Summer camps have always been song-friendly places, carrying tunes that were fun—and that could also inspire hope, promote solidarity, and raise spirits, writes songwriter Shelley Posen. Illustration by Be Boggs.

At a children’s summer sleepaway camp in upstate New York in the mid-1920s, two young staffers, Artie and Larry, write a song for the annual camp play. It begins:

I love to lie awake in bed

Right after taps I pull the flaps above my head

And watch the stars upon my pillow

Oh, what a light the moonbeams shed.

Some years later, Artie—composer Arthur Schwartz—is writing numbers for a Broadway revue and gets stuck for a melody. He remembers his camp song, ditches the lyrics (written by Larry—Lorenz Hart—who is by then collaborating on Broadway musicals with Richard Rodgers) and gets wordsmith Howard Dietz to come up with new ones. The result is a hit and quickly becomes a pop standard that will be covered by Crosby, Sinatra, Bennett, Darin, Dylan, and many others:

I guess I’ll have to change my plan

I should have realized there’d be another man

I overlooked that point completely

Before the big affair began

Not all camp songs are written by such illustrious songmakers, nor have such a celebrated destiny awaiting them. But many songs sung at North American summer camps did and do become standards—in the lives of thousands of former campers who can still sing them years later and will remember them fondly all their lives.

What is a camp song—and why do they endure? Unlike “I Love to Lie Awake in Bed,” most of them don’t get composed at camp, nor is camp their subject.

For those of us who spent our summers at camps around Ontario, Canada in the 1950s and 1960s, “camp songs” were the songs we sang, year after year, in the dining hall during “singsongs”; in canoes on three-day trips; hiking in the woods; on bus rides; around campfires after the marshmallows had been toasted; and in the rec hall during rainy day programs. Not to mention the naughty or subversive songs we sang when our counselors weren’t around—mainly seditious parodies and scatological songs that made us laugh.

We learned songs from the staff and from each other; we brought them from home or we made them up for shows and all manner of activities, and to make each other laugh. Favorites included “Little Cabin in the Woods,” “Fire’s Burning,” “Down By the Bay,” and “Boom, Boom, Ain’t It Great to Be Crazy.” What made them camp songs was that we sang them at camp—some, nowhere else—where singing was a natural part of each day.

The children’s summer camp movement was established in North American cities in the 1870s, driven by the growing perception that modern urban society, especially its poorer classes, would benefit physically, morally, and spiritually from a closer relationship with the rapidly disappearing natural environment. Within the next few decades, youth-serving recreational organizations such as the YMCA, the Boy Scouts, and eventually religious and immigrant organizations acquired tracts of rural, wilderness land and organized “wholesome” and active experiences there for urban youth. Besides sports, many favored what were then called “Indian”-themed and -inspired woodland activities, along with programs promoting their own organizational goals.

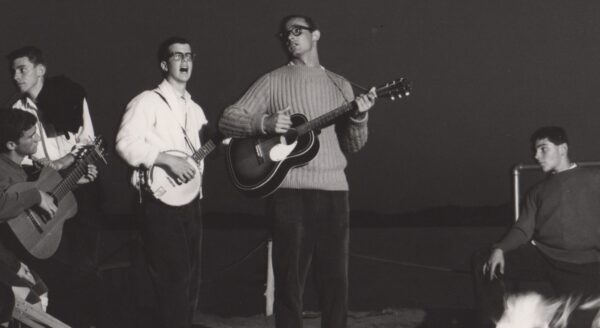

Author (middle left) playing banjo and singing at Interlochen Arts Camp in 1962. Courtesy of author.

It was an era when group singing was a popular, possibly universal pastime—in homes around a piano, in bars and theaters, and eventually in cinemas. What would be more natural, then, than to include it as an activity at camp, shaped to meet camp’s particular ends, be they recreational, religious, ethno-cultural, nature-centered, or socio-redemptive? Singing offered children self-made entertainment within the self-contained camp environment, and singing led by grown-ups was a superb collective activity for children. Singing could open and close a day, focus energies for rest hour after lunch, entertain in rainy weather, inspire hope or reverence around an evening campfire, promote solidarity, and raise spirits during team games.

From its inception, then, the summer camp was, or was made into, a setting friendly to song. Not all children’s camps may have been singing camps, but my bet is there was singing at every camp in some contexts, regardless.

Camp songs came in many different forms. They included the child-friendly—cumulative songs, make-up-each-verse songs, rounds, action songs with simple lyrics, and funny, silly themes—like “You Push the Damper In,” “There’s a Hole in the Bottom of the Sea,” and “Junior Birdmen.” Then there were the ones that were, paradoxically, not simple or funny at all, but youth-accessible and inspiring: songs of world peace and civil rights like “Listen Mr. Bilbo” and “We Shall Overcome.” Most of all, they had to be group-singable—with easy choruses (labor songs like “Union Maid”) and refrains (sea shanties like “Haul Away, Joe”), or call-and-response structures (“The Green Grass Grew All Around”), with harmony-inviting melodies (spirituals and folk songs like “When the Saints Go Marching In” and “On Top of Old Smokey”).

Many of the songs that spring first to my mind as “camp songs” aren’t the usual ones. They are old pop standards from the Great American Songbook that we sang at Camp Katonim, a day camp near our summer cottage just outside Toronto, when I was 7 or 8 years old. At Katonim, singing was the day’s first activity. I walked into the dining hall, took a seat on a bench around the perimeter with 60 other kids and counselors, and joined right in as Joanie led us all from the piano. Occasionally, they were “kid-friendly” songs like “I Went to the Animal Fair” and “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour.” But mostly, they were what I later knew as my parents’ songs: “For Me and My Gal,” “Shine On, Harvest Moon,” “Side by Side.” They were great fun to sing, even if some of the lyrics were over my head. I came to understand them later, but I’ve remembered them ever since, and even just thinking about them takes me back, as camp songs do, to the place I sang them, and the people I sang them with.

Summer camp actually helped me become a musician. It was at camp that I learned to play the ukulele, then the guitar, then the banjo; as a counselor, I honed the song leading lessons I’d learned from Pete Seeger records. At one camp where I also taught swimming, the junior boys I bunked with came up with a chant they yelled after every dining hall singsong: “Well DONE Shel-DON Po-ZUN!” Soon, “Well Done” became my camp moniker, then a family nickname, and then—well, Well Done Music is the name of my recording label.

Like Larry Hart and Arthur Schwartz, I found camp the perfect place to create and perform music where music was welcome. Like them, I went on to other musical arenas, but in my case, camp songs and camp singing remained part of my musical life—whether on stage teaching a chorus to an audience, leading a choir, or making up a silly song with my granddaughter as I bounce her on my knee.

Send A Letter To the Editors