Artist and art consultant Jen Hitchings explains the tricky business of balancing financial calculations with personal, cultural, and creative values. She considers, for instance, the price of Urs Fischer’s “You,” (featured above) an excavation of the foundation of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise gallery in New York. Courtesy of Barry Hoggard/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

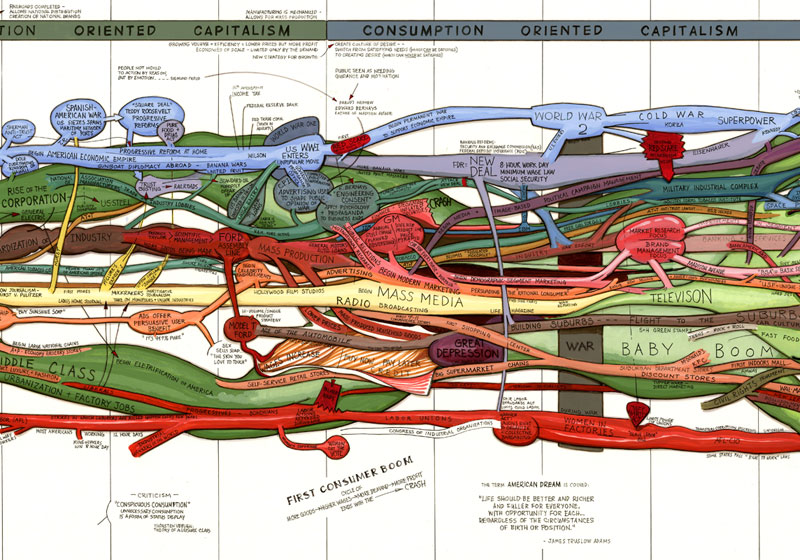

All artists exist within a larger ecosystem of creativity. Artist Ward Shelley’s timeline-inspired paintings and prints of interrelated people, places, facts, and events visualize this ever-evolving cultural milieu on mylar. His subjects range from politics and the evolution of science fiction to downtown New York’s counter- and sub-cultures. These works are both complex and beautiful, but they are also unique in part because his gallery prices them based on the arduous, sometimes years-long research required to develop them. This pricing calculation is antithetical to most galleries and artists; typically, until an artist’s own market is truly established, the amount their work sells for is determined by its size.

Like the works themselves, Shelley is more interested in the ecosystem of the arts than in profit. He often makes multiple versions of a painting—and produces and sells editioned prints—as he continues to discover new connections and histories about his subjects. “Sharing information is the most important aspect of making art to me—at times I send hi-res image files of works to those who ask,” Shelley has explained. “I rely on the trust and honesty of friends and peers who ask for files, hoping they won’t turn around and sell the file to a company that will mass produce and sell prints without my knowledge … but I’m willing to take that risk, since I’m more concerned with sharing than selling the information and images I create.”

As an artist, art consultant, and director of the Patty Disney Center for Life and Work at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), my life and work revolve around not just art and its creation but also the economic sustainability of being a contemporary artist. For my colleagues and me, who essentially function as a career services office, that means acknowledging that artists of all disciplines—from music and film to fine and performing arts—enter the art world as entrepreneurs, working as their own managers. Each individual artist must design their own strategy to chart a path to their own definition of success. Some endlessly search for the nonexistent guidebook, while others use the journeys of artists before them as a guide. Most approach lifelong creative careers with endless curiosity and innovation, making it up as they go.

It can be tricky for emerging artists to ascribe monetary value to their work—and to balance the importance of its financial worth with a multitude of other personal, cultural, and creative values. There have been plenty of articles published on the production cost of Urs Fischer’s “You,” a 38-by-30-by-8-foot excavation of the foundation of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise gallery in New York in 2007—$250,000. What is its value, and how does one price (and sell) a hole in the ground? I can’t find the retail price, which isn’t surprising—partly because of the piece’s nature and partly because that’s how the art world works. Until a piece enters the secondary market, and especially if it’s being sold by one of the top 10 galleries, regular people probably won’t be able to find out what it costs. This is one of the reasons the largely unregulated art world appears to be elitist and opaque. That is changing slowly, and in part due to new technology: The online brokerage and search engine Artsy and other platforms make works and prices public and accessible to everyone, even though galleries can still choose not to list artwork prices on the platform.

“Work, Spend, Forget (Dissected Frog Polemic)” by Ward Shelley (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Pierogi Gallery, New York.

Art tends to make headlines beyond art publications only when the market determines astronomical and seemingly absurd monetary values. But in our line of work, we always keep in mind that the artists we’re training create work that has different kinds of value: in activism, decolonization, politics, privilege, gender disparities, identity, and so many other aspects of economics, sociology, and consciousness. And sometimes they bring value to the art world itself. David Hammons joined New York City street vendors to create his 1983 Bliz-aard Ball Sale, selling snowballs of various sizes to passersby. The work comments on the absurdity of the art market, questioning class, race, and capitalism. Today, art schools around the country teach Hammons and his work, which continues to push boundaries and make waves, as examples of both conceptual brilliance and biting societal critique.

Even as arts educators spend a great deal of time exploring how art reflects and refracts the issues of our time, many institutions still consider it unnecessary to educate students about how to actually make a living as an artist. They neglect practical skills such as marketing, budgeting, and communications. Yet artists all over—who have immediate, nearly free access to a global audience—need these skills, which allow them to take control of their sales and networking strategies. That, in turn, increases their visibility and the chance of securing a show, grant, fellowship, or residency anywhere in the world.

This is the arts ecosystem into which I am trying to prepare students to enter—one of opportunity, access, innovation, and excitement. My job is in part to help them feel prepared and confident to use the tools available to challenge the status quo and move the cultural needle forward.

Many of the students are teaching me in the process. In fall 2022, recent CalArts MFA graduate Eliot Burk, a composer, presented his final recital, Seven Strategies for Ending Music. The performance had several parts in several locations, and included volunteers destroying nearly 300 instruments, already in various states of disrepair. I was among the audience members watching as they dropped or hurled saxophones, guitars, clarinets, cellos, and other instruments over the campus balcony outside of CalArts’ Herb Alpert School of Music, to crash against the concrete slab below.

The piece critiqued the field of music as a whole and the human-object relationship that creates sound. I was strongly moved by the entire performance and happening; to me it was a beautiful sensory, meditative experience. But the loudest initial audience response emerged from assumptions surrounding the value of the instruments—the objects—rather than the intention of the project as a whole. But what if, rather than thinking of art and the people and objects that make it in terms of monetary value, we looked at this performance as just one part of a Ward Shelley ecosystem? An art world where we don’t deny that things—supplies, time, and higher education—cost money, but where we also recognize the value of creativity is fluid, subjective, and does not always translate to currency? That is an art world I want to help cultivate, and participate in.

Send A Letter To the Editors