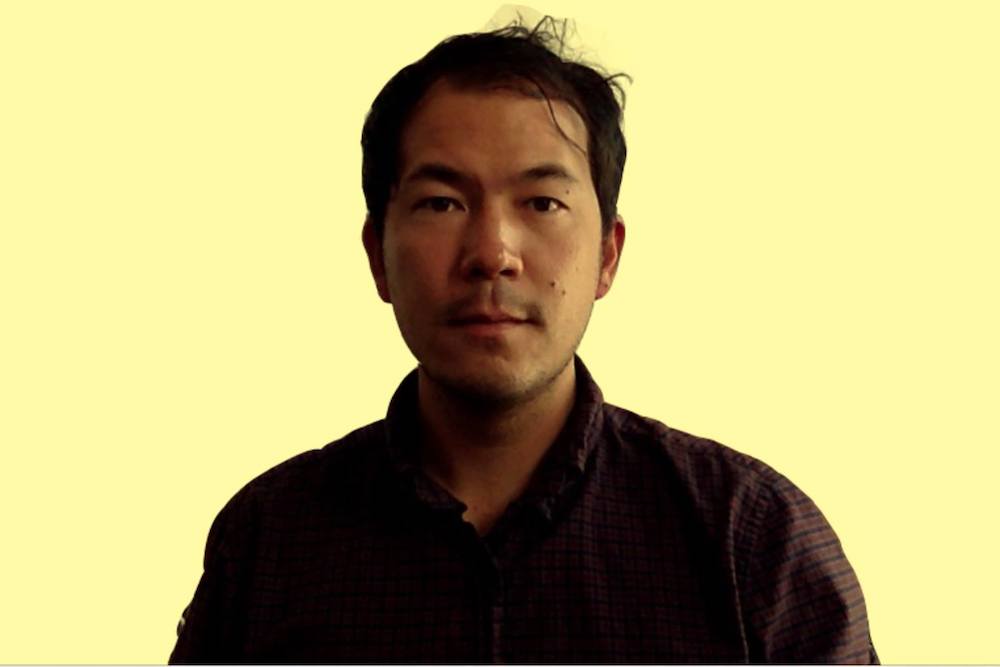

Rosten Woo is an artist, designer, writer, and educator who produces civic-scale artworks and collaborates and consults with a variety of grassroots and non-profit organizations. The co-founder and former executive director of the Center for Urban Pedagogy, and the author of Street Value, he teaches at the California Institute of the Arts, Pomona College, and Art Center College of Design. Before joining a Zócalo/L.A. Commons panel, “How Do Artists See the Next L.A.?,” Woo chatted in the our green room about speculative mapping in kindergarten, his advice for young designers, and getting paid to lawn bowl with a house painter.

When are you at your most creative?

When I’m walking around, doing something that’s really unfocused from trying to be creative.

Do you remember the first map that you made?

I think it might’ve been when I was in kindergarten. We’d make these maps that were essentially like giant war zones—you’d draw your little fleet of military equipment and your friend would draw one on the other side of the piece of paper, and then you’d draw lines across and cross out each other’s military installations. Those pencil wars were probably the earliest kind of speculative mapping that I did.

Have you engaged with any work during the pandemic that you feel successfully articulates this moment?

The social media factoid. It obviously existed prior to this last year of pandemic, but it’s a really standardized graphic format now: big text on a solid background explaining something horrible that has happened in the last week. That visual format feels like it’s really saturated my mind, and not necessarily in a good way, but it seems really present right now.

What’s your favorite piece of art that you own?

I have a Sister Corita Kent print that’s of an eye—like, a big owl’s eye—that I got when my first daughter was born. Her name is Ida, so it’s her name print. That’s a special work for me.

When have you experienced the most culture shock?

In L.A., you can experience culture shock very dramatically within a few blocks, when you’re just walking from Skid Row to Disney Hall or something like that. The worlds that are contained in and stacked on each other that have so little acknowledged relationship to each other is really jarring.

Your work is really collaborative and community based. Were you always good at group projects in school?

I learned to collaborate outside of school. I had a pretty developed creative life—even as a high school student growing up in the Pacific Northwest. I was really involved with punk and riot grrrl and the independent music community. It informed the way I think about what is valuable in collaborative making.

What smell evokes the strongest memory for you?

Rain. That has probably been seeded by having just described growing up in the Pacific Northwest.

How do you decompress?

I can’t tell if this is just me becoming like a really old man or being a tired parent, but I have to say for the last year, just lying down in a park—that, to me, is a peak experience. When I lie down in a park it’s like, “Ah, this is what it’s all about.” Just being able to lie totally still in some grass is amazing.

What question do you get asked most frequently by aspiring artists or designers or planners?

I often get asked, “How do I get your job?,” which is a funny question for me, because it didn’t really come to me as a job. When I started out doing this kind of work, the idea of being a socially engaged designer wasn’t a job. You couldn’t go to school for that; it wasn’t a thing in the way that it sort of is now.

So what’s your short answer for people who ask?

I say that the thing that ties my work and myself together is not a particular job, but a series of ethical commitments. That to me is the most important thing to figure out in shaping your career: who do you trust and who do you want to serve? And then figuring out how you can be of service to those things, whether that’s a particular community or a set of ideals. If you have those things in place, then you’re less likely to get pulled off course. And then you figure out the other pieces as you go.

What is the strangest job you’ve had?

When I was in college, I got a summer job working in the cavern underneath the National Archives building in Maryland. I had a stack of decaying political newspaper cartoons from World War One, and I was transferring them from newsprint and then photographing them with a large format camera. The thing that was odd about it was that it was my first experience with the scale of archives and the scale of bureaucracy. At that time, they were debating whether or not to digitize things.

One day, I went to the retirement party for this woman who had spent almost her entire career transferring a single set of records— audio recordings of the Nuremberg trials—from memo band onto quarter inch analog tape. The memo band was sort of like a cross between a record player and a cassette; it had a needle that went in grooves along a tape. It’s a poorly thought-out technology because the needles constantly skip and go on to the next groove in the tape, and it’s really complicated to reset. So her whole job was just to reset the needle when it skipped. But she didn’t speak German, so she had to listen and become attuned enough to this one particular process to figure out how to reset the needle.

There’s just hundreds of different stories like that—these really absurd Sisyphean tasks of archiving. So spending all day in this weird, totally underground bunker-like atmosphere with all these really depressed bureaucrats doing things like that was one of the weirdest work environments that I was ever in.

A much shorter story: I had a job as a house painter one summer, and I was working for this guy who really didn’t want to be a house painter, but he had a house painting business. And he would always want us to stop painting around 2—but I was getting paid hourly. So I’d always want to paint more, and he’d be like, let’s knock off, we’ll go hang out in the park or something. And I’d always be telling him no, I’m here to make money, I want to want more hours.

So by the end of this summer, he was paying me to hang out with him. He was really into lawn bowling, and he would pay me from 2 to 5 p.m. to lawn bowl with him. So that’s the weirdest job I had: lawn bowling with a 30-year-old house painter when I was like 17.