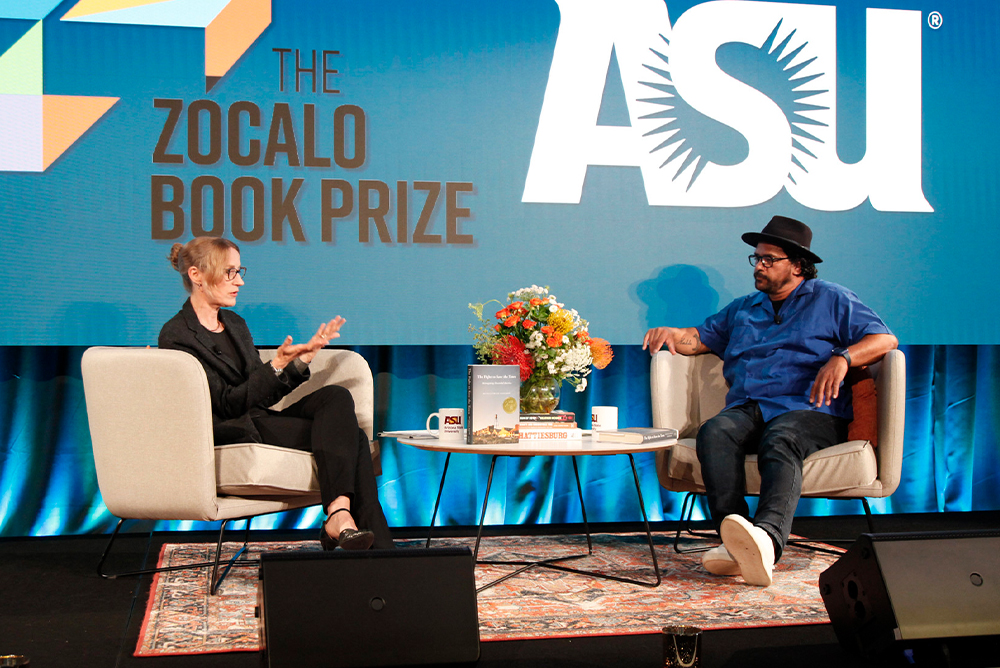

Michelle Wilde Anderson (left) and Alberto Retana (right).

Four of the poorest, most maligned places in America have become beacons of hope—and burgeoning centers of trust, in people and local government—since going broke in the Great Recession. How did they pull themselves up from an especially low point, and what can the rest of the country learn from them?

This was the subject of 2023 Zócalo Book Prize winner Michelle Wilde Anderson’s The Fight to Save the Town: Reimagining Discarded America, which we honored last night as the year’s best nonfiction book exploring community and social connection at the Zócalo Book and Poetry Prize event.

Held at the ASU California Center in downtown Los Angeles, the program, which also streamed live online, began with a virtual reading by this year’s Zócalo Poetry Prize winner, Paige Buffington, of “From 20 Miles Outside of Gallup, Holbrook, Winslow, Farmington, or Albuquerque.” Then, philanthropist Tim Disney—the sponsor of the program and both prizes—took the stage, where he lauded The Fight to Save the Town as “a moving and important document, and a timely one.”

Anderson received $10,000 in prize money and a pre-solved Rubik’s Cube, emblazoned with the Zócalo logo, for winning this year’s book prize. She announced she would be keeping the Rubik’s Cube, but donating all of her winnings to four organizations she wrote about in her book, and to South L.A.’s Community Coalition. “Because if this book moved anybody, that is because, above all, these people moved me,” she said.

During the 13th annual Zócalo Book Prize lecture, Anderson shared stories from the four places she wrote about: Stockton, California, Josephine County, Oregon, Detroit, Michigan, and Lawrence, Massachusetts. Since the 1980s, these towns and cities and others like them—often older, industrial cities with decaying housing and infrastructure, and high levels of environmental contamination—have grown poorer because of disinvestment from state and federal government and poorer tax bases.

“These cities are broke in part because they’re poor, and their people stay poor in part because their governments are broke,” said Anderson. “This is actually the start of a larger, vicious cycle of decline in which the conditions of poverty undermine the basic trust that is needed for human cooperation.”

But in each place, she found examples of how people and institutions are facing this vicious cycle and finding ways to work together to break out of it. In Stockton, that meant addressing the trauma and mental health effects of violence, segregation, and intergenerational poverty. In Josephine County—one of the most anti-government places in America—that meant saving public services by convincing angry, skeptical voters that it’s possible to build cooperation and trust in government. In Detroit, that meant fighting foreclosures and speculators, and putting property back into local hands. And in Lawrence, that meant forming strong, pan-Latino networks to help residents in the 21st-century economy make a living wage.

“All of these efforts add up to social repair,” said Anderson.

Following the lecture, Alberto Retana, president and CEO of South L.A.’s Community Coalition—which, like many of the organizations in Anderson’s book, engages in ground-up, locally focused work—joined her on stage to talk about The Fight to Save the Town’s inspirations, and how to apply some of its lessons to other communities around the country.

Retana noted that Anderson’s book celebrates what democracy is all about: “people fighting to make something beautiful from something broken.” How, he asked Anderson, did she come to this subject and perspective?

She said she chose to write a “people-centered” book because she’s “really concerned that the way we tell stories about poverty is part of the problem.” Our narratives of poor places feature “crooks in the government and bullets flying everywhere and hell holes … Those narratives reinforce faithlessness that things can be better. So they give outsiders an excuse to stop working alongside people on the ground.”

You can see this dynamic in Los Angeles, a city of 40,000 unhoused people, particularly among the white middle class, Retana agreed. But what, he asked Anderson, is the “heart of the heart of the central solution” to tackling poverty and disinvestment?

“Turning government back toward its people,” said Anderson. “We have to invest in people where they live.” But she cautioned that one community cannot write the playbook for other communities. To the extent that, say, Lawrence has a method to teach the rest of America, it would be “showing up and listening,” and forming tight and supportive networks among people and organizations.

Why center the book on these local networks? Federal and state policy cause many of the problems they are tackling, said Retana.

It’s true that the problems are systemic, and we need federal and state policy changes, said Anderson. But upper tiers of government don’t work without this grassroots level—which creates places for outside funding, policies, and philanthropy to land.

Anderson turned the question back on Retana—whose work is local, after all.

The greatest changes in American history, he said, come from localities up—“whether it’s Ferguson in 2013 or Birmingham, Alabama, in the ’60s, or Los Angeles solving the homelessness crisis in the next few years.” He added, “I really love this book because it recenters the conversation where it really needs to happen: in our backyards, on our blocks, in our living rooms.”

After concluding their discussion, Anderson and Retana turned to audience questions, which largely centered around their advice for people and organizations hoping to effect change locally.

In response to one person who wondered what opportunities community-based organizations might be overlooking, Anderson shared a lesson from Stockton. There, a youth development program gathered all the local youth programs staff together one morning a week for orange juice and doughnuts. “It was an incredible moment for the city’s network-building,” she said—not because spectacularly important plans got made in these meetings, but because they helped people and programs get to know one another and coordinate in an environment of scarcity. “I do think there’s a form of casual coordination that we don’t give enough credit to as a component of social change,” she said.

Last night also kicked off Zócalo’s 20th birthday celebration, and before the program wrapped, Zócalo executive director Moira Shourie took the stage to thank Zócalo’s past and present staff, funders, and audiences for their support over the past two decades, through more than 700 public programs and 3,000 published essays. And then, in true Zócalo fashion, everyone came together for cake and more conversation.

Send A Letter To the Editors