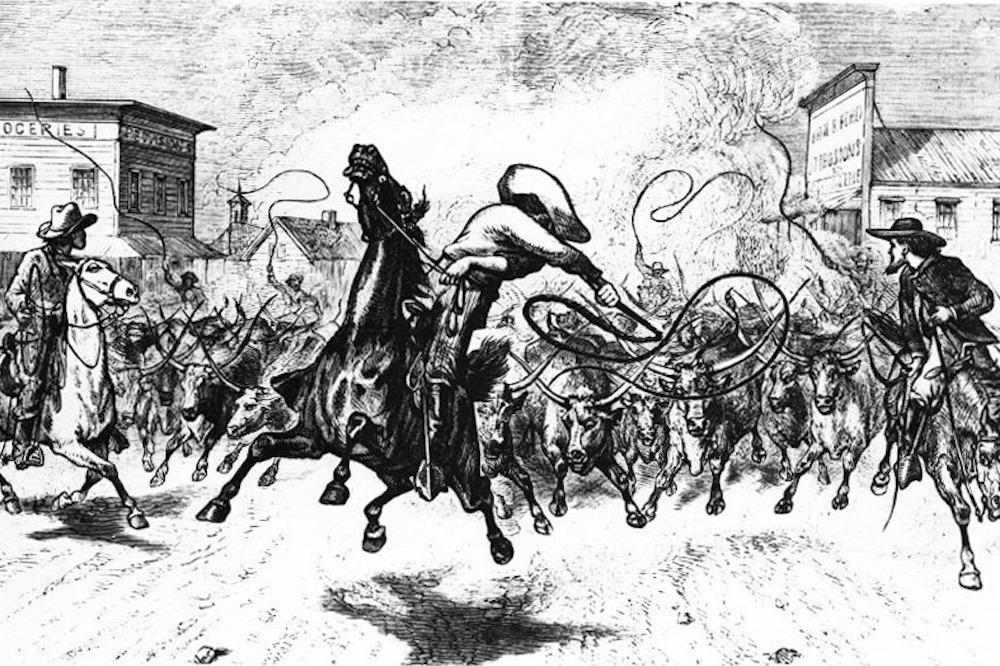

Ranchers drive Texas Longhorns through the streets of Dodge City, Kansas, in a sketch by Edward Rapier, 1878. Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society.

Boasting dozens of windows and a hundred-person dining room, the Drovers Cottage was quite a hotel by the standards of the 19th-century American West. Even more impressive: It managed to be the main attraction of two different towns.

Dovers Cottage was originally built in Abilene, Kansas, during a cattle boom in the late 1860s, when Abilene was the first great railhead connecting the cattle ranches of Texas to the emerging national rail network. But Abilene’s fortunes soon turned—when Ellsworth, Kansas, took its place as the new cattle boomtown.

Ellsworth rose to prominence in 1872 after it embarked on an audacious scheme to attract railroad construction and launched a whisper campaign against Abilene. In the words of one Abilene defender, the situation was “utterly unscrupulous” and “full of low cunning and despicable motives.”

A Santa Fe Train passes through Ellsworth, Kansas, 1867. Photo by Alexander Gardner. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Still, following the herd, the owner of Drovers Cottage moved his hotel, board by board, the 60 miles from Abilene to Ellsworth. The hotel would not prosper for long, though. While tens of thousands of cattle would pass through Ellsworth in 1872, three years later the town was declining just as Abilene had. Cattle trailers and railroads moved on to new towns, like Wichita and Dodge City.

The wrenching boom and bust cycles that roiled 19th-century Kansas cattle towns have much to teach us about how economic development reshapes communities, even today.

The emerging national market for cattle brought new opportunity to towns like Ellsworth, but it also tied their fates to distant economic forces beyond their control. Today, communities still rise and fall with the ebb and flow of global capitalism, as manufacturers make cities compete to host and subsidize new plants, and sports teams threaten to relocate if local leaders don’t hand over generous tax breaks.

Ellsworth’s rise and fall was dictated by the railroads. During the late 1860s and early 1870s, the nation’s rail network was only starting to push toward northern Texas—so Texas ranchers had to trail their herds northward to the nearest rail access points if they wanted to transport cattle to far-off buyers. Kansas towns at the leading edge of railroad construction vied to become hubs that could capture the majority of the cattle trade.

But any of several towns could potentially serve this function; the winners in this contest would be determined by where rail lines were built. A promoter of one town might negotiate with a railroad manager, while competing promoters in nearby towns were doing the exact same thing—with bribes in hand. Another external factor exacerbated the competition: uneven enforcement of quarantines intended to prevent transmission of the cattle disease known as “Texas Fever.” Town leaders, balking at the expense of quarantine compliance, often pushed state officials to enforce rival towns’ compliance while asking that a blind eye be turned to their own potential violations.

Thus, Ellsworth captured the cattle trade in early 1872 by attracting the Kansas Pacific Railway and pushing for tougher enforcement of cattle quarantines in Abilene. But rail lines soon reached southward to Wichita, and within a couple of years Wichita captured the trade from Ellsworth—until enforcement of quarantines in Wichita made Dodge City, far to the west, the newest Kansas cattle shipping center. Eventually, the railroads reached Texas, increased settlement in Kansas made quarantines unavoidable, and Kansas cattle towns all entered decline. So ended a frenzy in which an individual town might win in the short-term, but all towns, eventually, were set to lose.

That competition between towns sparked tension within communities as well. Ellsworth had vocal supporters of the cattle trade (merchants and the editor of the local paper) and passionate critics—especially local farmers. Cattle were hungry when they reached the area and could eat local fields bare or spread disease to local livestock.

Critics also contended that the cattle trade enriched a few merchants at the expense of the region’s long-term residents. One angry Ellsworth citizen asked, “What safeguard can be set up to protect … from the encroachments of men whose souls are wrapped up in the almighty dollar; men whose highest and only object is to increase their wealth even if it destroys the prospects of a whole community?”

Such criticism echoes today in the fight over the location of Amazon’s second headquarters.

At first, Amazon was able to get American cities to bid against each other to host the company, garnering offers of over $1 billion in tax breaks and other incentives. The company ultimately chose two locations—northern Virginia just outside Washington, D.C., and in the New York City borough of Queens. But in New York there was a backlash, as community leaders argued that an Amazon facility would benefit rich residents of the city while leaving Queens’ poor behind. In this way, by entering a community, a business can heighten pre-existing divisions and precipitate local power struggles. Amazon eventually had to pull out of the Queens deal.

Can communities embrace national markets while protecting local interests? The history of Ellsworth, Kansas, suggests that economic development contests pose challenges too big for any individual place to solve for itself.

In 1875, a night watchman in Ellsworth spotted a small light coming from the now-neglected Drovers Cottage. When he went to investigate, he discovered a fire in the hotel. The blaze was extinguished, but residents’ relief turned to outrage when they found oil-soaked mattresses in a backroom and realized it had been attempted arson. Suspicion fell on the hotel’s proprietor, who soon fled the town. It would be the most dramatic example of a general trend: merchants were leaving Ellsworth in search of fortunes elsewhere.

Ellsworth’s rise and decline unfolded over less than 10 years. It was not as dramatic—nor painful—as the 20th-century ascent and decline of places like Detroit, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana. But the scale of the business briefly centered in Ellsworth—hundreds of residents, hundreds of thousands of incoming cattle—and the speed of the tiny town’s changing fortunes offer an enduring lesson: When small communities are pitted against each other, or made subject to distant markets, only larger government entities—state or federal—can limit ruinous competition.

Send A Letter To the Editors