Shorn sheep block a path in New Zealand, where the widely-used Bowen method of sheep shearing originated. Courtesy of Cecil Sanders/flickr.

My journey to a vocation as a sheep shearer began in 2007 when I moved to California to take a chance on the man who would, happily, become my husband. I thought a knitting class might be a good way to make new friends.

Then, as now, local food was all the rage, evidenced in crowded farmers markets, whole-animal butcher classes, and field trips on foraging food. I thought local yarn sounded like a good idea, too. “Don’t these same people care about where their clothes came from?” I wondered. Yarn, after all, is the foundation of all fabric, spun to thin thread and then either woven or knit. “Aren’t synthetic fibers at least as bad as a factory-farmed hamburger? Why can I buy sheep’s milk cheese at the weekly farmers market on my street, but not a hat or sweater from the very same animal?” I began searching for answers.

I found many. Most U.S.-grown wool is exported raw, returning in garments labeled only with the country name of the last manufacturing step—as required by trade treaties. On top of that, most U.S. wool and textile weaving mills had closed by the early 1990s. Still another factor is a shortage of sheep shearers: the people most likely to raise sheep breeds that make interesting yarn have trouble finding a shearer, due to the smaller sizes of their flocks. This is because shearers typically make money on volume. At $3 a head, for example, a shearer needs to shear at least 100 sheep per day to make a decent living. And shearers themselves are a dying breed. As Gary Vorderbruggen, one of my shearing instructors, says, the first thing you do to get ready for shearing season is to “call your shearer and see if he’s still alive.”

In May 2013, I attended a beginning sheep shearing school at the University of California Hopland Research and Extension Center, where I got beaten up by sheep for five days straight. By day three, my lip was split, my body was purpled with hoof-shaped bruises, and I had trouble standing up to walk. By day five, I had a dim idea of what I was doing and could shear a few sheep per day.

Shearing is a highly skilled job, a full mind-body experience. Courtesy of Stephany Wilkes.

A classmate took me out on some shearing jobs with him, and though I still don’t know why shearing stuck, it did. Shearers blame “wooly worms” for it, because even we can’t explain why shearing is rather addictive. If nothing else, I knew I preferred an ornery, manure-laden, 250-pound, horned ram over my day job—which was, at the time, in tech—any day of the week.

Since then, I’ve spent much of every January through August in barns loud with the sound of electric shears, wool baling machines, bleating sheep, and sometimes a generator. Shearing is a highly skilled job, a full mind-body experience. To keep all involved injury-free, we must intensely focus on what we’re doing. If we get too caught up in our own worlds, we’ll seriously hurt ourselves and the sheep. I’m constantly watching where my hand is in relation to the shears, if I’ve pulled the sheep’s skin taut enough so I don’t cut it, if my feet are in the right place, and so on.

As I have slogged my way through each back-breaking job, I have learned that sheep shearing looks much the same today as it has for the past two centuries. It’s an American tradition—a highly skilled, journeying trade—that has always relied on crews of immigrant and American workers alike, some of whom descend from earlier generations of Native American, French, Basque, English, Portuguese, and Mexican shepherds.

The tradition of sheep shearing, and the way it survives today, are the result of humans creating wool-growing sheep. Wild sheep, like the American-native Bighorn, shed their wool as they grow it. But domesticated sheep have been bred over the course of 15,000 years to hold onto their wool. We created sheep to reliably grow our clothes in our backyards, year after year, until we were ready to harvest it. Today, wool must be sheared every 6 to 12 months for the good of the sheep.

Skilled shearers are in high demand. By my best estimates, there are currently 350 to 500 actively practicing American sheep shearers, a few dozen of whom are women—not nearly enough to cover 5.23 million head of sheep and lambs in the country. Reduced sheep numbers (down from tens of millions in individual states alone) mean that shearers need to be recruited from other countries on H2-A sheep shearing visas, and shearers like me have to travel farther. I’ve met more than one shearer in his or her 50s or 60s who says they used to hit their numbers for the year by shearing “across the street and down the road.”

The unrelenting physical demands of both shearing and the road life combine to make the shearing community a tightly knit, mutually supportive one. Every shearer is, automatically, each other’s “ride or die,” and it’s palpable. Besides, I enjoy equal pay for the first time: unlike my experience in tech, everyone on a crew is paid the same per-head rate. The only difference is how many sheep each of us shears.

How much does our present-day shearing community in the U.S. resemble that of the past? There is not much documentation, but one historical source is The Flock by writer Mary Austin, published in 1906. In it, she describes the crews and manner of shearing in California during the late 1800s, which feels similar in communal spirit and camaraderie to shearing days today. Austin writes, “each man chose to shear what pleased him … Under the social stimulus they turn out an astonishing number of well-clipped muttons.” Austin quotes a rancher who says that, as of the 1860s, “there were no laborers but” Native Americans, that “Round the half moon of the lower San Joaquin the Mexicans are almost the only shearers to be had,” and describes camps comprised of French, Basque, and American shearers. She describes shearers calling out their tallies and notes she heard once heard a man keep tally in three languages. That strikes me as quintessentially American.

Austin’s book also reflects the nature of sheep shearing today, which crosses a lot of international borders. Because sheep shearers are in high demand all over the world, some shearers come to the U.S. from cultures with their own long, expert traditions in sheep and wool: Peru, Mexico, Uruguay, Australia, and New Zealand. U.S. workers also travel to Australia, New Zealand, and Europe to shear as temporary workers themselves.

The design of the tools we use is another thing that hasn’t changed much in the course of a century. In a 1902 advertisement, a boy operates a similar set-up to the one I use. He cranks the motor, which—via gears and transmission—moves a cutter across a comb. Distance is another part of the craft that hasn’t changed. Sheep still travel great distances, and shearing crews travel even farther to tend to remote flocks—if not quite as far as Austin describes. Today, land in the U.S. is too divided between public and private entities to let flocks roam to the extent they once did. Austin describes a “shearing crew which has begun in the extreme southern end of the [San Joaquin] valley, passes north on the trail of vanishing snows as far as Montana, and picks up the fall shearings, rounding toward home.”

Still, between January 1 and August 30 each year, I typically put 10,000 miles on my car—and I’m lucky, because many of my small-flock jobs are close to home. Iowa-based shearer Alex Moser noted in January 2019 that he puts 45,000 miles on his truck each year, while Michigan-based shearer Tim Wright says he averages about 18,000 to 22,000 miles a year.

Today, pick-up trucks tow the shearing trailer instead of a horse team, but shearers travel and set up to shear much like they always have. After the day’s work is done, shearers may stay in a private camper, truck or tent, as ever. Less often, shearers may share one hotel room nearby. Even an inexpensive one can eat up 15 to 20 percent of a day’s wages, so a hotel room usually means buddying up.

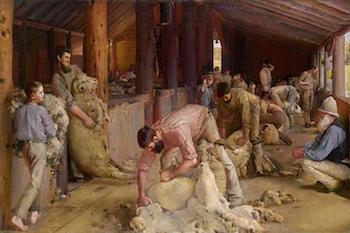

Shearing the rams by painter Tom Roberts, 1890. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Victoria, Felton Bequest Fund.

One thing that has changed is the way we actually shear the sheep. The shearing method we use today is called the Bowen—or New Zealand—method, a shearing dance designed to keep the fleece in one piece and achieve maximum speed and quality work, with a minimum of physical effort. It’s safe for the sheep and gets them out of the experience as quickly as possible. It was invented by brothers Ivan and Godfrey Bowen, and over the last few decades has become standard practice in the world of sheep shearing.

When we use the Bowen method, we put the sheep on its back and make three strokes with the shears down the belly. We cover teats and udders with the hand that isn’t holding the shearing handpiece, so we don’t nick them. Next, we go out the right leg, then back up the same leg. After this, we shear the sheep’s left leg, sinking our fists into the hip socket to straighten the leg out, and then shear the hip haunch (hock) all the way over to the spine.

Each and every movement is carefully choreographed between feet, hands, shears, and sheep. For example, as we shear the sheep’s head, we bend the ear over each eye, to protect the sheep’s eye socket and to see clearly around the ear. Later, to shear the neck, we’ll step forward with our right foot, put it between the sheep’s legs, and push our right knee into the sheep’s chest, which keeps it safely held while we do long strokes to shear the neck. After this, we make long sweeps of the shears down the sheep’s back and sides, which is the fun part; sustained, smooth, fast strokes. Finally, we pull the shears off, release the sheep, and gently pat its rump as a signal that it’s free to stand and go. The sheep pop up between our legs, facing the door, and run off to their flock and food.

Sheep have gotten much larger over the past hundred years, which makes shearing them much more physically demanding. As recently as the 1980s, a 170-pound ewe was considered a big sheep. Now, shearers regularly handle 250- to 300-pound sheep.

I hope I will have work for as long as I can hold my shears and a sheep. We need more natural fibers and sheep for different, complementary reasons: as natural, compostable fiber for the fashion industry, to replace plastic-shedding synthetic fabrics, and for soil health as well. As the climate changes and flooding and soil temperatures increase, we will depend more heavily on sheep and goats that can graze a wide variety of plants and efficiently turn that energy into both fiber and food.

We always need more shearers to join us. Shearers get injured, start families, reduce travel, and retire. I think it’s an underrated, rich, free life. I see the most beautiful parts of the country; I love the sheep and my shearing community; and no two jobs are ever alike.

Send A Letter To the Editors