How the U.S. Designed Overseas Cemeteries to Win the Cold War

From France to the Philippines, Stunning Landscapes of Infinite Graves Displayed American Sacrifice and Power

Americans commemorate our fallen soldiers differently than other countries do. You can see the difference most clearly overseas. While innumerable war cemeteries in Europe and the Philippines account for the dead from all participating nations of World War I and World War II, only the American war cemeteries feature highly designed landscapes and major works of art and architecture.

Americans commemorate our fallen soldiers differently than other countries do. You can see the difference most clearly overseas. While innumerable war cemeteries in Europe and the Philippines account for the dead from all participating nations of World War I and World War II, only the American war cemeteries feature highly designed landscapes and major works of art and architecture.

The decision to build these monuments and place them in park-like cemeteries reflects the Cold War of the 1950s as much as the World Wars that these sites commemorate. Over time these cemeteries helped establish an idealized American legacy in Europe, one that told the story of triumph over evil. Among the ideas these memorials convey is an insistence on Christianity as a spiritual beacon. They also offer an artistic presentation of American militarism with the aim of teaching a pointed lesson about the vastness of American power.

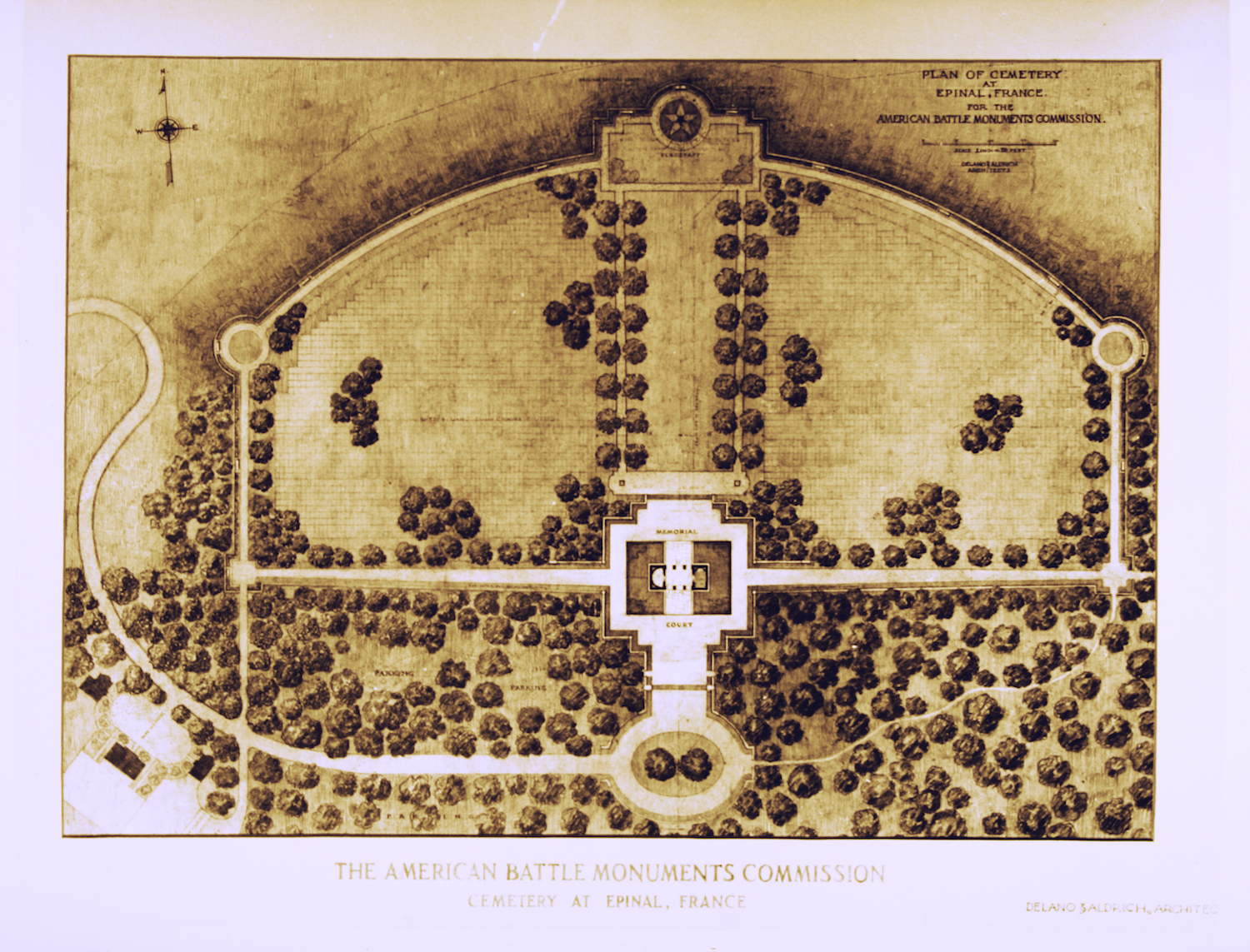

Five American World War II cemeteries in France offer a window into the 23 worldwide war cemeteries and 11 monuments built by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC). These five are the permanent burial sites for approximately 30,402 Americans, and like most American war cemeteries, the sites are located on or near the former battlefields: Omaha Beach and the Cotentin in Normandy; the Vosges Mountains and the German border area in Lorraine; and the assault beaches in Provence.

The World War II cemeteries were the first multi-site, government-funded design project after the war. During the initial phase of the American war cemetery, there were 24 temporary American burial grounds in France for just under 87,000 graves. Between 1947 and 1949, 64 percent of these bodies were repatriated upon request of the next of kin. The rest of the fallen soldiers were buried overseas, a decision made for the most part by their families. By 1949, only five of the original 24 cemeteries remained.

Between 1948 and 1952, designs for these five permanent sites in France were finalized and construction began in 1952, concluding in 1956. The care and maintenance of American graves was placed under the official auspices of the American government, and to this day the cemeteries are the responsibility of the ABMC and paid for by American tax dollars.

It is no coincidence that American government officials planned the cemeteries in the height of the Cold War and almost immediately after the United States State Department designated France as the key battlefield between Communists and the West in 1947. U.S. officials had been panicked since the elections of October 21, 1945, when the Parti Communiste Français—the French Communist Party—won 365 seats out of 586 in the French parliament, 62.2 percent of the whole. And, as illustration artist J. N. Darling noted in his political cartoon of 1947, French Communists were aggressively commandeering the postwar economy.

The ABMC coached the artists and architects of the American cemeteries to promote Judeo-Christian beliefs in redemption, and principles of freedom and democracy, through pictorial images, inscriptions, and structures. The ABMC felt that the stunning landscapes of infinite graves, coupled with such impressive messages and stately works of art and architecture, would make unforgettable, ever-lasting reminders of American sacrifice for a European audience. They also believed that the cemeteries would be stages for influencing and supporting diplomacy, both in day-to-day and anniversary occasions. Looking at such cemeteries, French citizens surely would wonder at their own political leanings, including Communism, the Americans thought. And who was to say that the United States military would not come back to Europe and sacrifice again for their capitalist ideology, since it had done this already—not once, but twice?

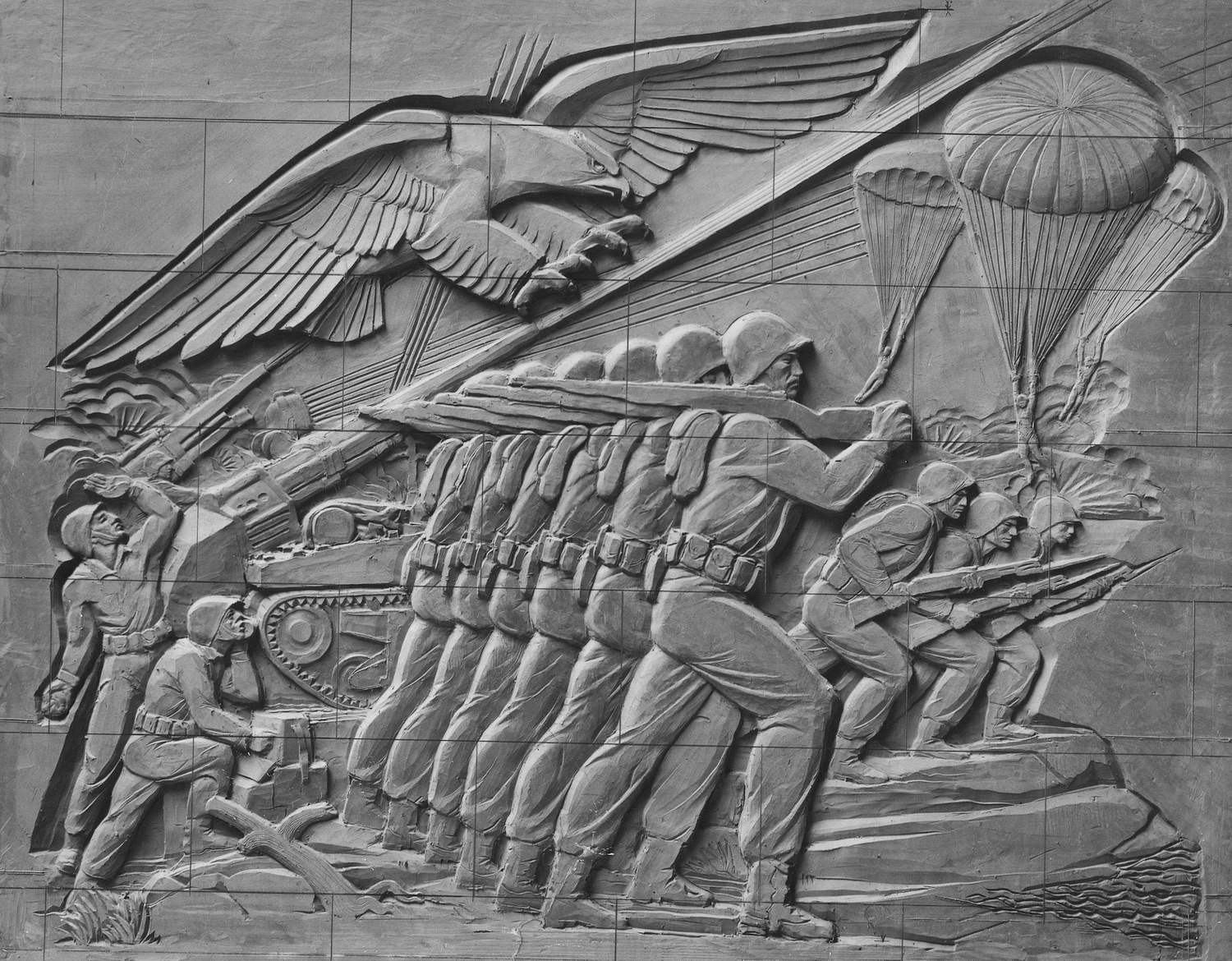

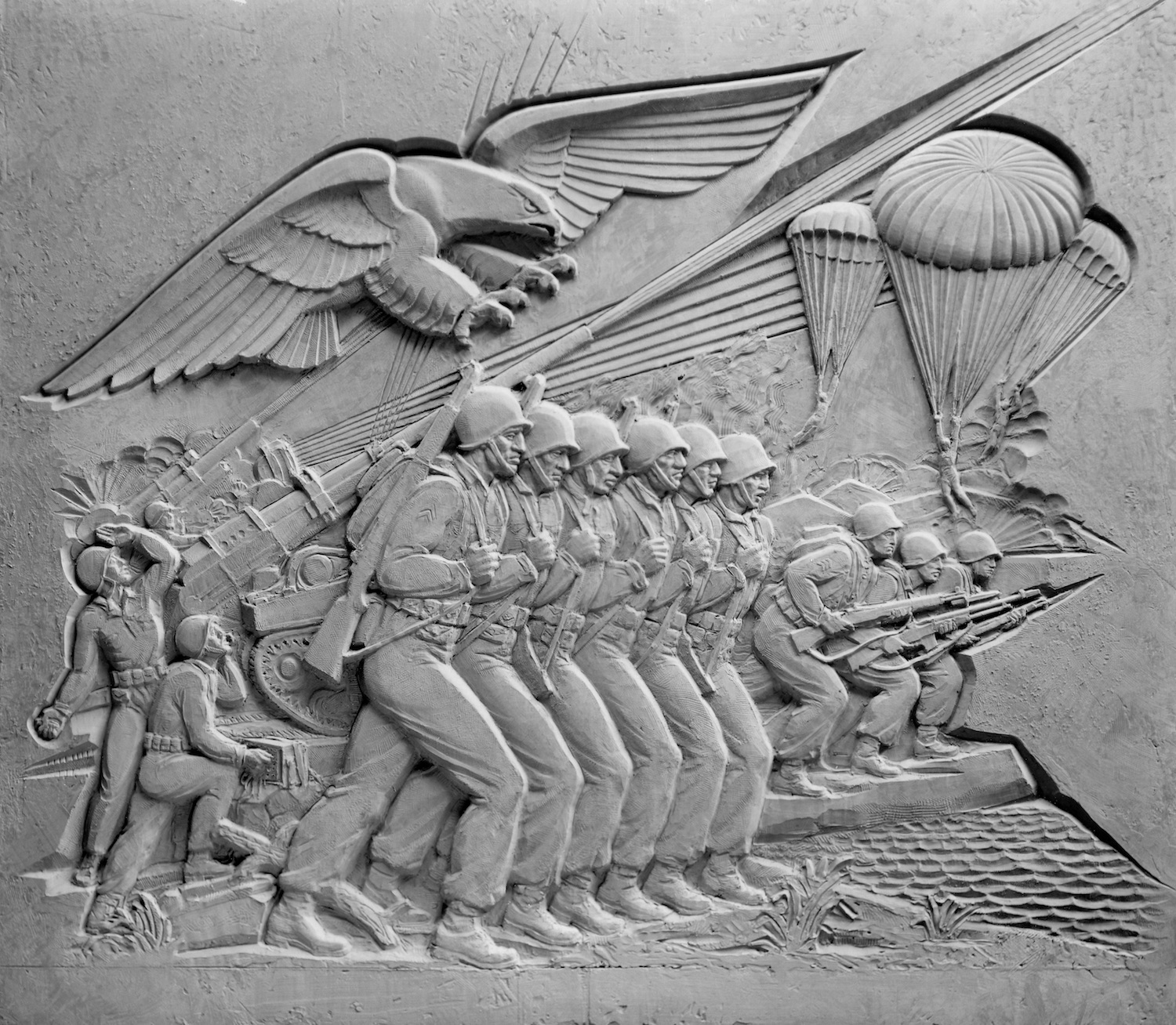

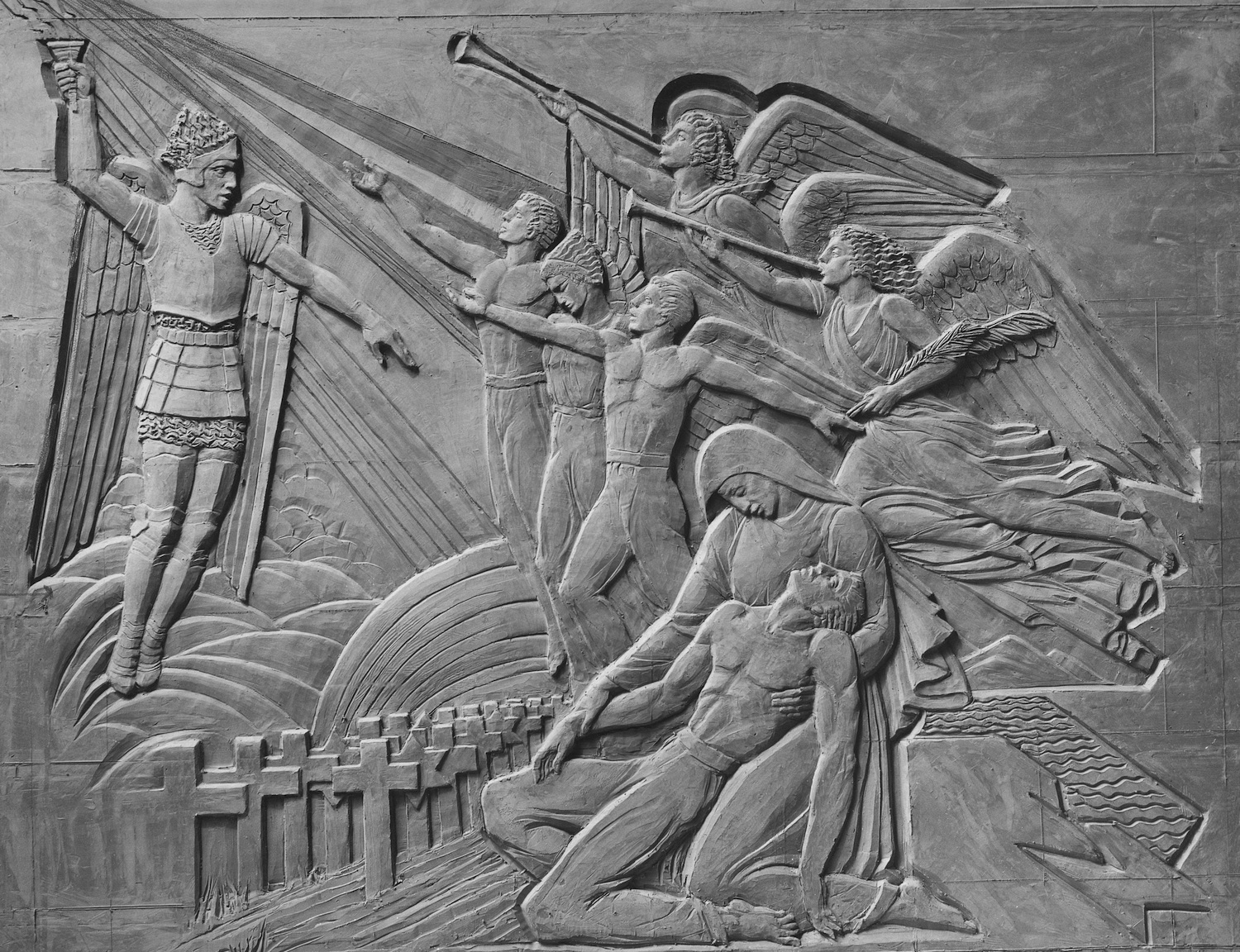

To see how art was used to communicate specific ideas equating American war dead to that of martyrs, consider Malvina Hoffman’s sculptures. She created the bas reliefs eventually carved into the façade of the memorial building located in the Épinal American Cemetery, in Vosges, Lorraine. The south-facing wall bears a large inscription on the attic, taken from Exodus 19:4, reading “I bare you on eagles wings and brought you unto myself.” As the visitor must pass through this structure in order to visit the graves, Hoffman’s bas reliefs are inescapable, and the memorial building acts as a physical threshold, a gateway to the field of headstones.

In the scene on the left part of the façade, a Hoffman bas relief entitled War, a ferocious eagle escorts battling American soldiers, its wingspan providing cover. The composition is arranged in several groups of soldiers. In the center, one group marches with methodic efficiency, the six silhouettes echoing each other with precise patterning. To their right, three men charge with bayonets engaged, and on the right upper corner in the distance, a group of paratroopers hang like marionettes from their parachutes, swooping down in great, arc-like trajectories.

On the left, a man yells into a radio while another energetically throws a grenade towards the enemy. The grenade thrower is assisted by a radioman, both looking up towards the great arc of the cannon of a 90-millimeter anti-aircraft gun. Schematic, directional lines depict guns firing deadly explosions from left to right. The busy scene highlights an organized calm under fire, demonstrating the tireless might of the American military—a formidable noble enemy, and certainly one that would be better cast as an ally.

After completing her research and drawing studies, Hoffman worked in two stages: first, as intaglios (the term for the clay models for the bas-reliefs) and then as the permanent carvings we see today. During the intaglio stage, in May 1949, Hoffman’s work was studied by representatives of the ABMC and another government agency charged with advising the federal government on matters pertaining to the arts and national symbols, the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA). Their discussion was made into a transcript and given to Malvina Hoffman. It is clear that they did not like what they saw and urged her to change her design.

Hoffman’s original design for War arranged a group of marching men displaying only their backs, creating an impersonal and even robotic effect that the CFA, who counted among its members the famed allegorical sculptor Lee Lawrie, in particular, disliked. Whereas Hoffman wished to place emphasis on pattern and line, the ABMC encouraged her to imagine heroic individuals. With the faces barely visible in Hoffman’s original design, this was impossible. In response, Hoffman created a group composed of the most generic of faces, so that each visitor might imagine one “stand-in” identity as the American soldier.

Just exactly how the government was shaping the narrative of the memorial is even more apparent in the story of the creation of the right panel bas relief, Survival of the Spirit, which introduces a glorious death followed immediately by an ascent to heaven. Hoffman’s first study had depicted the fallen soldier’s moment of death and an angel’s lamentation while laying him into a grave, and idea that came from Revelations 7:14, 7:16, and 21:14: “These are they that came out of great tribulation … They shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more … And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes.”

But, during the 1949 evaluation of her proposal, the CFA and the ABMC suggested that the angel figure (the Angel of Life, or Gabriel) be made larger and the dying soldier be made smaller. Hoffman subsequently changed the composition to feature the fallen youth in a Pietà, referencing the traditional pose of the Virgin Mary with the dead body of Jesus on her lap. Hoffman then paired the Pietà format with a sequence showing the fallen American soldier’s rise to heaven, heralded by Gabriel and other angels.

This switch, from a lamentation to a triumphant ascension, underscores how the ABMC and CFA intended to create Christian messages of redemption associated with sacrifice and martyrdom. In this symbolism, the American fallen was a Christ-like figure in his pure nobility.

The government-driven change was also ideological, recasting war trauma as a bloodless experience. This was not a new strategy—political leaders have been justifying war death for centuries. But the application of art, architecture, and landscape design to war commemoration—the phenomenological experience, in other words—is particularly American.

Through Hoffman’s design, the large group of American war graves was reimagined as a regiment of heroes. And with this display of sacrifice of over 5,000 men and women comes an implicit caution to anyone who might pose a threat to world freedom. The power of the United States is demonstrated not only by its soldiers’ sacrifices but also through cemeteries that represent America’s visualized promise to never stop fighting.

Send A Letter To the Editors