasa Delano, thinks of himself as an ideal U.S. managerial type: a skilled, stern, yet benevolent leader. When Delano encounters the San Dominick, which he initially believes is a distressed Spanish slave-trading vessel seeking his aid, he ascribes these distresses to the “incompetence” of its commander, the Chilean creole Benito Cereno.

With a hint of racial condescension as he notes Cereno’s “small, yellow hands,” Delano negatively judges Cereno’s leadership because his chain of command lacks “stern superior officers.” Delano thus comes to believe it is his duty to assume Cereno’s command. Because he believes he would be doing so for Cereno’s own good, the U.S. captain imagines himself to be “lightly arranging” Cereno’s affairs rather than heavy-handedly assuming an authority he does not possess. Delano thus represents the imperialist who thinks of U.S. expansion into Spanish America as a paternalist effort to benefit Spanish-speaking peoples by making better use of their natural resources than they would.

But Delano’s impressions of the San Dominick are mistaken. Its slaves have successfully revolted, those absent superior officers all killed. The revolt’s leader, Babo, has instructed Cereno and the other surviving Spaniards to ascribe the disorder on the ship to distresses other than revolt—and to play to Delano’s preconceptions regarding Spaniards so as not to raise Delano’s suspicions. Cereno even donned his picturesque Chilean attire, it is revealed, as part of Babo’s plot.

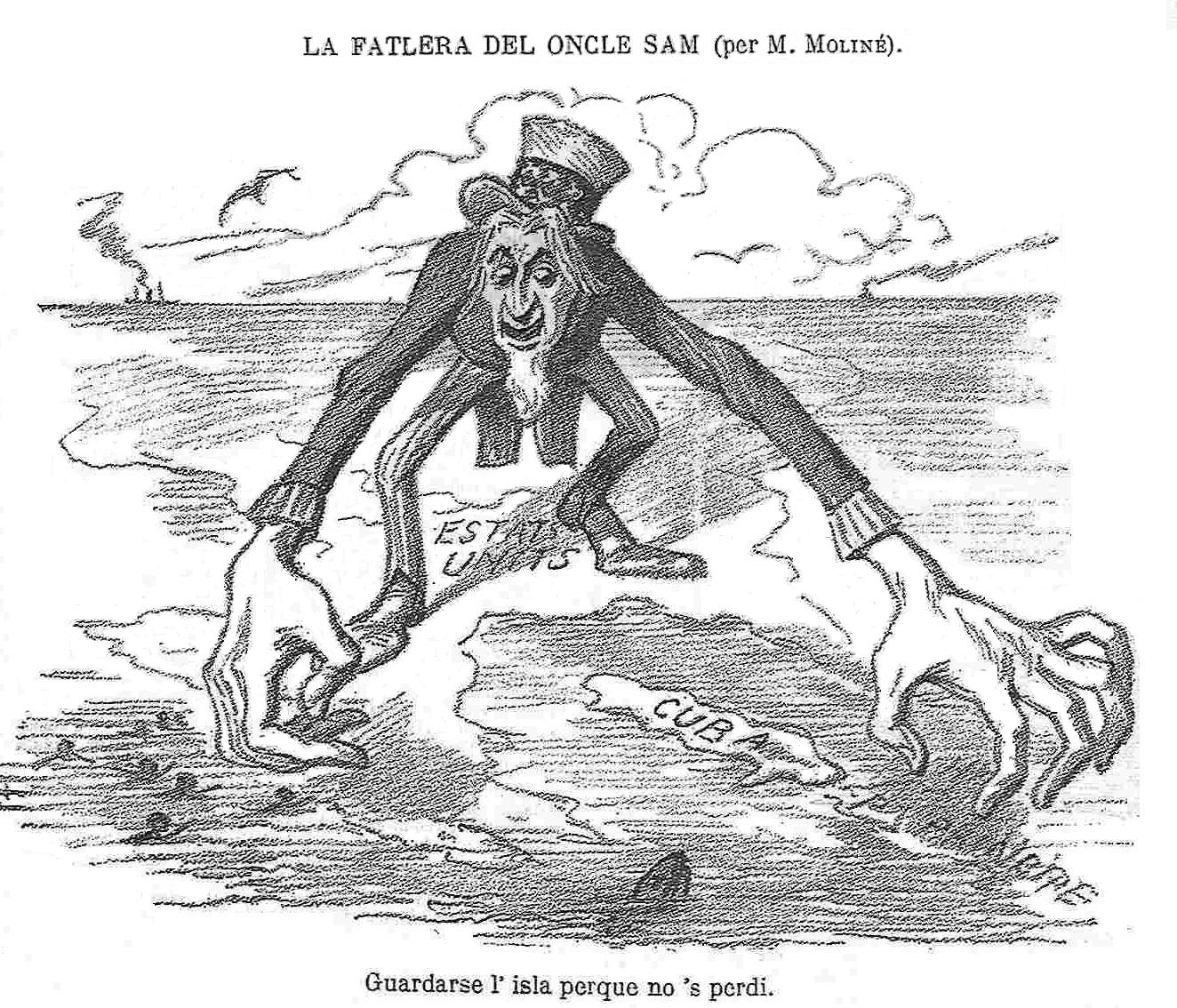

1896 Sketch from the Catalan newspaper La Campana de Gràcia satirizing the U.S.’s intentions in Cuba.

Babo’s goal is to induce Delano, either by deception or by killing the U.S. captain and his crew, to provide the supplies necessary for Cereno to sail the blacks back to Africa. Delano does not know that his life is at risk on the San Dominick. He narrowly escapes being murdered and then leads a violent counter-revolt that results in the re-enslavement of the Africans. Delano’s reliance on Hispanicist stereotypes—along with his racist failure to recognize the capacities of the African slaves—nearly costs him his life as he misperceives the dangers surrounding him.

As Melville recognized, the deployment of these stereotypes to advocate for such policies has psychic roots in U.S. exceptionalism. Exceptionalism motivates Americans’ desire to feel different and better than their Spanish-speaking neighbors, which cyclically spurs Americans’ avid proliferation of Hispanicism in the national culture.

Melville’s haunting novella also serves as a cautionary tale as we wrestle with contemporary manifestations of Hispanicism. The Hispanicism that emerged in the 18th century underpinned later moments of conflict between the United States and the Spanish-speaking world—the U.S.-Mexican War; the Spanish-American War; U.S. anti-communist intervention in Latin America during the Cold War; and the United States’ domestic nativist strife over immigration from Mexico and Central America. Expansionism and interventionism have repeatedly been justified by arguments regarding the supposed inability of Spanish-speaking peoples to manage their domestic affairs, while support for restrictive immigration policy has been defended by specious appeals to these peoples’ inherent criminality.

But Benito Cereno also powerfully illustrates the problem with this tendency: Spanish-speaking peoples are as diverse as humankind in general, and the idea that differences between such peoples and Americans can be reduced to simplistic oppositions is as much a fiction as the elaborate web Babo spins for Delano.

Send A Letter To the Editors