Mitsuye Endo participated in a landmark Supreme Court case challenging the right of the government to hold citizens in concentration camps like Topaz. Digital Image © 2012 Utah State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved.

Since 2017, a famous black-and-white photo has stayed with me: a young Japanese American woman sitting in front of a typewriter, hands poised in the home position, looking over her left shoulder and directing a close-lipped smile at the camera.

The photograph depicts Mitsuye Endo. At the time it was taken, circa 1944, she was incarcerated in an American concentration camp in Topaz, Utah. Of the four young Nisei—American-born children of Japanese immigrants—who contested the grounds of their incarceration at the Supreme Court, Endo was the only one who won her case, and unanimously at that.

As a daughter, granddaughter, and niece of Japanese American camp survivors, I have been reading about my community’s wartime incarceration for most of my life. But while Endo’s case is familiar to those in legal circles and Japanese American studies, her story is largely unknown by the general public. Why, I wondered, did I know so little about Endo herself, and why didn’t everyone know more about the case that helped lead to the closing of the concentration camps for all Japanese Americans?

When I was hired as the only woman on a creative team of four to create a graphic novel on one of the most important stories in the history of Japanese America, I knew pretty quickly that I wanted to tell Endo’s story. The graphic novel, which became We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration, pushes back against a dominant narrative about the camps: that Japanese Americans not only went there willingly, but stayed there willingly in order to prove their loyalty to the United States. We wanted to share a story of Japanese American resistance: not to the initial eviction, but to the unjust and unconstitutional conditions of their incarceration.

The widely known exceptions to the narrative of Japanese American compliance remain overwhelmingly male: the principled stances of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui, who took their cases to the Supreme Court alongside Endo; the collective organizing behind the Heart Mountain draft resisters, who refused to go from the camp to the U.S. Army; and John Okada’s novel, No-No Boy. Thanks to the work of scholar Mira Shimabukuro, we learned more about—and dramatized the story of—the Issei women who were important to the draft resistance movement. By also featuring a Nisei woman, I hoped to deepen the narratives about who was resisting, and how.

Layers of silence have veiled Endo and her case for years. As a scholar of Japanese American women’s literature, though, I know that silence has multiple meanings. Thanks to writers like Joy Kogawa and scholars like King-Kok Cheung and Traise Yamamoto, I know that silence can mean strength. It can mean a guarding of privacy. It can also mean refusal to speak on someone else’s terms.

And without question, Endo wrapped a layer of silence around herself and her case which proved that “concededly loyal” citizens could not be infinitely detained. She only gave two painfully short interviews about her case, one in 1976 and the other for John Tateishi’s 1984 oral history collection, And Justice For All. Her 2019 “Overlooked No Longer” New York Times obituary says that she spoke about her experiences with her children when asked, but they did not know about her case or its significance for years. She did not participate in the testimonies of the 1970s and 1980s redress movement for reparations. As historian Greg Robinson notes, “[Endo] represents an unusual case of heroism—a hero both self-effacing and effaced by others.”

In Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases, lawyer Peter Irons referred to Endo as “the recruit.” Compared with his other labels for the Japanese American litigants (Hirabayashi was “the moralist,” Korematsu “the loner” and Yasui “the legalist”), it’s a label accompanied oddly with a comparison to Issei picture brides: an arrangement based a gendered exchange of images. This label seems to have followed Endo’s case for some time, but it masks her own sense of justice and obscures the nature of the decisions she had to make.

Eleven years after Endo’s death, in 2017, I began working with my co-author, Frank Abe, to tell her story. Frank, who has been working on camp history for over forty years, was concerned that we wouldn’t find what we needed to tell her story, and it took us close to two years of research and interviews. Asian Americans Advancing Justice, who had produced a short posthumous documentary honoring Endo, connected me with her children. Eventually Frank flew out to the Midwest to meet them. There he made his own discoveries about Endo’s personality, including the confirmation of his hunch that Endo, like many Nisei, went by an “American” nickname, “Mitzi.”

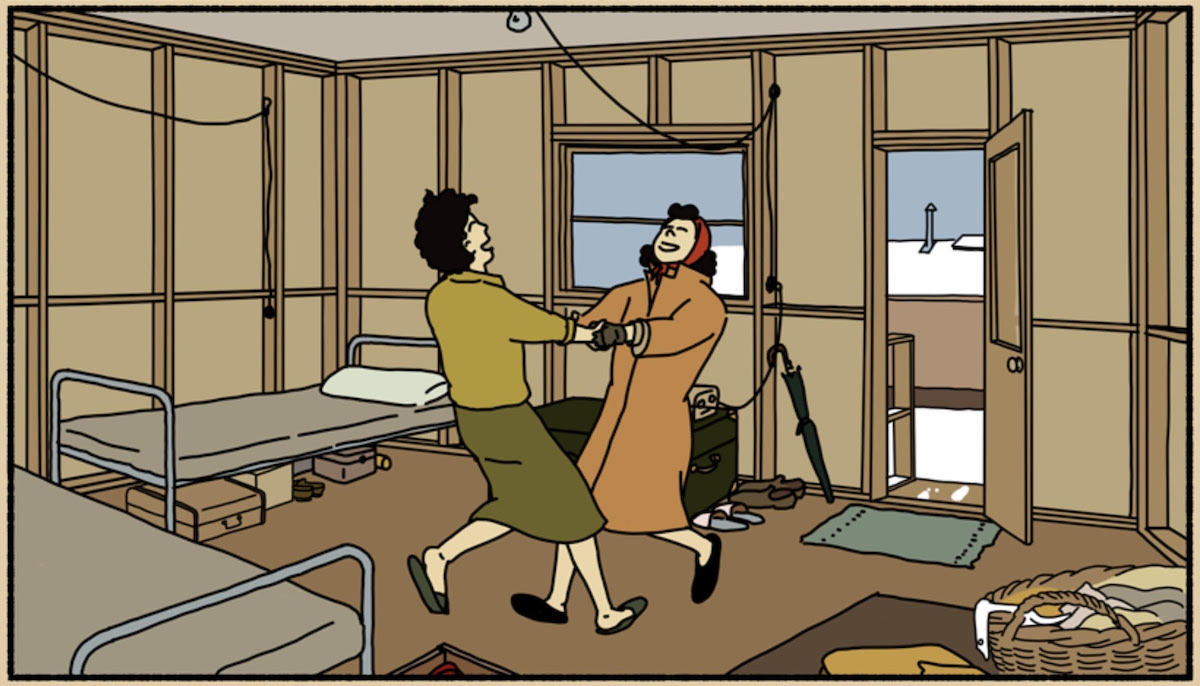

That same year, through a bibliographic reference at the Japanese American history site Densho, I found an academic journal article by Elissa Ouchida. Ouchida shared Endo’s story through the eyes of one of her best friends, Janet Sakaye (later Janet Masuda). Only then did I learn about Endo’s participation in a lawsuit with 63 other wrongfully fired Japanese American State of California employees. I was excited; this tied Endo to a collective organized action. I also learned that a bad experience with one news reporter made Endo reluctant to grant interviews. But perhaps most meaningful was reading that Endo and Sakaye “danced around the room” at Topaz when they received the news of Endo’s victory. Here was a rare place not just of Nisei women’s voices, but Nisei women’s celebration.

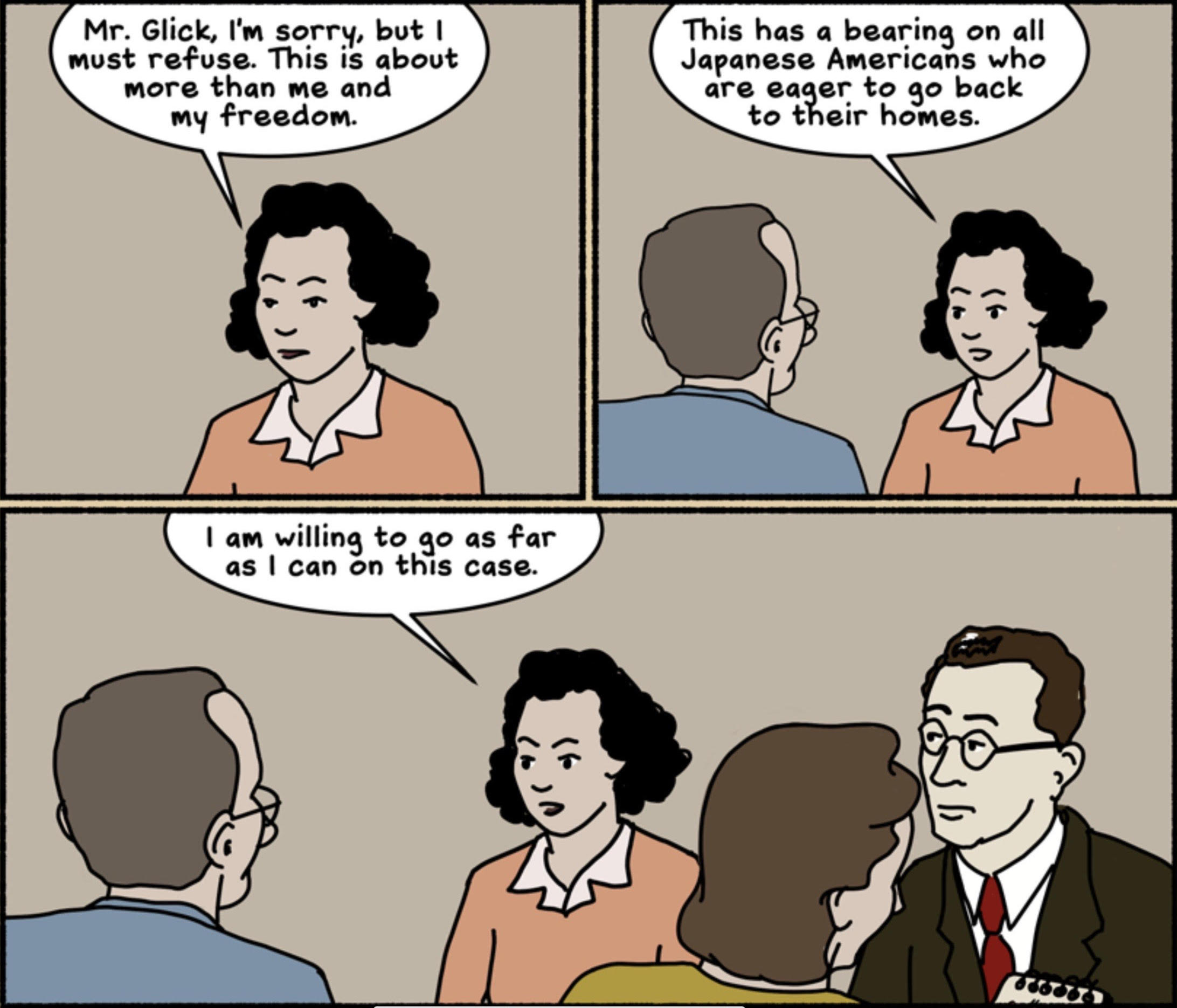

Excerpt from We Hereby Refuse. Artist: Ross Ishikawa, courtesy of Chin Music Press/Wing Luke Museum.

Shortly thereafter, I requested copies of a folder of correspondence between Endo and her attorney, James Purcell, from the California State archives. Scrolling through the 25 electronic pages, I felt vindicated: Endo’s voice emerged with the quiet strength I had only sensed in summaries of her case. One particular exchange from September-October 1943 stood out. In late September, Purcell warned Endo that the government was sending a top War Relocation Authority attorney, Philip Glick, to offer her a plea bargain. If she dropped her habeas corpus case, the government would release her from camp. She responded by writing that because her case pertained not only to the Japanese Americans in the class action lawsuit, but all Japanese Americans who wished to return to the West Coast, she was willing to take it “as far as she could.”

In that moment I recognized my own Nisei aunties, who made many quiet—but not silent—decisions for a collective good. I thought of my oldest auntie, who was released early from camp to work in a dentist’s household in Beverly Hills, and once sent back her entire paycheck to my grandparents and the rest of her five siblings.

When Endo refused, she was concerned about her personal safety; in the same letter to Purcell, she wondered about the possibility of anyone returning to California with her, given the hostile climate she had left in her home state. Though Endo could have joined her sister in Chicago (who had already been released), she did not, and remained behind barbed wire for months. That delay allowed her case to move forward until her unanimous victory in December 1944. She was not released until May 1945.

Excerpt from We Hereby Refuse. Artist: Ross Ishikawa, courtesy of Chin Music Press/Wing Luke Museum.

The world may know Endo best from that photo at the typewriter, but now I also think about her dancing with her best friend—or sending the telegram I discovered in her correspondence with Purcell. Dated December 19, 1944, at 2:47PM, just after she heard the news of their victory, it begins with the words “extremely joyous.” So many photos of Nisei women in camp have a restrained energy, thrown into stark relief by black-and-white photography. But this was unabashed joy I could feel echoing through the archives and decades.

Young people today might need images of leaders and resisters who were committed from the beginning, who questioned authority from the start. But I can also appreciate that Endo’s resistance was complex: that she was recruited to a cause, but stayed faithful to it at great personal cost. I wanted to show what resistance looks like when it is not a raised fist. I wanted a human path to a human decision, not a lionized figure on a pedestal. I wanted to show that resistance is not always male—and it is not always loud. In Endo’s case, resistance looks like a quiet, ironclad devotion to a collective good. In We Hereby Refuse, we quote Endo’s voice from her lesser-known 1976 interview: “I showed people what I could do.”

Send A Letter To the Editors