In 1920, in a small town outside Turin, Italy, 17-year-old Luigi De Michelis was everything his middle-class parents could have asked for. His teachers liked him, which was important to his father, a teacher. His priest liked him, which was important to his mother, who wrote Catholic children’s books.

But soon Luigi started following the news a little too avidly. Then he started going to meetings on the sly. Suddenly the De Michelis’ good boy was more interested in the man the newspapers called “Comandante” than in the approval of family and teachers. Before his parents realized what was happening, Luigi ran away from home, without finishing high school, to join the movement that had won his heart and mind.

Late in 1920, Luigi sent a letter home to prepare his parents for the imminent reckoning, an armed clash between Italian nationalists (of which Luigi was one) and the Kingdom of Italy’s army, a battle which would come to be called “The Christmas of Blood.” Luigi warned: “Soon there will be battle, maybe soon I shall be no more. Console yourselves in thinking that I died for the purest of Causes …”

How does populist, political charisma change the world and how can we hold it in check? The story of how the De Michelis family lost hold of a child—the history surrounding “the Christmas of Blood”—offers enduring answers to those questions.

Charismatic, populist politicians can have the pull of a cult. The Comandante to whom Luigi was in thrall was not Mussolini, but his precursor, Gabriele D’Annunzio, who was the most famous living Italian in 1920. By the end of World War I, D’Annunzio had created a craze around his own personality in ways only a much-loved celebrity can.

Before World War I, D’Annunzio had been Italy’s most revered decadent poet and womanizer. During the war, at 52 years of age, he enlisted as Italy’s oldest officer volunteer. He flew airplanes, manned ships, and screamed from the trenches, everywhere using his prominence to campaign for Italy’s military cause. After the war, he was the most vocal proponent of Italian territorial expansion.

Mussolini would echo D’Annunzio’s calls, though the two did not get along, agreeing about little beside Italy’s greatness and the feebleness of its government. While Mussolini busily recruited thugs to build his fascist party, D’Annunzio used his far greater fame to stage huge rallies and flood the media with his audacious and emotionally manipulative snubbing of traditional state authority.

D’Annunzio created stirs by combining shock and empathy. He could quote Dante and then call Italy’s prime minister a “shithead.” An elegant dandy, he nevertheless presented himself as “one of the guys,” determined to vindicate those who felt cheated by the state and the world at large. Nice middle-class boys like Luigi hadn’t been cheated, of course, but they responded to the daring of saying what one shouldn’t and to a cause that promised to prevent corrupt bureaucracy from keeping Italy from its destined greatness.

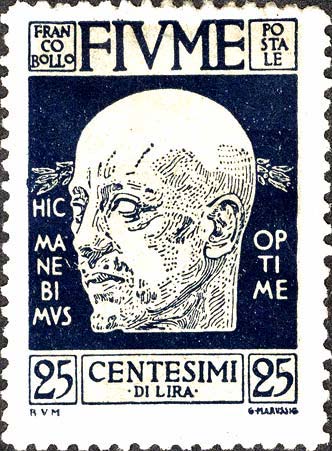

How would Italy achieve that greatness? What was the cause that Luigi was prepared to die for? The last line of Luigi’s letter to his parents makes this clear: “Stay safe, your son salutes you, declaring himself above all ashamed of being Italian, that he no longer wants to be Italian, and from now on is Fiumian. Goodbye, Luigi.”

The reference to “Fiumian” is now obscure, but then was a rallying cry for Italian territorial expansion. Fiume, today known by its Croatian name Rijeka, was a multiethnic port town located in the northeastern Adriatic. Before 1918, it was a semi-independent city-state within the Hungarian half of the Habsburg monarchy. Most Fiumians (unlike Luigi) did not identify as mother-tongue Italians and most were multi-lingual. Significant swathes of Fiumians declared their mother-tongue as something other than Italian—26 percent Croatian, 13 percent Hungarian, 5 percent Slovene, 5 percent German.

This diversity did not interest D’Annunzio and his followers. Instead, they saw Fiume as filled with Italians and as a target—a place they could usurp to make Italy great again.

Fiume seemed ripe for usurpation because of the political fallout at the end of World War I. Before the war, almost 300 million Europeans (including Fiumians) lived within a continental empire, whether German, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, or Ottoman. When all these empires were dissolved in 1918, new countries were created out of their territories, with others expanding to absorb any lands they could get. Under the leadership of the victorious Entente powers, the 1919 Paris Peace talks became a squabbling ground over which states would get what.

Little Fiume turned into one of the biggest headaches that Paris diplomats tried to solve because the town’s Italian-nationalist leadership declared itself diplomatically and legally independent now that its empire was gone (citing their long-standing city-state semi-independence). This wasn’t the only problem. They also insisted that their new independence gave them the right to annex themselves to Italy.

Paris Peace diplomats, with the American president Woodrow Wilson in the forefront, repeatedly rebuffed attempts to annex Fiume to Italy; they made free-trade arguments against giving Italy a full monopoly over the Adriatic and pointed out that at least half the town didn’t consider itself Italian.

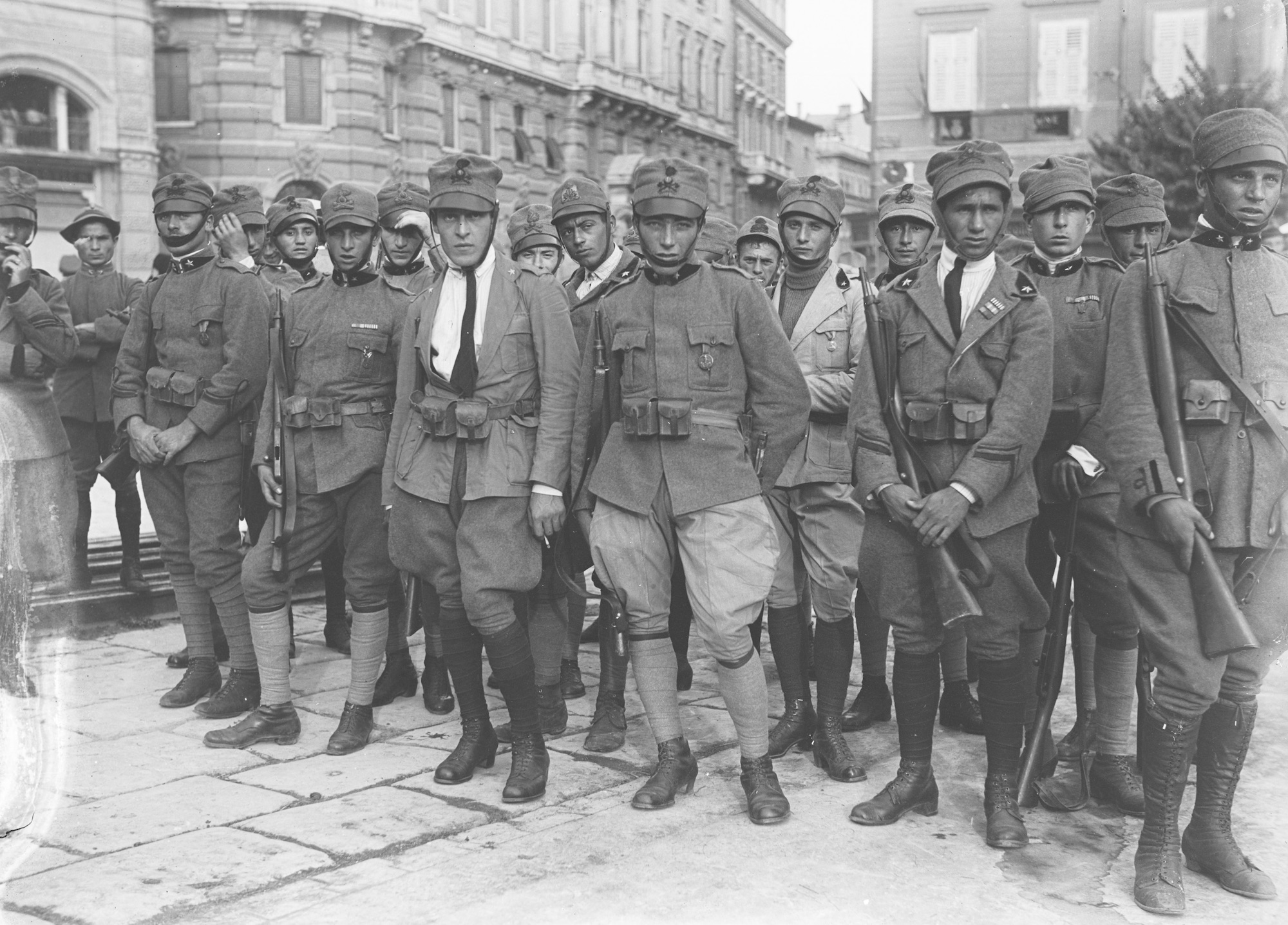

D’Annunzio soon became the most prominent critic of this stance, proclaiming that Wilson was trying to “mutilate” Italy’s WWI victory by denying its rightly earned dominance over the Adriatic. For months, D’Annunzio staged call-and-response rallies filled with lies to push for Italy’s control of the Adriatic and with xenophobic images against “Slavs.” In September 1919, D’Annunzio and his crew stopped just talking and decided to take Fiume.

D’Annunzio and his followers chose Fiume over other Adriatic hotspots because Fiume’s leadership invited them in. So, to the sound of church bells and without a shot fired, they entered Fiume and proclaimed it part of Italy, regardless of what the stuffed shirts in Paris, Rome, Belgrade, or Washington, D.C., said. This unsanctioned seizure of the town was titillating, and newspapers the world over covered it. Luigi was among those desperate to be part of this spectacular Fiume story.

D’Annunzio and his crew expected their de facto annexation of Fiume to Italy to be authorized within a few weeks’ time. They guessed wrong. Month after month, they marched around town proclaiming their endless motto of annexation to “Italy or death!” but no heads of state were willing to recognize their fait accompli.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Fiumians suffered the realities of what it meant to be a state gone rogue from the global order. Counterfeiting went into overdrive, with 60 percent of Fiume’s money supply falsified and no big state infrastructure available to crack down and stabilize. Law codes written in imperial times were patched over to make them look and sound Italian, but everyone was confused about what the real rules were.

Unsure where Fiume would eventually land on the geopolitical map, city policemen refused to follow orders to register their own nationality, even though they all spoke Italian. Croatian- and Hungarian-speaking schoolteachers were ordered to take Italian courses in their free time to make sure the proclamations of Fiume’s Italianness rang truer. Translators were hired to hide the fact that many bureaucrats and businesses still functioned more within a multilingual Central European mindset than a monolingual Italian one. And every day, everyone got poorer and hungrier as D’Annunzio’s Fiume grew more diplomatically isolated.

The Fiume fiasco lasted 15 months before the Kingdom of Italy and the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (soon to be known as Yugoslavia) agreed that the only way to end this destabilizing interregnum was to make Fiume an independent city-state. That meant that neither nation-state would get it. D’Annunzio refused to recognize the treaty; he still demanded annexation to “Italy or death!” Italy threatened military action. D’Annunzio’s reply: Bring it.

Eventually, Italy decided to attack, but—to avoid attention—waited until Christmas 1920, when newspaper readership was at its lowest. (Italian politicians had learned the hard way that D’Annunzio was catnip to the media).

Before the first shots were fired, D’Annunzio proved again why the press could never get enough of him. He dubbed Italy’s attack a fratricidal “Christmas of Blood,” a name that has stuck. He might have won the media war, but there was no way the Italian army would lose the real one. The town was bombed; Italian soldiers invaded. D’Annunzio’s followers blew things up and shot at the arriving soldiers. Fortunately, hardly any soldiers died, though D’Annunzio often lied about this, inflating the numbers of casualties on both sides. Even fewer civilians perished, mostly because they hid in their homes waiting for the madness to end.

By New Year’s Eve, Fiumian statesmen had convinced D’Annunzio to surrender and recognize the treaty. Italy had won, but all sides felt they had lost. Italy was regularly demonized for perpetrating a fratricidal attack in a holy season. D’Annunzio was ridiculed for not surrendering in the first place.

Like most of his comrades, Luigi survived and returned home hungover (literally and figuratively) from the entire experience. He spent the next years working to catch up on the middle-class plans his parents had always had for him. With his “Fiumian” identity shed, he finished university, joined the Fascist party (like millions of others), and became a respected pharmacist in a seaside town north of Rome.

The future for real Fiumians was less easy to rehabilitate, however. They were left living in the material and political rubble of a “Christmas of Blood” most had hid from and few had supported.

None of this should have happened. That it did still produces important questions. Why would Italian nationalists go to war against their own Italian nation-state? Why would nice boys like Luigi drop everything to join them? And how and why did a town filled with so many non-Italians put up with all these D’Annunzio converts in their desperate mission to make Fiume part of “Italy or death”?

Historians of charismatic politics have written hundreds of books trying to answer the first two questions; most ignore the last one. Many of their answers are psychological at their core; they investigate how people got brainwashed into thinking that “justice” for Italy would come from taking over a town few Italians had ever heard of. These histories are frightening because they make it seem that the right combination of charisma, anger, and a tendentious media will convince people to do things they would never have thought acceptable before.

It’s easy to see how this lesson relates to Mussolini’s rise, but it’s also frighteningly relevant right now, in the United States and around the world.

For me, the scariest part of the power of charismatic populism is different, though. I’m most afraid of the very last line of Luigi’s letter, where he identifies himself as “Fiumian.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth. In his diary and letters, Luigi admitted often how foreign Fiume was. But he and the rest of D’Annunzio’s entourage successfully convinced themselves, much of the newspaper-reading world, and most historians that they—aggressive outsiders—were everything and everyone, that they were Fiume. As this entire “Christmas of Blood” narrative shows, charismatic populist politics don’t merely convince us to run away from home or leave behind our family and country. They have the power to erase everything outside those politics, including reality itself.

That’s why, in confronting populism and charismatic leaders, we must focus more on the world erased than the world they hoped to impose. We need more study of how wrong the brainwashed thinking was, instead of focusing on its appeal to people. Otherwise, we risk replicating precisely this nefarious vision: that the leader and his followers are all the world worth knowing about.

That’s also why history matters. It’s important to replace prepackaged “extraordinary” stories like the “Christmas of Blood” with the realities that produced a “Christmas of Rubble.” And it’s important to recognize that defeating charisma politics requires taking away its stage or balcony, so that people can see all the drama, troubles, hope, and failures of the big multiethnic world that the D’Annunzios, Mussolinis, and Trumps have worked so hard to overshadow.

Send A Letter To the Editors