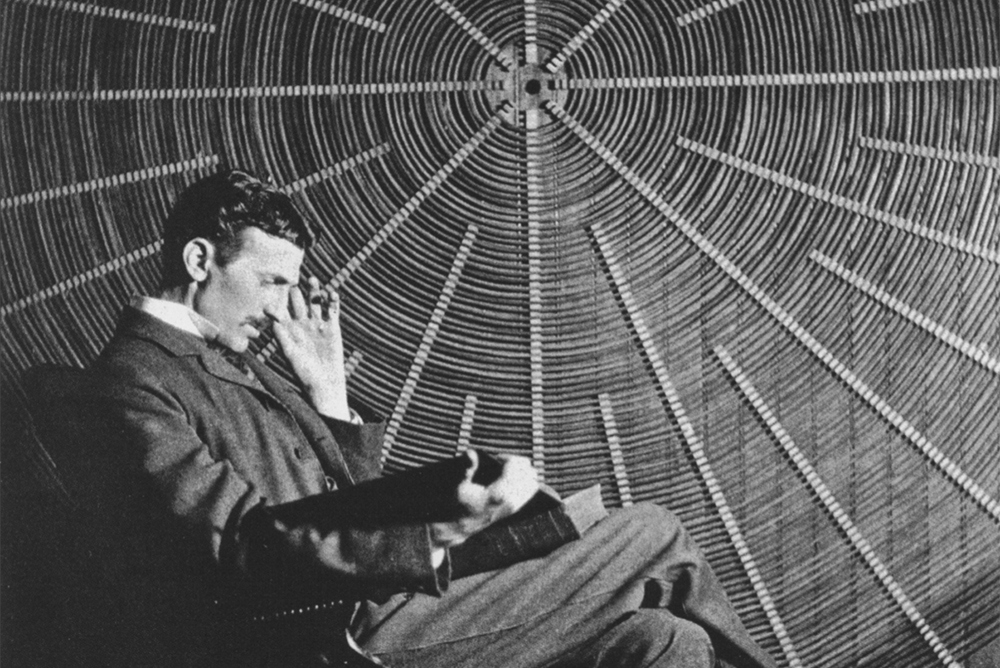

Victorian inventors, like Nikola Tesla (pictured above), are remembered as iconoclasts, who operated alone, outside the rules, to change humanity. But historian Iwan Rhys Morus explains why, in actuality, it’s not “lone genius mavericks” but collective efforts that shape our future. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Are tech bros the new Victorians? I’m sure they wouldn’t think so. In fact, I’m sure they’d be deeply insulted by the notion. The Victorians of our imagination are staid fuddy-duddies—and the captains of Silicon Valley are the cutting edge of the future.

But the Victorians, too, thought of themselves as masters of invention, just as tech bros do now. As we contemplate the role of new technology, and the men who dominate it, in everything from financial markets to climate change, the Victorians offer a cautionary tale and a glimpse of how we got to the place we’re in. By creating and perpetuating the myth that futures are built on the backs of heroic, self-made individuals, Victorians shaped today’s misbegotten sense that it’s lone genius mavericks—and not collaborative efforts—that shape our tomorrows.

Victorian innovators, like their contemporary counterparts, saw themselves surfing a wave of invention into a new technological century. Invention after invention transformed the Victorian world—steam locomotion, the electromagnetic telegraph, the telephone, wireless telegraphy, animated photographs, and of course, electricity: The list could go on.

So, who was responsible for this Victorian future? Who made it, and owned it?

In fact, progress was usually collaborative. The effort to lay a telegraph cable across the Atlantic, linking two continents in practically instantaneous communication, for example, required the collective labor of hundreds. But Victorian popular culture celebrated men of science and inventors as the future’s authors: Individuals who had the discipline, determination, and sheer grit needed to remake the world in their own image.

Samuel Smiles’ Self-Help, a popular inspirational book published in 1859, treated readers to glowing biographies of men like these, including Sir Richard Arkwright, inventor of the spinning frame, and steam entrepreneur James Watt. Smiles urged readers to regard the biographies of determined men as gospel—a truly shocking thing to say at the time.

“Watt was one of the most industrious of men,” wrote Smiles, “and the story of his life proves, what all experience confirms, that it is not the man of the greatest natural vigour and capacity who achieves the highest results, but he who employs his power with the greatest industry and the most carefully disciplined skill.” Inventors were special men, the thinking went (and it goes without saying that, just like tech bros, they were men).

The American icon of industrious, self-made inventor-entrepreneurship was Thomas Alva Edison, who famously said that successful invention was 10% inspiration, 90% perspiration and often played on his image as the self-made, all-American, plain-speaking and plain-working man of action. No fancy theory for him. The future was going to be the property of the plain man made good. When, in 1898, pulp fiction author Garrett P. Serviss wrote a quasi-sequel to H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, it was a fictionalized Edison, captain of industry, who led the avenging fleet of electrically powered spaceships to Mars.

The flamboyant inventor and self-promoter Nikola Tesla—who competed with Edison and carefully cultivated his own image as a reclusive iconoclast and rule-breaker—provided a different, but related, model for Victorian invention. Tomorrow belonged to people like him (well, actually, only him, in Tesla’s opinion). “Nikola Tesla says Men of the Future may become as Gods,” screamed a New York Herald headline in 1900. The “great magician of electricity” pronounced that “war would be abolished,” thanks to his inventions, and that he would “work a revolution of the politics of the whole world.”

Tesla worked hard to hone his outsider-hero image, and kept on working at it until his death in 1943. A series of biographies polishing his reputation began rolling out soon after, with John Joseph O’Neill’s Prodigal Genius of 1944, and in recent years he’s been namechecked by everything from Doctor Who and The Big Bang Theory to the Disney cartoon Gravity Falls. That image of the inventor as iconoclast, operating outside the rules, is clearly a very seductive one.

There’s little question which of the conflicting Victorian images of invention Silicon Valley’s tech bros prefer; that car wasn’t called Tesla by accident. But channeling the iconoclast makes aspiring tech entrepreneurs very Victorian indeed. Despite the hype, Tesla really was a man of his own time.

His is the Victorian vision that works for now. You succeed through provoking difference, not by excelling at what’s here already. It’s the cult of individual iconoclasm taken to its extreme. Tesla promised that men might become as gods, but only if they bought into his vision of the future. It’s that seductive vision that makes the values of disruption seem so attractive now, too. Disruption seems to offer a road to power—and that’s apparently true for many politicians, as well as tech entrepreneurs.

But in reality, disruption was a Victorian fantasy, rather than actuality. Tesla died penniless, his innovations abandoned for other technologies, and it had nothing to do with the excuses he promoted. Edison didn’t steal his ideas, and unscrupulous capitalists weren’t terrified by his inventions. Tesla died penniless because he made the mistake of believing his own publicity. He really did think he could single-handedly forge the future through disruption. But his example suggests the opposite.

In the end, the Victorians show us that futures are best made collectively—when we build them to address what communities genuinely need now, instead of offering castles in the sky.

Send A Letter To the Editors