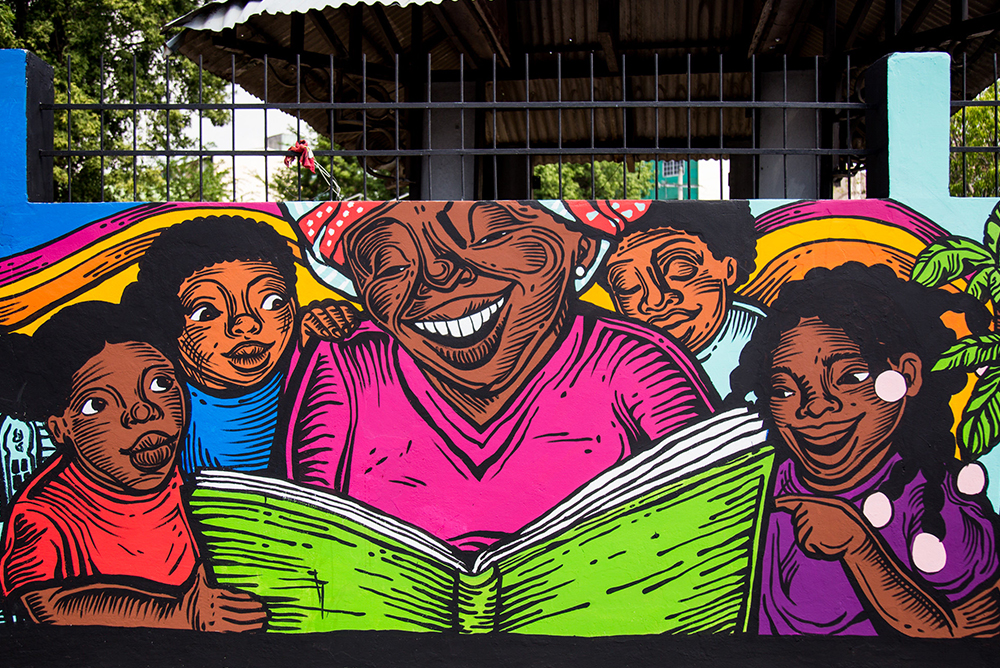

Wanting to understand the country of her birth, historian Kaysha Corinealdi interviewed Black elders about their lives and memories, developing decades-long friendships. Above, a mural by Martanoemí Noriega at the Museo Afroantillano de Panamá. Courtesy of Randy Navarro/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED).

In 2001, I made my first visit as an adult to Panama City, Panama. The city was both familiar and alien to me. My family migrated to the United States when I was 11, but our home—where my great-grandparents, cousins, and aunts and uncles resided, where I attended elementary school, and where I made my first best friends—had been in the province of Colón, on the Atlantic side of the isthmus. Still, I recognized the sounds, smells, and bustle of the city. I spotted the same type of diablos rojos that I would take from school to my great-grandmother’s house. But other things were new: multi-lane traffic, a bustling university campus, and more people per square mile than I had ever encountered as a child.

I was also returning to Panama as a college student with the explicit goal of learning more about this country that was my first home. I had my childhood memories, the stories known and retold in New York’s Panamanian diaspora, but I hungered for more. I wanted to understand how those who came before me had lived and understood their realities as Black Panamanians and learning about Panama City was an important part of the puzzle. By speaking with elders about their life histories and memories, I came to know not only the city’s present form, but its past as well.

My first meeting with Inés Sealy took place at the Museo Afroantillano de Panamá (the Afro-Antillean/West Indian Museum of Panama) in the predominantly Afro-descendant and working-class El Marañón, Calidonia neighborhood. The museum, inaugurated in 1980, is housed in a former mission chapel constructed in 1910. It offers visitors a capsule of the rich histories that Afro-Caribbean migrants and their descendants brought to Panama. It also feels like home, with bedspreads I recalled having seen as a child and images of Black women on the move that made me think of a regular day in Colón. But while the museum awed me, Sealy’s life story—which led me through multiple generations of Black migrants, entrepreneurs, and Canal Zone workers—stole the show.

Inés Virginia Sealy was born in Panama City on February 27, 1939. Her parents, both born in the British Caribbean, were among the nearly 200,000 migrants who arrived in Panama during the decade of the Panama Canal construction (1904-1914). Her maternal grandfather was among the 40,000 workers contracted by the U.S. government to build the canal, and her mother was just three months old when they made the journey from Saint Lucia in 1906. The choice to recruit from the British Caribbean was purposeful: these workers spoke English, but could be paid much less than U.S. citizens.

Sealy’s father also worked on the canal construction. He was 19 years old when he migrated from Barbados in 1909. He returned to Barbados after the completion of the canal—only to return to Panama five years later, as Sealy told me lightheartedly. Upon his return, he worked in the Canal Zone and in the military and civilian areas surrounding the canal, both “under his name and that of others.” After eventually formalizing his employment in the Zone, he worked there until Sealy graduated from high school, and then opened a car repair shop.

In 1938, he purchased the home in the Carrasquilla neighborhood of Panama City where Sealy was raised and where, in turn, she raised her own children. In Carrasquilla, Sealy developed close friendships with other Black Panamanians who, like her, spoke English learned from their Caribbean parents, despite being reprimanded for doing so at school.

Though both Sealy’s parents made Panama their permanent home, they chose to remain British colonial citizens instead of applying for Panamanian citizenship. Barbados and Saint Lucia remained British colonies until 1966 and 1979, respectively. There was a lot of “red tape” to becoming Panamanian citizens, including having to pass a citizenship test, Sealy recalled. Additionally, even if you obtained citizenship, it could be revoked. This happened to a contemporary of Sealy’s father, the Barbadian-born William Preston Stoute, who was one of the leaders of the largest labor strike to ever transpire in the Canal Zone.

When her 21st birthday came around, Sealy also had to consider the question of citizenship. According to the Panamanian Constitution of 1946, as someone with foreign-born parents, Sealy had to formally petition to have her birthright citizenship recognized. Applicants needed to prove their “spiritual and material incorporation” into the republic. “Had I known that it would be such a problem to become a Panamanian citizen, I would have applied for Barbadian citizenship,” she joked.

I was five months shy from my own 21st birthday when Sealy shared this experience. I wondered: Would I pass a “spiritual and material incorporation” test in Panama? Would I pass one in the United States? Sealy helped me understand that these processes were intended to exclude and make you question your belonging. Yet in time, that questioning made Sealy want to learn more about her family’s history.

Sealy visited Barbados four times. She did not find any living relatives—“When I was born my father was 48 years old; when I started looking I was 75 years old,” she recalled—she did find the plot where her paternal grandmother was buried. It was in the cemetery of Saint Christopher’s Church, which made a kind of cosmic sense to her, because, her father “when he attended church here [in Panama], did so at Saint Christopher’s Church.”

Sealy followed in her beloved father’s footsteps by working in the Canal Zone, where her English skills made her a desirable candidate. She began in a temporary position as a sales clerk in one of the commissaries, but tenaciously applied to every opening and job-skills test available. “All of us Black women [in the Zone],” she recounted, “were trying to move up in our job positions.” Eventually, she found a permanent post in the Zone library system, where she remained for 23 years. All the while, she continued to further her education, taking classes in library studies at the Universidad de Panamá.

But this education and training didn’t suffice in the face of the Zone’s entrenched race and citizenship hierarchy. Anti-Blackness shaped daily realities in the Panamanian Republic; in the Canal Zone white U.S. citizenship trumped all else. When her superiors promoted a white woman born in the United States—someone with less education than Sealy had—to effectively become Sealy’s boss, she decided she’d had enough. She retired at the age of 48, benefiting from changes in the Zone labor laws that allowed retirement after 23 years of service.

In her long retirement, Sealy became a certified Spanish and English translator, helped coordinate calypso shows (including one featuring Lord Cobra), and volunteered her time with organizations like the Society of Friends of the Museo Afroantillano de Panamá.

My last in-depth conversation with Inés Sealy was in August 2019, 18 years after our first meeting. There was an epic aguacero that day, with lightning, downpours, and the threat of the electricity giving out. But still, we spoke for hours. I had plans to spend more time in Panama in April 2020, but the pandemic changed everything. We chatted briefly on Zoom, and I told her I was applying for grants that would allow me to spend a full year in Panama starting in Fall 2022. Sealy urged me to come sooner. Our elders are leaving us, she warned.

I imagined that I had more time, at the very least with la Señora Sealy. In her 80s, she was still making moves all around Panama. I had to keep up with her. But then she passed away on June 5, 2022. It was just a month before I was finally able to make it back to her city—a city she had helped me understand and love.

When I visit the Museo Afroantillano, I still imagine I will see Inés there. The way I understand and experience Panama City is indebted to the elders like her, who helped me travel from the past and into the present and allowed me to appreciate the ebbs and flows of the spaces that we end up calling home.

Send A Letter To the Editors