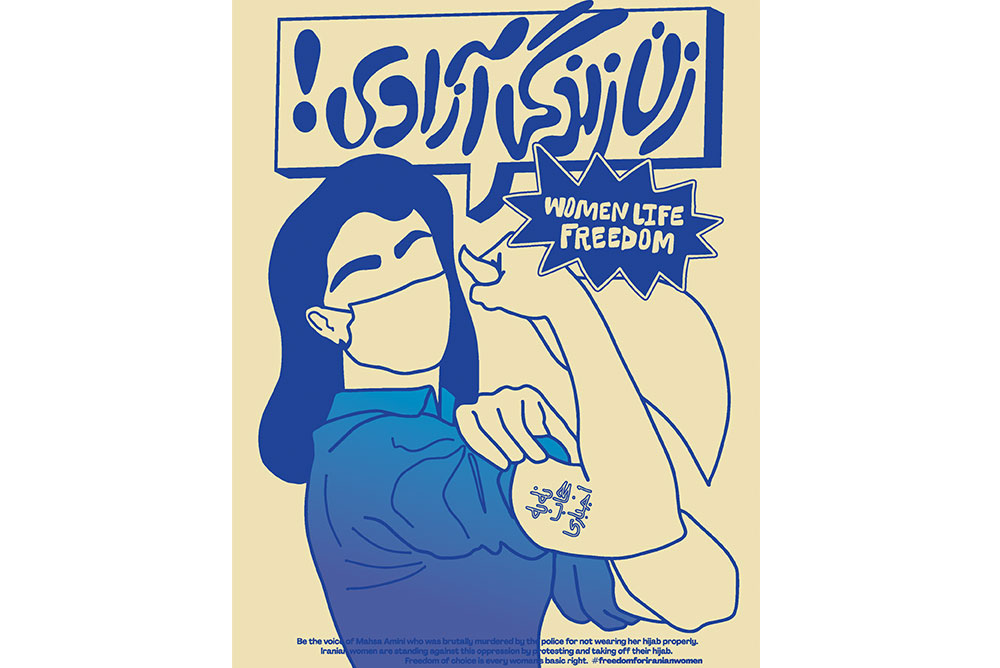

Iranian protestors have launched a movement to end discriminatory laws against women and imagine a new path forward, argues professor Catherine Z. Sameh. This Risograph print of a Rosie the Riveter-like Iranian woman reflects this transnational call for equality. Courtesy of Ghazal Foroutan.

The feminist uprising in Iran—sparked by the beating, arrest, and death in police custody of Mahsa (also known by Jîna) Amini, a young Kurdish Iranian woman accused of “improper hijab”—is generating previously unimagined ideas, images, and possibilities. The current movement, led by women and girls, has forced us all to rethink the glorified figure of the revolutionary as a militant, often militarized, and individual masculine subject. It also invites us to understand the complex history of women’s struggle in Iran—not as counterpoised to or lagging behind Western feminism, but rather on Iranian women’s own terms.

Indeed, this breathtaking moment builds on decades of feminist activism in Iran and underscores the significance of the women’s movement in the country in the decades following the revolution. The 1979 Iranian Revolution, sometimes referred to as the Islamic Revolution, was a broad-based movement against the corrupt dictatorship of the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, whose U.S.- and U.K.-backed rule had benefited a small and powerful elite and violently squashed dissent. The Shah implemented reforms in health, fertility, and education, but they helped primarily middle- and upper-class women. And so, the revolution captured the imagination and participation of many women, including those who were excluded from the Shah’s economic and social reforms—including rural, working-class, poor, and traditionally religious women.

The revolution also created a vast social welfare state with programs and services that dramatically increased literacy rates and life expectancy for women and men and increased the percentage of women in universities. Iranian birth rates also dropped drastically, by more than 70%—the average woman in the 1970s under the Shah gave birth seven times, a number that by 1985 had dropped to 5.6, and by 2000 had fallen to two. As the freedom of women’s and girls’ bodies is so central to this current uprising, it is critical to acknowledge that the post-revolutionary society invested in conditions that improved many women’s life chances, freeing them from poverty, illiteracy, inadequate healthcare, and lack of education. Nonetheless, these improvements were exacted at a very high cost for women: a discriminatory legal structure that legitimizes patriarchal control over and violence against women and girls.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, buoyed in part by their improved health and education, women mobilized to end the legal discrimination that was increasingly at odds with their growing social presence in Iranian society. Generally, an end to compulsory hijab has not been the central or most pressing issue around which feminists have organized. Rather, they’ve been compelled by issues like citizenship status, which until only recently was conferred through the father, rights in marriage and divorce, and custody of children, all of which seemed potentially winnable.

In 2006, following a demonstration in Haft-e Tir Square in Tehran, women activists launched the One Million Signatures Campaign, a local and transnational effort to end discriminatory laws against women, drawing on the unfulfilled promises of the revolution to grant women equality. The campaign sought to collect signatures from one million people in support of changing gender-based discrimination in Iran and demonstrating that these laws were not consistent with Islamic principles. The laws the campaign sought to challenge were mostly family laws pertaining to custody, marriage, inheritance, and divorce—in total 46 articles embedded in Iran’s Civil Code, 22 in the Penal Code, and one Constitutional article used to ban women from seeking the office of the president.

Activists went door to door to gather signatures, organized house meetings and public gatherings, and in general, built a movement based on collective participation and dialogue. In her book about the campaign, women’s rights activist and campaign co-founder Noushin Ahmadi Khorasani argued, “The power of the civil and democratic movement of the Iranian people must come not from blood, clenched fists, bulging veins, and zealous revenge-seeking, but rather from life-affirming endurance, persistence, and thoughtfulness.” Khorasani’s call for these last three traits challenges the ubiquitous figure of the charismatic and lone revolutionary male leader—for instance, Ayatollah Khomeini, who consolidated his power in and after the 1979 revolution and became, subsequently, Iran’s first Supreme Leader—offering instead a politics informed by feminist principles and organizational practices of collectivity, dialogue, and a deep embeddedness in the ordinary lives of people.

The campaign didn’t always succeed at being non-hierarchical—some campaigners received more attention and visibility than others, and class and ethnic divisions did emerge. Still, it was largely characterized by an emphasis on the importance and capacity of each participant, and an insistence on women’s rights as an integral component of Iran’s overall self-determination. Campaigners hoped to present the signatures to Parliament in the form of a bill, but ultimately they were unsuccessful at reaching the one million mark. Despite this shortcoming, the One Million Signatures Campaign and similar pragmatic efforts exerted sustained pressure on the state to address political demands for women’s rights. Moreover, they created organizational cultures based on deeply feminist visions of social change.

Khorasani and her fellow campaign activists also put forward an ethical, feminist, and everyday vision of Islam that stands in stark contrast to the state’s patriarchal interpretations of Islamic law. It is that vision that informs one of the many utterances of the present uprising: that compulsory hijab is un-Islamic, as is the state’s horrendous violence against women. As women in the current uprising defy compulsory hijab, they are not arguing against Islam, but against the conscription of their bodies into gender-differentiated regimes of power. They are making links to the bans on hijab in India and France, as well as to the bans on abortion in the United States. In this sense, they are challenging the binary between the “free” women of the West versus the “unfree” women of Iran, instead crafting transnational connections around the patriarchal and authoritarian attacks on women’s bodies.

This legacy of feminist activism is woven through the current uprising, which also might well be the unfolding of a distinctly new kind of feminist revolution. In the streets, schoolyards, universities, restaurants, shops, and homes of Iran, women and girls are demanding their freedom and autonomy and, in the process, creating relationships based on mutuality, solidarity, love, and care. Unlike their predecessors, however, they are not interested in negotiating within the parameters set by a patriarchal authoritarian state. In the multiple and extraordinary acts of celebration and defiance—removing and burning hijabs, dancing in the streets, eating in restaurants without hijabs, graffitiing walls, kissing in public, creating art, singing, cutting hair, taping sanitary napkins over surveillance cameras—women and girls are occupying space with their bodies and creating a new world of political symbols, ideas, practices, and visions.

This is their moment, no longer deferred to a future that never comes. Whatever the outcome of this exquisite movement, the women and girls at its heart are the new revolutionary figures on the world stage, showing us all a different path forward.

Send A Letter To the Editors