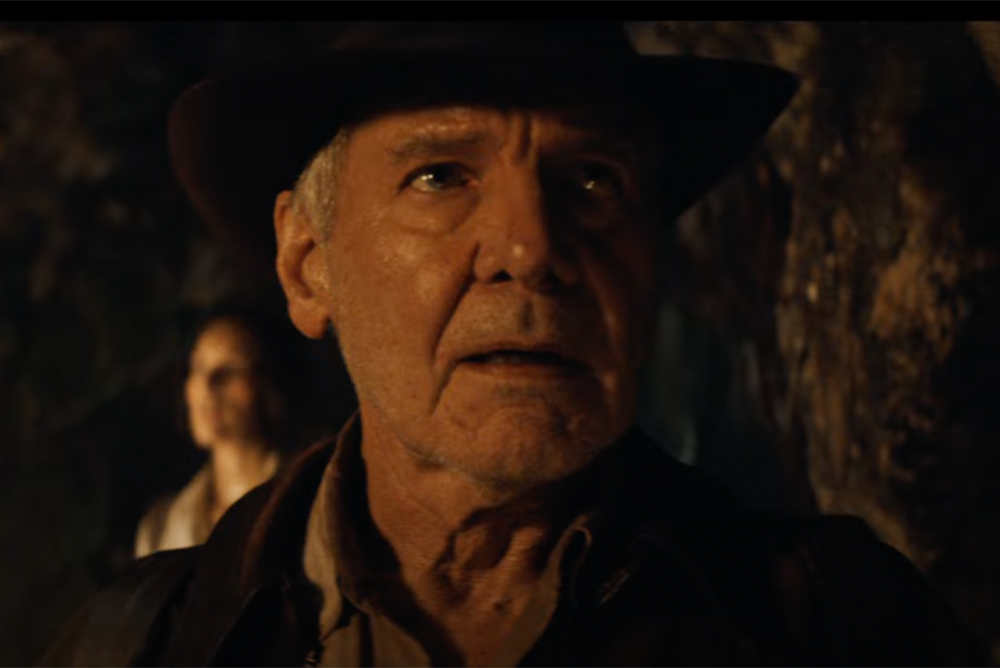

Indiana Jones may be taking a final bow in “Dial of Destiny,” but the shadow he’s cast over archaeology remains, writes Culture Class columnist Jackie Mansky. Courtesy of Lucasfilm/Disney.

In 2009, soon after the fourth Indiana Jones film came out, the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) awarded Harrison Ford with the Bandelier Award for Public Service in Archaeology.

In his speech, Ford expresses his gratitude to the AIA and for the work archaeologists are doing today to “understand and interpret the past to learn from it and enjoy a better future.” But he added, “it is quite disarming to see that the Indiana Jones films have been an inspiration to archaeologists.”

I was thinking about this speech while watching the previews for the latest Indiana Jones film, where Ford takes his last bow as Dr. Jones, the archaeology professor-cum-international treasure hunter. Three decades since 1930s-era Nazis sought to take over the world in Radars of the Lost Ark, they’re back in this fifth installment, The Dial of Destiny, set in the late 1960s, which finds them once more in pursuit of a powerful artifact (this time, a time-traveling device they can use to change the past).

Who better than Indy to save the world again? But if our now-aging hero is deservedly beloved for his penchant for punching Nazis (and his “healthy respect” for snakes), his own exploits also further what Ford recognizes as the dangers of archaeology as a tool of empire.

The real-life Nazis were, of course, infamous for coopting archaeological practices in service of the state. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Nazi-sponsored archaeological digs took place throughout Europe and North Africa to further the racist ideology of the Third Reich and destroy or suppress any material that did not support their imperial doctrine.

One of the Third Reich’s primary endeavors in these expeditions was to find any evidence that would support the myth of an ancient Aryan race, the pseudoscientific theory first popularized in the 18th century by French aristocrat Joseph-Arthur de Gobineau, among others, and operated as a central ideology of the Third Reich.

Nazi archaeologist Hans Reinerth, the head of the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce, one of the Nazi Party organizations tasked to appropriate and loot cultural property, was explicit about such an agenda:

German archaeology is for me … indigenous, blood-bound Germanic and Indo-Germanic prehistory. Our spadework has the preeminent goal …of illuminating our hitherto neglected indigenous prehistory. Anyone who opposes this effort … is a pernicious threat to the German people and should be fought accordingly.

Such expeditions were also intended to justify the state’s territorial aggression and expansion. For instance, after Hitler invaded Poland in 1940, Wolfram Sievers, the managing director of Ahnenerbe, another SS organization that sought to find evidence to justify Nazi racial superiority, had the idea of sending a representative to Poland to seize any material that would retroactively establish the Nazis’ right to the land and endorse the annexation.

But while the crimes of Nazi archaeology were numerous, as archaeologist Bettina Arnold warns in her study of race and archaeology in Nazi Germany, what the Third Reich was doing was neither a “uniquely German phenomenon nor something we can safely relegate to the past.”

Modern archaeologists are forever disavowing how the Indiana Jones franchise equates Indy’s treasure hunting to serious academic archaeology to distance the fictitious looter from their field. (There’s a great McSweeney’s list that jokes about the many… many reasons Dr. Jones would have been denied tenure as a professor in mid-20th century America.) But Indy’s wont of looting priceless artifacts is also part and parcel of the history of Western colonial plunder conducted under the auspices of archaeological research.

Even Jones’s creator, George Lucas, first described Indy as “a grave robber,” hired by museums “to steal things out of tombs and stuff.” And despite in-movie quips by Indy’s museum director friend in Radars of the Los Arc about how he’s sure that everything Dr. Jones acquired for his museum conformed to the fictional “International Treaty for the Protection of Antiquities,” the museum was always more than happy to take the stolen goods Indy procured for it.

This story remains true to the real-life history of acquisitions, even following the landmark 1970 UNESCO convention that pioneered international return and restitution of cultural property.

“When I first entered the world of curators, it was the Wild West, ‘1970’ notwithstanding,” as Gary Vikan, a curator who came up in the 1980s, told the New York Times last year in an essay suggesting that the “Indiana Jones Era Is Over” for U.S. museums. “Curators and museum directors wanted to get important works,” Vikan continued. “You wanted to be the one that gets that icon, that sculpture, that bronze.”

While the repatriation movement to decolonize museums has continued to gain steam leading to the introduction of more legal protections for cultural property, from the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 to the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects in 1995, countless national treasures—from the Benin Bronzes to the Elgin Marbles—remain separated from their countries of origin. As human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson pointed out in his 2019 book, Who Owns History? Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure, “mighty ‘encyclopedic’ museums, like the Met and the British Museum” continue to “lock up their precious legacy of other lands, stolen from their people by wars of aggression, theft, and duplicity.”

The latest Indiana Jones movie, interestingly, takes place in 1969, just one year before the watershed 1970 UNESCO convention. But the ethics of looting were already established before Indy came up in the field, as evinced by British Prime Minister William Gladstone’s condemnation of the seizing of treasures from Maqdala in Northern Ethiopia in 1868. Addressing the House of Commons, he said he “deeply lamented, for the sake of the country, and for the sake of all concerned, that these articles … were thought fit to be brought away by a British army.” Going back all the way to 70 CE, Roman magistrate Gaius Verres was already being put on trial for plundering Greek temples during his reign as governor of Sicily.

Indiana Jones’ favorite lament—“That belongs in a museum!”—should ring hollow today. But though the Indy era may be ending at the box office, whether the “Indiana Jones Era” of museum practices is truly over, as the Times crowed, has yet to be seen. That same Times article also included musings by critics who bemoaned the loss of “treasures that showcase a country’s artistic brilliance from an international capital like Washington, where they are much seen, and send them to remote, uncertain settings.” (Whether they mean the metropolises of cities like Cairo, Lagos, and Santiago is unclear.)

It suggests there’s a ways to go before the chapter of pillage and plunder glorified by the Indiana Jones franchise fully closes. But with the new release debuting this holiday weekend, at least we can still enjoy Ford, now 80 years old, continuing to do what he does best: dodge snakes and perform the important public service act of punching Nazis.

Send A Letter To the Editors