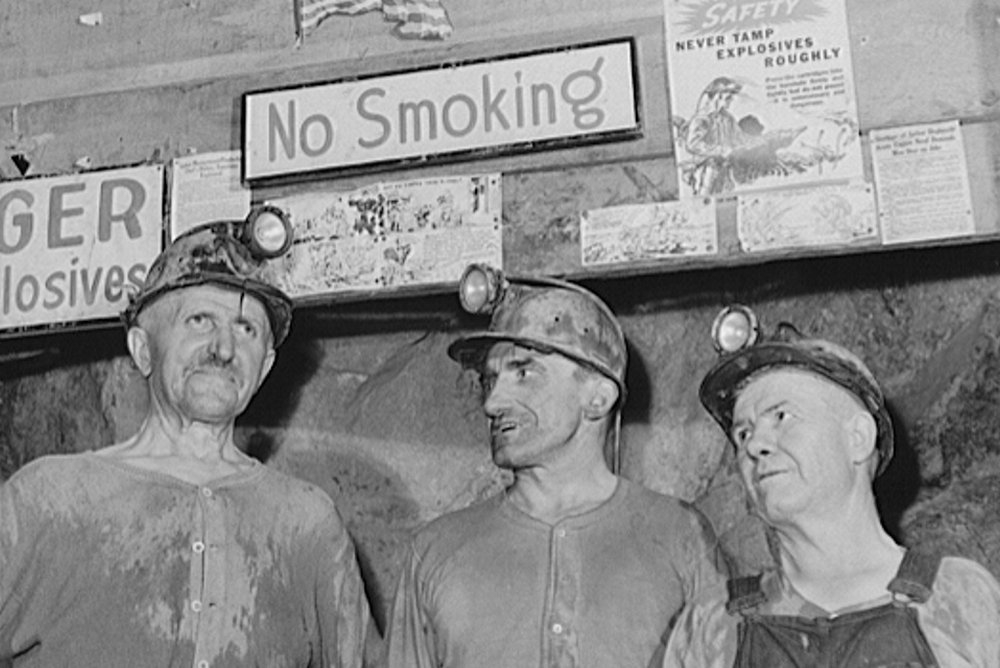

The Anaconda Copper Mining Company stretched from Montana to Chile. Labor and mining historian Ángela Vergara considers the mining towns developed around commerce—and what it might teach us about fostering sustainable communities. Above, company miners in Butte, Montana. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

In the Western U.S. and the north of Chile, large-scale mining has produced similar landscapes of extraction: open-pit and underground mines, smelter stacks, and large masonry structures. Transportation networks connected remote places to the world market, while many labor camps evolved into complex and vibrant communities. They also left their footprint on the natural environment: Polluted water and toxic fumes have made many of these sites inhabitable.

No other company left such a strong imprint in the mining regions of the Americas as the Anaconda Copper Mining Company—a “monstruous and complex organization,” in the words of historian K. Ross Toole—whose investments stretched from Butte, Montana to the Chilean desert. As the energy transition and its demand for lithium, cobalt, and other minerals drives a new mining boom, the history of Anaconda’s copper mining towns in Nevada and Chile can help us reimagine a just future not only in terms of how we power our lives, but in terms of fostering sustainable communities.

Though Anaconda’s history started in the late 19th century, much of the contemporary mining landscape dates to the boom that followed World War II, when growing demand, technological improvement, and massive capital investment, drove to increase production across the western hemisphere. As construction became more efficient, engineers spent considerable time perfecting the layout of crushing plants, smelters, and other facilities. At the same time, the company dedicated energy to perfecting the layout of workers’ domestic lives.

In the early 1950s, Anaconda started working in Yerington, Nevada. While many investors had tried to exploit the mines in the area with little success, in just two years, the company started producing cement copper at its new mine about 70 miles southwest of Reno. Isaac Marcosson, a journalist who wrote a 1957 history of Anaconda, called Yerington a “miracle” for transforming a “waste area” into a “productive community.” Its facilities included an open pit mine, metallurgical plants, and a townsite for workers called Weed Heights. Yerington was part of Anaconda’s larger corporate network. The mine required sulfur, which was brought from the Leviathan mine, some 50 miles away on the eastern slope of the Sierras, and its copper was sent to Montana for smelting and refining.

In the late 1950s, Anaconda built a modernist fantasy at 7,500 feet of altitude in the Chilean Andes. Chilean and foreign visitors marveled at the mine’s efficient organization and its perfect layout. While buses transported people back and forth to the mine, the ore moved quickly from the mine to the crushing plants to the concentrator. Before traveling to Anaconda’s elaboration plants in the United States, El Salvador’s copper took its final shape at the Potrerillos Smelter.

The designs of both the Yerington and El Salvador mines reflected ideas about efficiency and modernization that were coming into vogue at the time. In April 1960, Anaconda board president Clyde Weed wrote in the Engineering and Mining Journal that El Salvador was a great engineering achievement made possible by the combination of “capital, technical skills, and modern specialized equipment” and the “willingness of Chilean workmen.”

The mines, however, left permanent scars on the land, “ugly reminders of the visual and environmental price of extracting resources,” in the words of geographer William Wyckoff. In the north of Chile, Anaconda had started dumping copper tailings in the Pacific Ocean as early as the 1930s, destroying the local maritime life and embanking the bay. Yerington closed in 1978, shortly after Atlantic Richfield Company bought Anaconda. Like other abandoned open-pit mines, its pit quickly filled with toxic waste, leaving Nevada and Environmental Protection Agency authorities trying to sort out responsibilities and devise a cleanup strategy.

Workmen from an Anaconda smelter in Montana. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

Despite these environmental tensions, Wyckoff reminds us not to forget that mines “have also been places of work that produced paychecks and built communities.” People fostered a sense of belonging in isolated places and under harsh conditions, building homes even as their lives were marked by backbreaking work, violence, and conflicts.

In the 1950s and ’60s, narratives of technological progress and efficiency also included workers’ living quarters. Historically, mining companies relied on the company town model, whose replicable urban grid and company-run social services promised order that would increase worker efficiency and avoid tensions that could undermine production. But many of the old camps fell short of expectations, and company abuses, control, and material limitations created sparked conflicts and strikes.

The new camps built in the 1950s attempted to remake the company town model by improving living conditions. Anaconda called Weed Heights the “most beautifully constructed and maintained mining camp in the United States”—an attractive place to raise a family, own a home, and pursue the American Dream. Rent was low, and residents could apply for a one-, two-, or three-bedroom house. Built at the height of what the historian Lizabeth Cohen refers to as the “consumer republic,” shopping areas guaranteed residents access to consumption in all forms: restaurants, sports, and recreation. There was also a ballpark, sports courts, and a swimming pool. “Neat” and “order” frequently appeared in the town’s descriptions.

Similarly, in El Salvador, the company’s architects wanted to avoid the “industrial look” and “develop an attractive, modern town that would be a highly desirable place to work and live.” Workers’ duplex houses, made of concrete blocks and painted in pastel colors, contrasted with the arid landscape, while the curved streets gave the illusion of an American suburb. By the late 1960s, the town had about 8,300 residents and, in addition to the curving streets of duplex homes, infrastructure that included a modern hospital, a school, and stores.

The Anaconda era was tainted by its projects of social engineering, its anti-union practices, and impact on the environment. Living conditions were better than those of many other working-class suburbs, but geographical isolation and managers’ control over the living and working spaces created many tensions. In Chile, the Cold War political climate and the attitude of U.S. corporations created sharp divisions between managers and employees. Conflicts were common, and strikes lasted for weeks at the time. In 1971, the Chilean government nationalized U.S.-owned mines, including Anaconda’s properties.

Today, few mines consider building permanent camps or invest in local communities. Instead, they prefer to bus in workers, establish commuting systems, or offer temporary dormitory-style lodging near the worksite. These practices have created new problems, such as long and dangerous shifts and workers isolated from their families for extended periods of time. In places like Chile, the low-income communities that surround mining complexes have become sacrifice zones, areas that are heavily dependent on mining-related informal jobs and commercial activities and that bear the harsh environmental consequences of extraction.

Rethinking mining booms in a time of climate change and job insecurity should start by incorporating input from a diverse array of voices, including labor unions, environmental activists, businesses, and local populations. Only through working closely with communities directly impacted by mining can the transition to renewable energy truly create a sustainable future.

Send A Letter To the Editors