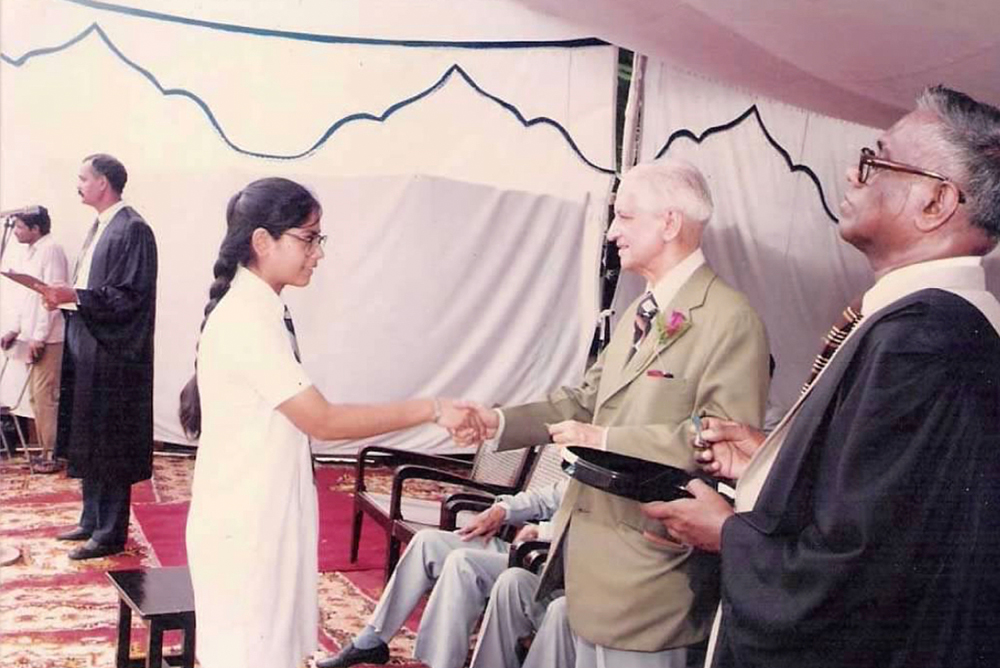

Zócalo executive director Moira Shourie offers a glimpse into her community, the Anglo-Indians (AIs), and recounts her family history. Pictured above is young Moira receiving an award from AI leader Frank Anthony in 1990, as her father looks on. Courtesy of author.

“I thought they died out,” a woman remarked flippantly to my friend just the other day. She, like many Indians, has long believed that Anglo-Indians ceased to exist when the British left the subcontinent. But despite a recent Indian government effort to strip us of our legislative protections after a bogus census count, we have endured.

I am Anglo-Indian—AI, as we are commonly known. I am not dead. In fact, there are over 350,000 of us in India today. And our history tells the story of a group of people that straddle two worlds, offering a glimpse into the complexity of colonial and postcolonial life. It is also the story of how a small minority group has nurtured a deep sense of community for hundreds of years in Indian society, which has both embraced us and held us out as vestiges of a foreign occupation.

Yet we have remained invisible in most colonial histories. Article 366(2) of the 1950 India constitution defined an AI as “a person whose father, or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line, is or was of European descent, but who is domiciled within the territory of India and is, or was, born within such territory of parents habitually resident therein, and not established there for temporary purposes only.” My childhood friend Barry O’Brien, in his exhaustive book The Anglo-Indians: A Portrait Of A Community, traces the story of AIs, “one of the oldest and largest communities of mixed descent people in the world,” back to 1498 “when Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese explorer, set foot on the shores of Calicut—a whole century before the British arrived in India.”

All my grandparents—Wilfred Mayer, Mary Michael, Benjamin D’Monte, and Vida Chatelier—were born in British-ruled India, as were their parents and most of their grandparents. My parents, George Mayer and Alicia D’Monte, were born before India won independence in 1947.

My family spread out across the subcontinent following the veins of the growing railway network. My grandfather Benjamin D’Monte was an engine driver who succumbed to lung cancer after a brief life spent shoveling coal into the belching boilers of English engines. His daughters, my mother, and her sister, Lourdes, grew up in a railway colony in the southern Indian town of Podanur.

Over centuries, Anglo-Indians have formed composite identities in the multiracial population of India. Like our forebearers, AIs are Christian and multilingual: our mother tongue is English, and we often speak Hindi and the languages and dialects of the places we originated from (like Konkani, Bengali, Marathi, Kannada, Tamil, and Telugu). For generations, we married mostly within our community. We exist outside the Hindu caste system, and have been referred to in derogatory terms like half-caste, kuccha bachha (half-baked child), and no one’s favorite, “bastards of the British.”

We have endured slurs and been alienated by our own people. We have been made the punching bag of every nationalist politician. The Indian stereotypes of Christians in general and AIs in particular are promiscuous, drunk, lazy louches. Hindi movies reinforce this idea by naming cocktail waitresses—symbols of loose morals—Mary. It was particularly harrowing for my parents to raise three daughters in a society that saw girls wearing skirts as fair game for sexual harassment.

This alienation had at least one positive effect: AI women gravitated toward careers that went against the restrictive gender norms of Indian society, working in public-facing jobs as teachers, nurses, secretaries, and flight attendants. As people with professional training and college degrees and a mastery of speaking English, many AI families rose into the middle class within a generation of India’s independence.

Our in-between status also created cohesion. In 1926, Sir Henry Gidney formed the All India Anglo-Indian Association to create a central financial, political, and cultural hub for our community. Among its early leaders was Frank Anthony, a London-educated lawyer, who in 1942 negotiated with Gandhi, Nehru, and leaders of the independence movement to enshrine legally-protected representation for Anglo-Indians in the infant country. Still, at that time, many AIs left India along with the British and emigrated to other Commonwealth countries like Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

But AIs have found ways to keep our subculture alive through music, food, and the annual general meeting. AGMs are usually held during the Dussehra-Diwali holiday season in October and cover a wide range of issues, from education and sports to civic participation. While our parents engaged delegates from all across the country in debates about the future of our community in the great hall of Frank Anthony Public School in Delhi, we kids played childhood games that morphed into teenage dance parties that blossomed into romantic relationships. Every year new couples found love, new romances were celebrated, new babies were christened. Moira Georgina Mayer was one such baby, crowned “Most Beautiful” in 1973, and paraded by Mr. Anthony’s wife, Olive, or “Beaut,” as she was affectionately known. And so we Anglo-Indians ensured our longevity and our sense of identity, even as a mere 0.01% of the Indian population.

I remember Christmas dances filled with the music of our very own Cliff Richard (born Harry Rodger Webb in Lucknow in 1940) and Engelbert Humperdinck (born Arnold Dorsey in Madras in 1936). Where ladies copied fashions and hairstyles sported by Hollywood stars like Merle Oberon (born Estelle Thompson in Bombay in 1911). And the menu consisted of dishes like glassy, pepper water, jalfrezi, country captain, and yellow rice with ball curry, a bed of turmeric-tinged coconut rice with a spicy tomato-based meatball curry. After all the uncles and aunties turned in for the night, we teenagers would bring out guitars and makeshift drum sets for spontaneous jam sessions, dancing along to ABBA, Lobo, Boney M., and Shakin’ Stevens. Often, a power outage would send us out to the school’s cricket field, where our neighbors from the surrounding Lajpat Nagar colony would pour out onto their balconies for respite from the oppressive heat and to enjoy the spectacle of Anglo-Indian youngsters partaking in wild revelry. On those nights the unofficial AI anthem was “Roll Out the Barrel,” a song that perfectly captures our lightheartedness, and love for a dance and a stiff drink to wash off the day.

I moved away from India to the U.S. when I was 24. Because I didn’t marry an Anglo-Indian man, my children are not AIs. But I continue to share the rich and hybrid culture we made our own with them. And so, the essence of so much of my community survives. I feel that they sense it in the way I speak, in the AI lingo I use when speaking with my sisters that sends my sons into conniptions (“Come on men Moira-girl, chuck off in the mouth,” which is AI-speak for “have a bite to eat, Moira”). And in the subtlest of my mannerisms. And not least in the food that nourishes us, often drawn from the handwritten cookbook my own mother gave me as a parting gift before I boarded my flight to Boston for graduate school, filled with recipes for Nana’s roast, bloody cutlets, mixed grill, and that signature dish of Anglo-Indians everywhere: yellow rice and ball curry.

The Anglo Indians Favourites Playlist:

Send A Letter To the Editors