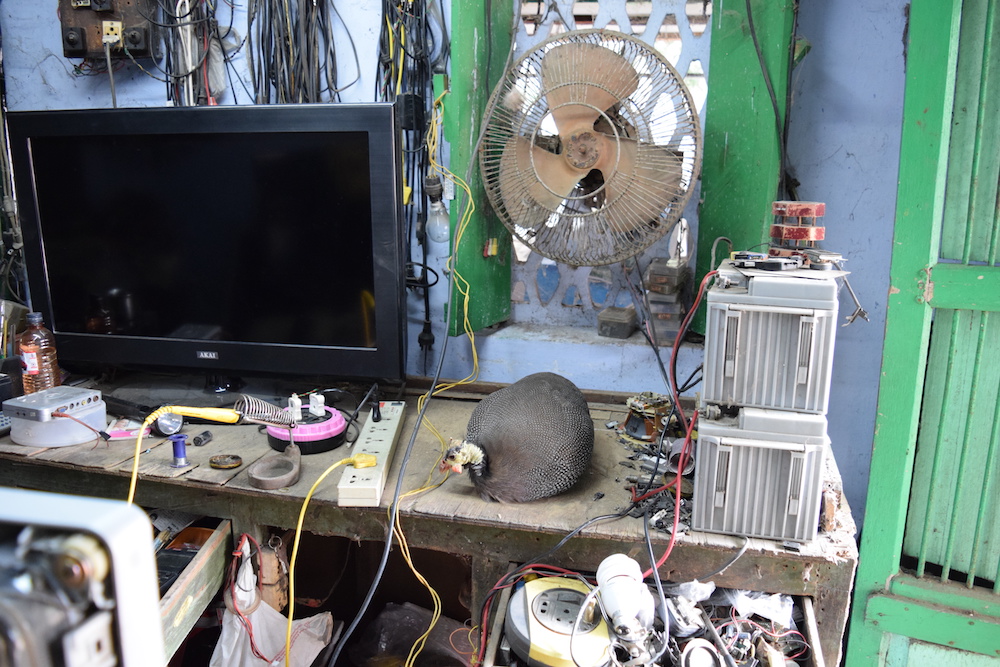

A chicken belonging to the repairman sits on the counter of a repair shop in the town of Repaile, Andhra Pradesh. Courtesy of Padma Chirumamilla.

In a repair shop in South India, an employee was sitting next to me, trying to figure out what was wrong with the circuit board on his worn blue work table. The board was from a large, expensive flat-screen television lying face-down in front of us; the customer was due to return in another day or two.

As he prepared to examine the circuit board under a bright magnifier lamp, the power cut out across the service center. The soldering iron, the lamp, the shop’s overhead lights, and the ceiling fans all stopped working. Narendra (not his real name, but used here to protect his privacy) sighed before going to look for the battery-powered generator at the other end of the shop. It was his responsibility to get the overhead lights and fan working again in the boss’s office. The television would have to wait.

Such deep-summer rolling blackouts were a common occurrence. Still, in the electronics service center where I worked alongside Narendra in 2016, the irony was not lost on anyone. Here we were, trying to fix expensive consumer electronics like flat-screen televisions, refrigerators, and audio systems, and the very thing needed for their functioning was out of order. When the power would return—and these devices might be returned to functionality—was anyone’s guess.

Technology—especially the consumer electronics that saturate our everyday lives—is laden with futuristic promises: the promise of seamlessness, the promise of constant connectivity, the promise of invisible function without disruption. GE announces that “laundry time shouldn’t interrupt family time” with its Wi-Fi-connected washing machines and dryers, some of which can also be voice-controlled. “Go ahead and talk,” GE invites us, “your Wi-Fi appliances will respond.”

Reality, however, comes up short of the vision of appliances that require no thought to maintain and no special care to update. Nowhere are the contradictions of this dream clearer than in the places responsible for ensuring that these appliances will work.

I had gone to South India to study the labor of small-town service technicians and get a better understanding of the kind of work and knowledge necessary to keep these devices working. A typical workday alternated between waiting for parts to be delivered from authorized suppliers and trying to help consumers who owned devices that the corporation no longer guaranteed or supported, like old cathode-ray tube (CRT) televisions and obsolete DVD players.

A pile of circuit boards from older CRT televisions in an independent repair shop in the town of Guntur, Andrha Pradesh. Courtesy of Padma Chirumamilla.

The center was staffed almost entirely by men, save for the reception area, which was run by two women, who were also responsible for ensuring the paper trail tracking each device in and out of the center was kept up to date. In the audiovisual section, where I conducted most of my research, the service technicians were men of varying ages and educational experiences. Some had studied at government-run “industrial training institutes,” others at privately-owned and operated technical institutes, while still others held engineering degrees and were working on six-month internships to learn through “experience.” One of the bosses complained that he couldn’t get “quality” hires who were technically skilled and appropriately professional, who could live up to the international image of the parent corporation.

In 1960, the journalist Vance Packard wrote in The Waste Makers that, “…when in a joking mood, [businessmen] sometimes ask the definition of the phrase ‘durable goods.’ Their playful answer: any products that will outlast the final installment payment.”

In India, when goods that had indeed outlasted the final installment payment showed up at the service center, it was up to the individual service technician to decide whether it was worth his while to attempt the repair. Given that the service center could pocket whatever money it made from repairing these old devices without reporting the income to corporate overseers, there was an ulterior motive to help customers save their old, often well-loved devices.

The service center, Narendra told me, didn’t pay particularly well, though as an experienced technician, he managed to provide for himself, his wife, and two boys. Entry-level technicians made far less, and they had no formal system of advancement or any real job security. Boredom pervaded the atmosphere between shipments of parts. Because the corporation so tightly controlled and monitored both functional and defective parts for their latest devices, the technicians had no spare parts to tinker with.

They had more freedom with the “obsolete” CRT televisions that were out of warranty and thus out of corporate mind. So Narendra spent a considerably longer time fixing the CRT televisions than he did the newer, pricier flat-screens. He could examine the television’s circuit board directly and isolate the exact problem or set of components that he needed to replace, instead of merely determining whether a new part needed to be ordered from a predetermined list, and then installing the part when it finally arrived.

Of course, the service center didn’t guarantee or even formally authorize any of the work performed on CRT televisions. Whenever a formal inspection from regional headquarters was due, harried technicians would clear away traces that they even performed this kind of repair work. Though these jobs paid less, Narendra found the process more satisfying.

His discontent with the process for the newer devices mirrored a broader concern I heard among many television repairmen I interviewed: their labor—and even the notion of the television as a thing that ought to be repaired when it failed—was being sidelined by the convenience of a “use-and-throw” ethos. With the increasing availability of pay-in-installment schemes and the arrival of cheaper Chinese brands in the small-town market, the basic economic viability of repairing ordinary consumer electronics had been thrown into question.

Writing in The Baffler, historian and activist Maximillian Alvarez notes that the desired domain of tech giants is “a utopia from which there is no way out, where life itself waits for ‘upgrades’ and adjusts to new formats, functions, restrictions, and protocols that are crafted in secret, delivered from afar, and serviceable only by those technical support outposts that bolster their bottom line and solidify their market dominance.”

The service center where I worked certainly fit that model. For the newer models of flat-screen televisions, the defective parts from customers’ sets were carefully bagged, individually labeled, and locked in the boss’s office until they were shipped back to regional headquarters. Attempting individualized repairs on newer flat-screen televisions was mostly disallowed—and even rendered infeasible by the growing physical fragility and complexity of television screen technologies and circuit boards.

What is at stake with the increasing dominance of “use-and-throw” as an ethic that guides our attitude towards the objects within our everyday lives? One answer is that we are losing the ability to maintain a life independent of the surveillance that corporations embed within their devices. Another answer is that small-scale repair practices are becoming less viable, so we are losing the longevity of many objects that shape our daily rhythms.

Only 20 percent of electronic waste is documented and recycled. Disposability is an inherently unsustainable ethic to live by, and one that relies upon the cruelty and constancy of global supply chains to maintain its façade of ease.

The repair shop poses to us, as first-world consumers and users within a startlingly dense world of goods, a simple question: Are there other means by which we might live with the objects in our lives, beyond a relation of utilitarian usage, convenience, and disposability? The popularity of Marie Kondo’s stuff-organizing strategies (based on the Japanese concept of tokimeku, “sparking joy”) or the trappings of Danish hygge (“coziness”) suggests that other ways of living and being with goods do exist.

What sort of future and people do we forsake in relegating ourselves to an ethic of “use-and-throw” with the stuff of our everyday lives? If the unease of the television repairman is any indication, these are questions we need to answer.

Send A Letter To the Editors