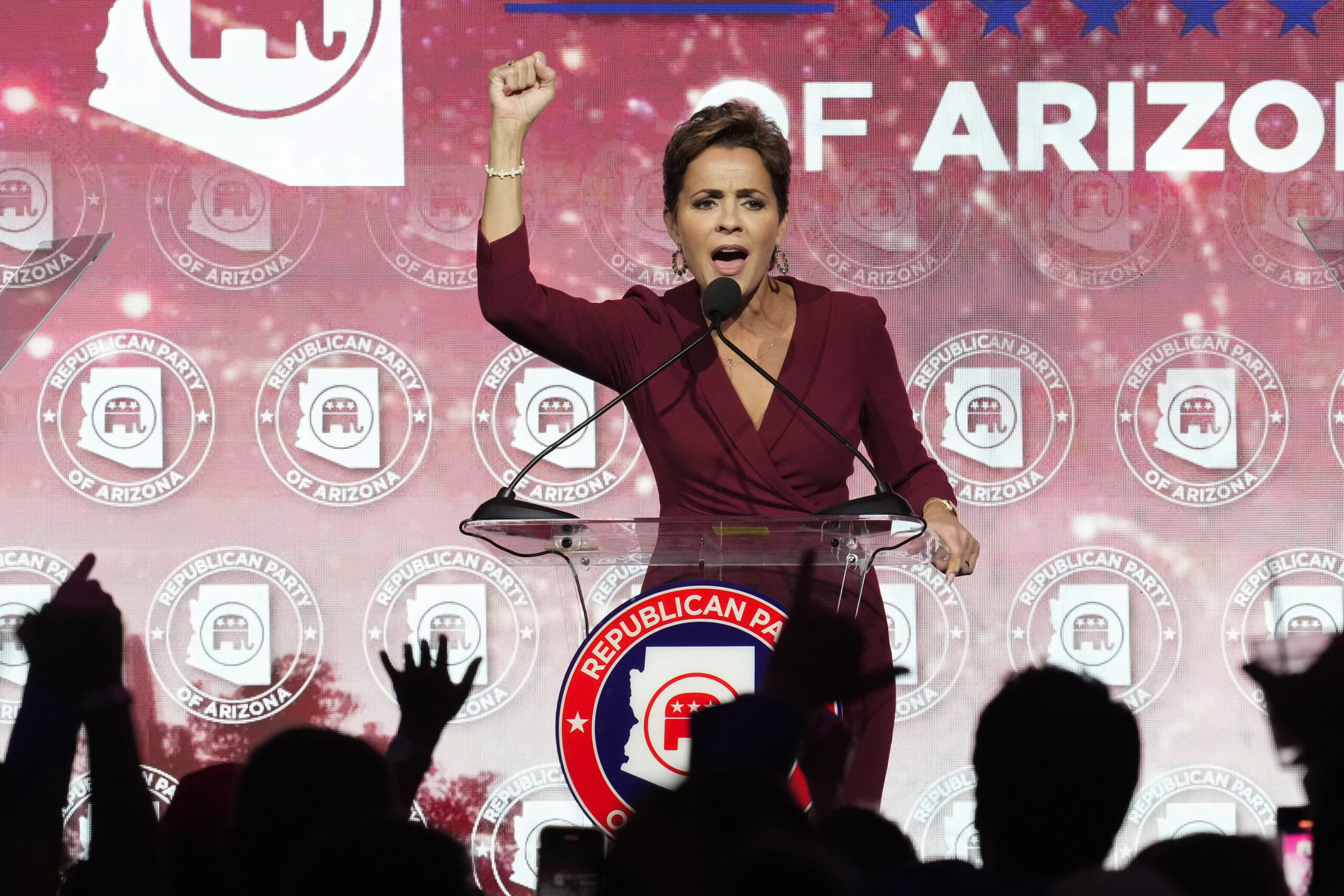

Kari Lake may be an Iowa native, but the politician’s embrace of Arizona’s “pie-in-the-sky identity” situates her within the state’s long tradition of desert hustlers, writes Rim to River author Tom Zoellner. Courtesy of AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin.

Kari Lake isn’t giving up. Even as she prepares to mount a campaign for U.S. senator, and more than two months after her election opponent was sworn in as Arizona’s governor, she swears that it is she who is the real governor of the state. She continues to insist the election was stolen.

Election denial has become one of the pillars of the modern GOP—but the desert soil of Arizona soaks up such hallucinatory claims like rain, at least partly because of the state’s unique history. Through most of the last century and a half, Arizona has been a geography of personal reinvention, ambitious schemes, and glowing hype that exceeded nature’s limits. The name itself is derived from a 1736 silver rush in a valley near a ranch called Arizona that flamed out just weeks after it began. Lake’s false crusade has already lasted longer.

What’s in the water in Arizona that inspires such obvious flimflammery?

Well, for starters, what water? A make-believe approach toward hydrology has characterized Arizona’s modern development. A state with an average annual rainfall of just 12 inches grows tens of thousands of acres of high-moisture cotton and supports more than 370 golf courses, in addition to 2.7 million households. Its allotment from the Colorado River was based on wildly optimistic flow projections, a century ago; by the 1960s, the state had to build a 330-mile canal to push H2O uphill, away from its great rival, California. A lengthy drought and falling levels in Lake Powell, the country’s second-biggest reservoir, are now throwing future real estate ventures and population growth into doubt.

Fecklessness with limited water is practically written into Arizona’s DNA. In 1912, federal money put what was then the world’s biggest dam on the Salt River, and the farmer-aristocrats in the new state legislature thought so much of it they put its image on the official state seal. But their exuberance over the new Eden in the Desert—they thought the land hid mammoth springs beneath its surface—was overblown. “Underground waters were believed to be virtually inexhaustible,” said a 1949 Bureau of Reclamation report, published after most of Arizona’s surface water had been exhausted. “People held firm to the concept of vast underground rivers pouring endlessly to the sea and proceeded to develop more land.”

Land didn’t even need to be improved much to be a hot commodity in the state’s thunderdome of wishful thinking. During the 1960s, shady real estate brokers treated Arizona like a dry Florida with cactus, with homesites of worthless scrub sold to buyers through the mail via glitzy magazine advertisements, sight unseen. Dupes were horrified when they showed up in person to see barren lots, in the middle of nowhere, without utilities.

Big land hustles like Golden Valley, Prescott Valley, and Rio Rico—stretches of wasteland that a previous generation of cowpunchers had valued at just pennies on the acre—gave the state a dirty reputation nationwide. But gullible buyers always played a key role in settling Arizona, and these were only the latest incarnations of swindles of prior eras. The most famous early scoundrel, James Reavis, “The Baron of Arizona,” managed in the 1880s to convince hundreds of landowners between Phoenix and Silver City, New Mexico, to pay him quitclaim fees. He told them he was heir to a massive 18th-century grant from Charles III of Spain. Never mind that the grant was written on paper bearing the watermark of a Wisconsin mill. Reavis made a fortune.

Promoters touted dozens of flea-bitten mining settlements as the next Chicago or Pittsburgh in the frosted words of late-19th-century town boosters. John Clum, the founding editor of the state’s oldest continuously published newspaper, the Tombstone Epitaph, published the first issues of his paper from under a canvas tent. But that didn’t stop him from proclaiming the gang-infested silver town “a city set upon a hill, promising to vie with ancient Rome, in a fame different in character but no less in importance.”

Perhaps the paradigmatic novel of this state of highflying dreams and bitter realities is The Circus of Dr. Lao, published in 1935 by an Arizona Daily Star copyeditor named Charles G. Finney. The title character is a huckster who rolls into the fictional Arizona town of Abalone with cages full of mythical creatures like satyrs and sea serpents. Some townspeople think the beasts are ordinary livestock dressed up in ridiculous costumes. But are they?

Arizonans see what they choose to see. Before he went to federal prison in 1992, savings and loan king Charles Keating built a gilded luxury resort here called The Phoenician, off the filched earnings of thousands of widows. During the 1964 presidential race, revered U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona suggested he would defoliate the tree cover over the Ho Chi Minh Trail with nuclear weapons—and for good measure, he would “lob one into the men’s room at the Kremlin,” too. It cost him the nationwide nomination, but people back home loved it.

A lack of rootedness doesn’t help. Nearly 60 percent of today’s Arizona residents weren’t born here. The real estate economy functions like a Ponzi scheme in that sense, requiring a constant stream of buyers from elsewhere to justify the endless expansion of stucco roofs to the desert horizons. This is still the fastest-growing state in the West, with a 1.3% population uptick since 2021.

Part of the Arizona Dream is that you can move here with no family connections and no history and fit right in—even get elected to high office. People migrate here for a second chance and a fresh start in the land of wide-open skies and new opportunities. Without question, those exist, as do the knowledge, pragmatism, natural beauty, and neighborly character that give Arizona enduring appeal. But charlatans still hide in the sunshine. Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics surveyed reporters in 2014; they named Arizona the most corrupt state in the country.

Kari Lake—a native of Iowa who moved here for a job as a TV anchor—demonstrates a grasp of an enduring aspect of the state’s pie-in-the-sky identity with all her proclamations of buried treasure lying somewhere in those ballots. There are those who see hope in the state’s recent leftward tilt, via electing a Democratic governor, throwing its electoral votes to Joe Biden, and shifting the political gravity away from cosplay clowns like Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who thought he could clean up Phoenix by dressing jail inmates in pink underwear and making them live in canvas tents in the desert. But Sen. Kyrsten Sinema changed her registration from Democratic to independent, setting up a potentially chaotic three-way Senate race in 2024, and the legislature remains in the hands of those who yelled “election fraud” loud enough to conduct an expensive recount that took months and showed nothing. They remain unrepentant, and their donors keep writing checks. Perhaps those who wish for a straightforward fade from red to blue are also chasing rainbows.

Send A Letter To the Editors