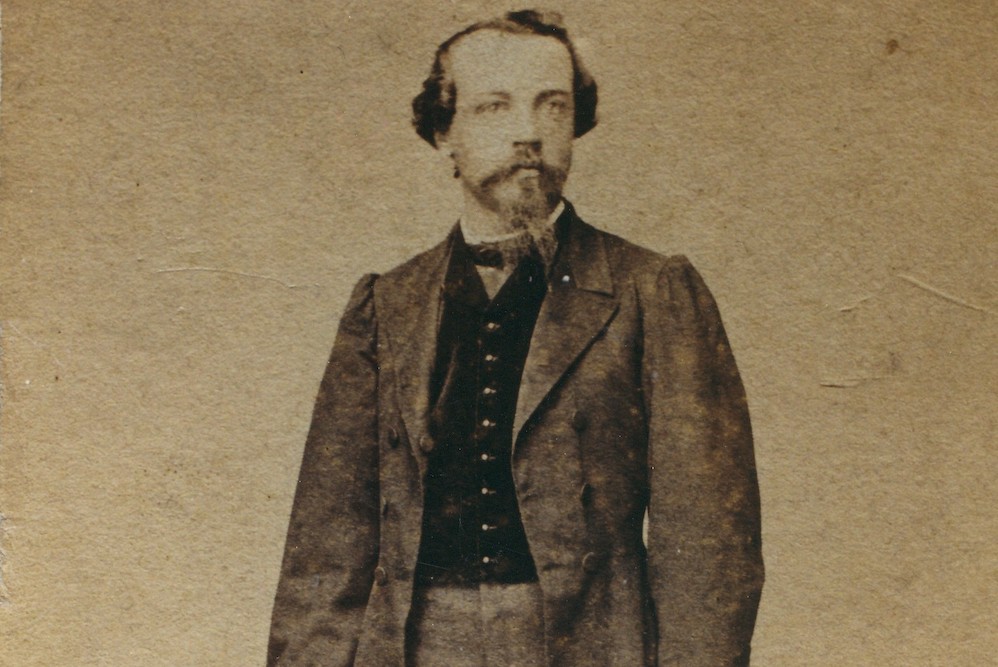

A photo of Arnold Bertonneau, taken around 1880. Bertonneau and other Creole activists fought racism by challenging the very concept of race itself. Courtesy of Thomas Bertonneau/The Orthosphere.

It took years of research for me to track down a photograph of the mysterious New Orleanian E. Arnold Bertonneau. Born in 1834, this Civil War-era civil rights pioneer was famous in his day but somehow has disappeared from the national consciousness. In 1864, Bertonneau lobbied President Lincoln in the White House for African American voting rights. In 1877, he filed the first-ever federal case challenging school segregation, Bertonneau vs. Board of Directors of City Schools, on behalf of his two school-age sons, who had been excluded from a whites-only school. Yet today, Bertonneau’s portrait hangs not in the Smithsonian but sits instead in the out-of-the-way upstate New York home of his great-grandson.

Finally coming face-to-face with Bertonneau’s image, I was shocked. I had been reading about Bertonneau for book research. But while Bertonneau fought valiantly for the rights of black Americans, he didn’t look “black” himself. In the photo, his skin was fair, his eyes were light, and his hair was wavy. In contemporary America he might read as Latino, with a complexion somewhere on the spectrum between Pope Francis pale and Marco Rubio tan. Looking at the late great Bertonneau reminded me that the way passersby perceive a stranger’s race on the streets of America doesn’t necessarily match their actual background. Indeed, one’s own ethnic background may not even be what one assumes it is—as genetic testing has recently made clear to millions of Americans.

The leading civil rights litigants of the Reconstruction era, including Bertonneau, lived these complex racial realities—and it led them to challenge racism by challenging the concept of race itself. Most were openly mixed-race Creoles from New Orleans with roots in both Africa and Europe. This gave them a piercing perspective on American white supremacy and a unique legal arsenal for attacking it.

The most famous civil rights plaintiff of them all, Homer Plessy, who challenged railcar segregation at the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896, was described in the African American New Orleans Crusader newspaper as being “as white as the average white Southerner.” To launch his case, he had had to out himself to the train conductor as mixed-race to get ejected from the whites-only car. Plessy’s ethnic background was estimated to be seven-eighths European and one-eighth African but it was impossible to pin down for sure. That was the whole point. As Plessy’s lawyers asked the Supreme Court justices, “Is not the question of race … very often impossible of determination?” Plessy’s case was an attempt to resist not merely segregation but binary racial labels like “white” and “colored” altogether.

It was only after Plessy, Bertonneau, and the other leaders of the first civil rights movement had been defeated—and indeed because of their defeat—that the black-white binary solidified. Even on the Census, multiracial options dwindled and then died out. Tellingly, on the 1910 Census, Homer Plessy was black but, in 1920, white.

These early Creole civil rights activists who fought against the constricting racial categories of “black” or “white” defined themselves not by color but by culture—much as Latinos in the U.S. do today. Creoles came in every shade and had no pretense to racial purity. What bound the community together was their linguistic roots in a Romance language—French and its Caribbean Kreyol off-shoots—and their Mediterranean-influenced mindset.

Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, as Latin American Nouvelle-Orléans/Nueva Orleans was turned into Anglo-American New Orleans, the Creole community was racialized by outsiders. Anglo-Americans, who were wary of influential free-born Creoles and who were increasingly making “whiteness” a prerequisite for citizenship, obsessed over who among the Creoles had family-tree roots in African soil. The Anglo-Americans began revoking rights, including suffrage, on the murky basis of “race.” Soon after the purchase, they passed an “anti-miscegenation” law requiring whites to marry whites, blacks to marry blacks, and biracial people to marry one another.

Activists like Bertonneau and Plessy, who descended from this third group, fought against all racial categorizations. They were skeptical of the Anglos’ concept of race and their arrogant presumption to assign it on sight. After all, Plessy had had to explicitly tell the train conductor that he was mixed-race to launch his test case.

For nearly 30 years, Creole activists brought a series of cases that needled the Anglo-Americans’ binary view of race. This legal tradition was launched at the height of Radical Reconstruction when the light-skinned newly elected Orleans Parish sheriff, Charles St. Albin Sauvinet, was refused a drink in a French Quarter bar in 1870 and responded by suing for “violation of his civil rights.” In court, the Creole Sauvinet explained that his roots were in the Caribbean, where race was no black-or-white matter. “Whether I am a colored man or not is a matter I myself do not know,” he told the court. And he pointed out that no one could know anyone’s race for sure. Of his two drinking buddies, he remarked, “Finnegan and Conklin who were with me are said to be white men. I do not know. To all appearances they are.” But, of course, as Sherriff Sauvinet himself proved, you couldn’t necessarily ascertain people’s backgrounds by sight.

Sauvinet’s line of argument was seconded by Creole civil rights plaintiff Josephine DeCuir in her challenge to riverboat segregation. In 1872, she’d bought a first-class “ladies’ cabin” ticket for a journey upriver from New Orleans only to be asked to move to the inferior “colored cabin.” The ship’s crew cuttingly referred that section as “the Freedman’s Bureau,” which DeCuir took as a grave insult since she’d been born free into a wealthy slave-holding family. In court, DeCuir, who had roots on the European, African, and North American continents, was described as being the color of a “law book.” To problematize the whole concept of race for the jury, her attorney called to the stand a light-skinned French Quarter resident of Caribbean descent, one Mr. Duconge. In New Orleans, where his Creole heritage was widely known, Duconge explained, he was considered a person of color but in the rest of America, where he was a stranger, he was considered a white man. Hoping to show the jury how absurd the American racial system looked—and, indeed, still looks—to the rest of the world, he offered the statement: “the difference between a white man and a colored man is that the colored man has a darker face than the white man, but you can find a quantity of colored men reputed to be colored men who have white faces.”

Creoles then, like Latinos now, accepted that in the New World—in the U.S. no less than the Caribbean and Latin America—people from different continents have been mixing for centuries. Ultimately, in this view, New World people have become a race unto ourselves—referred to as la raza in Spanish. But Anglo-Americans rejected this reality by engaging in the dastardly fool’s errand of retroactively sorting New World people back out into definitive races, a practice that continues to this day.

Unfortunately, the brilliant Creole legal strategy to challenge racism by challenging race did not win in its time. While Sheriff Sauvinet’s civil rights victory was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, the justices overturned DeCuir’s state court victory and Homer Plessy lost his precedent-setting case 7-to-1.

Learning of their defeat, the Creole Citizens’ Committee that had planned Plessy’s civil disobedience and funded his suit put out a statement: “Notwithstanding this decision … we … still believe that we were right.” Indeed, they were. The Supreme Court could permit the states to draw stark lines between black and white but that didn’t make actual Americans any less mixed.

An older Cuban-born gentleman illustrated this point precisely when he raised his hand after I presented at the Miami Book Fair last November. Recounting his introduction to race in America, he explained that he’d moved to Miami as an 8-year-old boy, in 1960, and at the neighborhood supermarket encountered his first segregated water fountains. Florida had lived under Jim Crow for more than half a century but to the boy it was brand new. Flummoxed, he asked his mother which fountain he should drink from. To the child, the people on the streets of Florida with their full range of skin tones didn’t look much different from the people on the streets of Cuba. But while Cubans acknowledged that they had mixed roots on different continents and thought of themselves, even in the same families, as lighter or darker, the Americans insisted that everyone was distinctly either “white” or “colored.” While Cubans considered “Cuban” to be an ethnicity, Americans refused to see “American” that way—even though they too were a New World melting-pot society.

On his mother’s advice, the boy chose the whites-only water-fountain—after all, he was light-skinned and it was clearly the superior appliance. His decision echoed E. Arnold Bertonneau’s in the previous century. After losing his federal case challenging school segregation and the racial binary, Bertonneau moved out to California and he, too, became “white.”

Americans long ago abolished the segregated water fountains but the binary racial mindset survives both in the American psyche and in American outcomes in health, wealth, education, and criminal justice. But the Latino concept of la raza has the potential to again take up the torch of challenging American racism by challenging the idea of race itself. Through this lens, America is not a society of warring tribes but a dysfunctional family. Warring tribes can only make peace treaties; dysfunctional families are better adept to reconcile and heal. At the dawn of Jim Crow, W.E.B. DuBois observed, “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line.” The question of the 21st century may be whether we continue to see ourselves divided by race or unified as la raza.

Send A Letter To the Editors