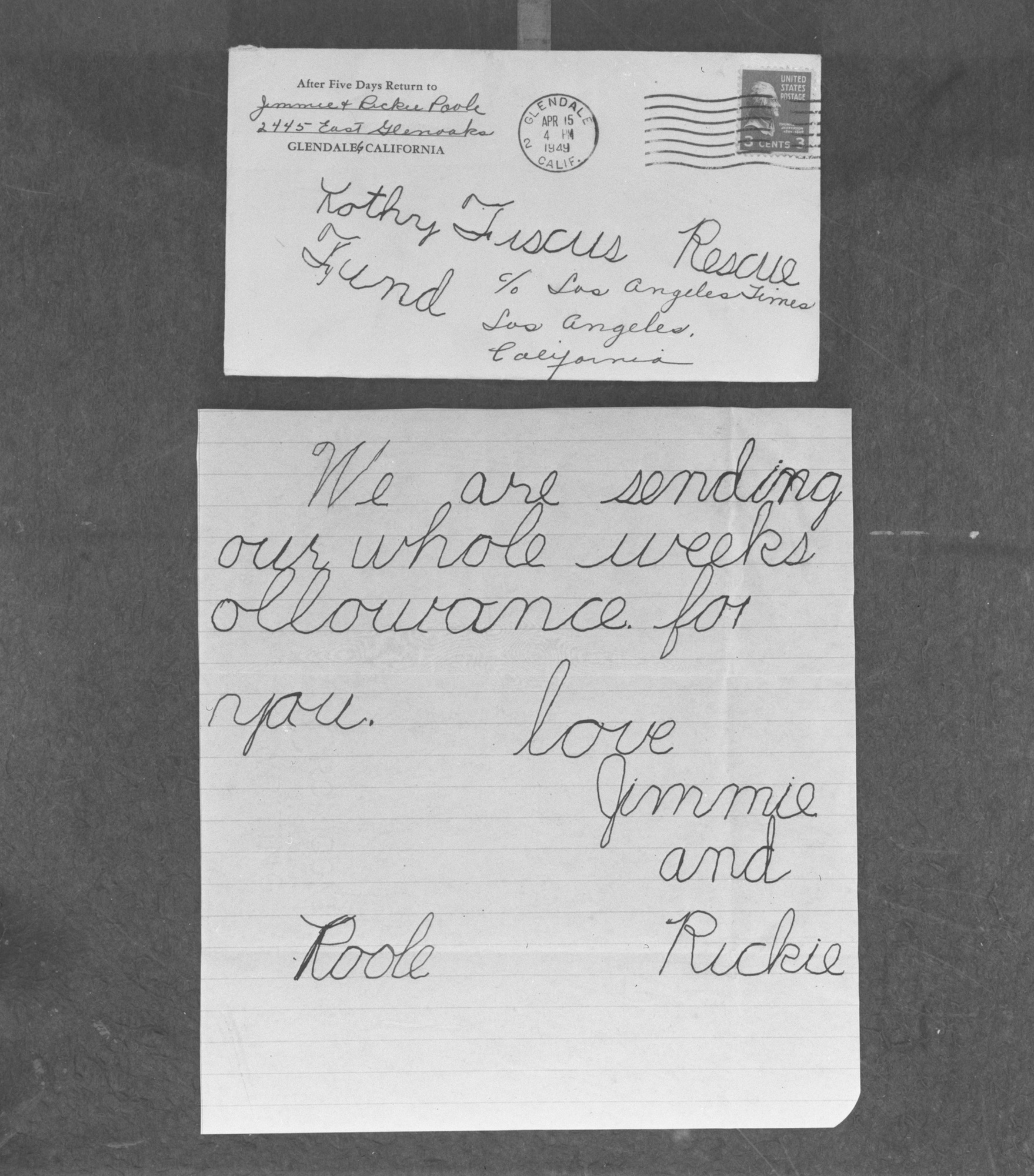

The Kathy Fiscus Tragedy Transfixed the World. Seven Decades Later, I Can’t Let It Go

A California Historian Can’t Shake His Obsession With the 1949 Death That Became the First Live, Breaking News TV Spectacle

I can walk from my home to the area where Alice Fiscus stood in the kitchen chatting with her sister Jeanette on that fateful late afternoon of April 8, 1949. The landscape is changed now. But with luck, a good map, and a historic photograph, I can get within ten feet of where Alice looked out that window and first realized that her youngest child had disappeared. I have tried it before, and I feel like trying it again as I write this. Right there, at the mouth of an old abandoned well, live television news began, and worldwide media changed forever.

How many times have I thought of the moment when idle banter between the two sisters turned to confused silence, then concern, then fear? Hundreds, easily, probably thousands. I have wondered over and over again what Alice said to her sister as the sun cast its waning light across that little kitchen. “Where did Kathy go?” “Where’s Kathy?” “Now where has Kathy run off to?”

As a historian, my job is to try to assemble the fragile, fragmentary puzzle pieces of the past. Establish chronology, narrate change, assess cause and effect: bring the past into conversation with the present. It is endlessly fascinating work—a strange, heady mix of expertise and fool’s errand. But I have never worked on a project that has occupied my thoughts or my dreams in any way close to the way the Fiscus story has.

What is it about this story, of a tragic death from seven decades ago, that I cannot shake? It is a type of haunting. Proximity surely has something to do with this story’s hold on me. I study the American West, especially of California, and this is fundamentally a California story—although it very quickly reverberated from the town of San Marino across the nation and the world. Its California-ness feels very close to me, and to what I think and write about in my work. There is also proximity by way of chronology. I tend to work in the 19th and 20th centuries. Those hundred years between the Civil War and my birth in 1962 feel familiar. I spend a lot of time contemplating them.

Compared to most of my work, this episode feels nearly contemporary; 1949 is only 13 years before I was born. I know plenty of people born well before 1949. It just wasn’t that long ago. The sheer closeness of the events in this story, in both time and place, is part of what intrigues me.

But who am I kidding? “Intrigues me” is not the half of it. This story obsesses me. The roots and persistence of that obsession raise questions that I cannot easily answer.

Fatherhood is part of it. My wife and I have two children. Our son, John, is in high school. His sister, Helen, is a university student. They are young adults, but I still worry about their safety as they venture out and about—driving, cycling, camping, rock climbing—just being who they are and doing what they do.

On a weekend afternoon more than a decade ago, I asked my daughter, who was 7 or 8 at the time, if she would help me with a project. Could she cut a circle from a sheet of construction paper? Helen said yes. She liked craft projects with paper and scissors. I told her that the circle needed to be 14 inches in diameter, and I held my hands that far apart.

Helen went out back to the playroom and returned with a sheaf of construction paper. She sat on the floor of our living room, right by the big front window. She tore out a purple piece of paper and quickly figured out how to complete her task, maybe with a little help. She marked two cardinal points on the paper north and south, fourteen inches apart. Then two more, east and west, likewise fourteen inches apart. With a pen, she drew a circle connecting all four points. She then carefully cut the circle from the paper and held it up. “Like this?”

I remember the moment as if it were yesterday. From where I write this, I can look to our living room where Helen proudly held up the purple circle in the light of that big window.

I caught my breath. It is one thing to know how small 14 inches is. It is something else entirely to see it, especially once we had taped it to the hardwood floor.

The circle is the shape and diameter of the old well that 3-year-old Kathy Fiscus fell into late that April afternoon in 1949.

A tube of rusted metal, just over a foot in diameter. A circle of purple construction paper a lifetime later.

Send A Letter To the Editors