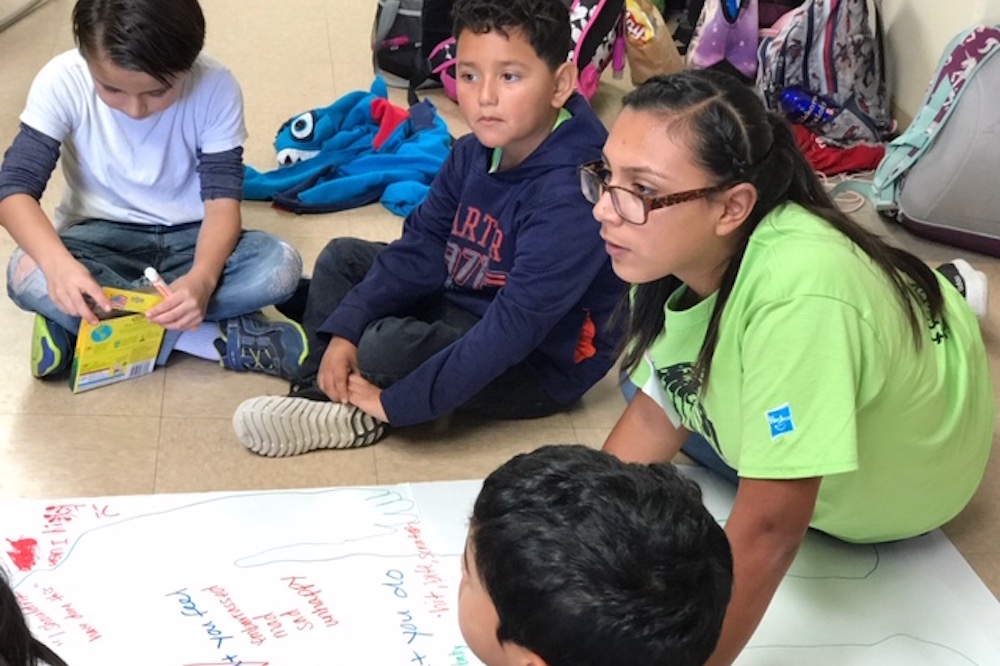

Cindy Aguilar, 16, leads a “Kindness Challenge” at a camp that the city sponsors during school break. Courtesy of the City of Gonzales.

What if California actually decided to put the needs of its poor kids first? What would that look like?

Here’s one answer: it might look like Gonzales, a small city of 9,000 people—many of them farmworkers—along Highway 101 in the Salinas Valley.

The people of Gonzales don’t have educational credentials (less than 10 percent of adults over 25 have a college degree) or wealth (the median income is less than $17,000 annually). But they do have one incredible resource: youth. Thirty-six percent of the population is under the age of 18, and about 1,000 of the 9,000 residents are under age five. More than 85 percent of the Gonzales Unified School District qualifies for free and reduced lunch.

Very much against the odds, Gonzales has relentlessly assembled a rich suite of supports and services that touch the lives of every young person in town, from pre-school through high school. Today Gonzales has so many different programs for youth—service programs, recreational programs, after-school programs, summer programs, job programs—that it is now the rare California city spending more on youth than on its fire department.

As Gov. Gavin Newsom seeks to deliver on his campaign promise of a new system to support children from the womb through the college dorm room, Gonzales should serve as inspiration—and a reminder that there are no good excuses for not doing more for California’s kids.

Gonzales residents are poor, but they still voted for a half-cent sales tax to fund enhanced services, like youth services. And while leaders in the small city don’t have much power, that didn’t stop them from creatively sharing that power—and granting Gonzales children the authority to help make decisions about how money is spent. The kids even shape policy through a separate youth version of the city council.

Gonzales, for all its challenges, has real strengths. It has developed an industrial park of food processors and agriculture-related businesses that produce steady tax revenue. And, despite being a city of migrant workers, it has stable and thoughtful local leadership. City manager René Mendez, who also coaches the high school’s tennis team, notes that when two new city council members were sworn in recently, one was the former police chief and the other was the wife of a former councilmember who decided to hire him 16 years ago.

Early in his tenure, Mendes asked the city council members to make drawings of what was most important to them in Gonzales. They all drew pictures of parks, playgrounds, and other places for kids. That exercise triggered a shift in the council’s focus to children. Also guiding the shift were recommendations from Youth for Community, a panel of young people convened with help from city police and the Monterey County Office of Education. Ultimately, the city and the school district created a partnership called Gonzales Youth 21st Century Success Initiative.

The city started by developing year-round sports offerings and an aquatics program. Later, the city added full-day, five day-a-week summer camps that working parents can afford ($50 a week) and that keep kids physically active and engaged with community. The city now provides this same full-day coverage during spring break, winter break, and any other weekday when schools are closed.

“Our attitude is: if we don’t have the money, we’re going to find the money,” says Sara Papineau-Brandt, the parks and recreation chief, who has led the ramp-up of programs.

In 2016, the city joined with the school district to launch a robust after-school program, with a focus on homework assistance. It now serves 226 kids in elementary and middle school.

Still, Mendez and Papineau-Brandt note that most child care in this city where people work long hours in the fields is provided by grandmothers, or other family and friends, who have little training in early childhood development. So the city applied for and won a United Way grant to start a program called the Friends, Families & Neighbors Playgroup, in which caregivers learn how to handle challenges with the children they care for. The city is also working on initiatives that would create a city pre-school program that could also help the city’s’ informal caregivers become licensed.

When test scores showed the town’s high school students underperformed in math, the city funded a STEM program for middle and high school students called Wings of Knowledge, which uses math and science to tackle real-world technology challenges. (One project involved building, placing, and collecting data from digital soil monitoring devices that help farmers manage water usage).

As much as possible, Gonzales employs the city’s own children as part-time workers or interns in its programs. Students as young as 9th graders are asked to interview and fill out applications—giving them experience. The city also gives part-time work to college students from Gonzales to keep them connected to the town.

How does a town like Gonzales, where per capita income is half that of the state, manage to do better than many wealthier communities? Mendez, the city manager, says Gonzales has more money for kids because it limits spending on other things. The city doesn’t offer retiree health benefits, which have been a big burden for other cities, and it keeps its police force small, which provides significant savings since police are the biggest part of municipal budgets. Gonzales can do this because crime is low—property crime is 40 percent below state averages, and the robbery rate is 60 percent.

Is there some kind of virtuous circle between youth programs and low crime rates? Gonzales officials say they can’t be certain whether their emphasis on youth has led to low crime. But it sure doesn’t hurt.

Gonzales isn’t immune from the problems of California cities. There is a lack of housing both for existing residents and for teachers and other professionals being recruited there. In response, the city is annexing land and pushing for new housing development, with developers paying their impact fees by providing school facilities, day-care centers and other services for young people. In Gonzales, many wonder whether new state investments, especially in pre-school and early childhood, will prioritize smaller cities that often struggle to compete for grants.

Here’s hoping that the state, in doing more for children, also embraces the democratic spirit of Gonzales. In the after-school program, middle schoolers meet with staff weekly to decide on activities. And when the city had to put in a new playground structure at its tot lot, staffers were required to give a presentation on different options to kindergarten and transitional kindergarten students. The kids then had a binding vote to determine which structure would be purchased. “No one over the age of 5 got to vote on that,” says Papineau-Brandt.

I got a taste of youth democracy recently in the city council chambers, where the Gonzales Youth Council meets two Wednesdays a month. In 2014, the city and school district jointly appointed two youth commissioners, who are 18 or younger and attend city council and school board meetings; those commissioners lobbied to create the Youth Council, which consists of middle and high school students who go through an application process to serve.

“We were trying all this stuff for kids, and for some of it, kids weren’t showing up at first,” says Mendez. “The fundamental idea for the youth council was to bring the kids in so we could see what we were missing.”

Youth Council members set their own agenda and take on various tasks, from organizing the city holiday celebration to researching local cannabis regulations to hosting workshops for young people (one recent one was about college applications). Youth council members even handled the sensitive job of surveying the community about police department conduct; the idea was that immigrant residents, who are wary of federal immigration authorities, would be more likely to speak with the young people.

The Youth Council can also make policy. In 2017, the Council held hearings and drafted a new and comprehensive ordinance on underage drinking that replaced a heavy fine on parents who served alcohol to minors with a requirement that those parents take an educational course. This ordinance was unanimously adopted by the city council.

At the meeting I attended, the Youth Council discussed ongoing efforts to reduce extracurricular fees charged by the school district, and to increase transportation for kids who attend Gonzales schools but live in small communities outside the city limits. Youth commissioner Cindy Aguilar, a high school senior, explained their effort to create a Youth Innovation Center, with computer labs, a maker space, and a music studio. Sales-tax dollars are helping the project, but the council will need to raise money as well.

“We got to meet again with the architect,” said Aguilar. “We said we wanted it to smell like chocolate chip cookies.”

Don’t be surprised if the Gonzales kids get what they want. With representation comes power. And if California is serious about putting kids first, the state should form its own youth legislature.

Send A Letter To the Editors