After the Louisiana State Penitentiary Confiscated My Language Book and CDs, I Sued to Get Them Back

Several years ago, I decided I wanted to learn Italian. Since nobody I knew spoke the language, I decided to buy a book and teach myself. I scanned a few issues of the Edward R. Hamilton book catalog until I found exactly what I wanted: Barron’s E-Z Italian, which promised to help “develop your conversational skill and listening comprehension in Italian.” The book, 296 pages cover-to-cover, came with four companion CDs at the affordable price of $14.95. I placed the order.

For many people, ordering an Italian instruction book would be no big deal. But I was—and still am—in prison, in Angola, Louisiana. Conducting correspondence from here is hard, and that includes getting access to books.

My internet access is nonexistent. My communications with the outside world are limited to phone calls, the U.S. Mail, and a dedicated electronic messaging service for incarcerated people. Corrections department policy determines what I am allowed or not allowed to send and receive, and officers in the prison mail room monitor and inspect everything. Ordering a book, even a seemingly innocuous one like E-Z Italian, can get complicated.

A few weeks after I ordered my book, I received notice from the prison’s mail/package room that my materials had arrived but were confiscated as “unauthorized items.” No other information was provided.

I promptly filed a grievance. This is something I do rarely, only when I feel prison actions are egregious, and demand correction. I had been allowed to order the package and pay for it, I noted, and should therefore be allowed to have it. Weeks passed as the system slowly geared its way toward addressing my complaint. When a response finally came from the deputy warden’s office, the written reply indicated that inmates were prohibited from learning, teaching, writing, and otherwise communicating in a foreign language. So, no, I could not have the book and CDs.

This seemed absurd. I went to the prison library and searched Angola’s official policies, procedures, and directives. I saw evidence of no prohibition against receiving foreign language material. I started to log the various cultures at Angola that utilized their native languages in casual conversation and in the presence of other prisoners and guards—Spanish, Vietnamese, Cajun French. From the reading library, I compiled a list of foreign language texts that were available to the general population, including an entire section dedicated to Spanish language; textbooks on basic French; and even a Russian dictionary. I found that the penitentiary’s Bible college taught its students basic biblical Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. In short, foreign language was everywhere.

I noted all of this in a second step grievance, which went to the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections secretary in Baton Rouge. The department should be pleased that I wished to broaden my educational horizons, I noted in my complaint. And realistically, how Italian could I become from a $14.95 study course? A few weeks later, a letter from the department arrived: The secretary was backing the warden’s opinion, in its entirety.

I ran into the deputy warden of programming at the next Angola Prison Rodeo. He was no stranger, and he was not a bad guy. I said, “Are you going to let me have my book?” He just shook his head and replied, “You know they won’t let me do that.” They, as in the warden. He told me the warden did not want a bunch of prisoners speaking in languages his officers could not understand.

“Okay, well,” I said, “I’ll see you in court.” I wanted my materials, I was entitled to them, and principle dictated that I fight for them.

I filed my suit on my own, in Louisiana’s 19th Judicial District Court in nearby St. Francisville. I asked not only that my confiscated property be forwarded to me, but also that policies be promulgated to force the penitentiary to allow any prisoner to access educational foreign language material. My legal argument was founded in the First Amendment right of access to publications, as well as the absence of any administrative, local, state, or federal prohibition against a book like E-Z Italian, and the fact that the facility allowed me to purchase the book before confiscating it.

A corrections department lawyer met with me prior to my scheduled hearing, several months later. She was pleasant, but on a mission. “Are you sure you want to go forward with this?” she asked. I said I was. She said the warden really wanted to put the issue to rest. I told her to give me my book and she wouldn’t hear from me again. Through it all, I made clear that all I wanted was my material.

The corrections department held out all the way to the morning of the hearing, minutes from appearing before the magistrate, before finally caving. Their lawyer presented a form through which I could agree to drop my suit in exchange for the confiscated package. I signed it. The magistrate appeared disappointed. He seemed poised to grant me relief, and sanction the corrections department and the penitentiary.

I was okay with my decision. I had proven that the policy was wrong, and without legal standing. The warden would think twice about intercepting other people’s language books from now on. And if he did, I had one hell of a lawsuit already drawn up to fight back.

A day or so later I received my package. It was worth the wait. I made it about a third of the way through the book, learned a lot, and eventually moved on to other projects.

Months passed, again. One day I received a letter from the clerk of court: a copy of a notice to the defendants in my suit—the prison—that court costs and fees in the amount of $900-plus were overdue.

I got a huge laugh out of that. My little $14.95 Italian language course cost the corrections department nearly a thousand dollars. I’m still proud of that.

As they say in Italian, te l’avevo detto. I told you so.

John Corley is associate editor of the Angolite, the news magazine of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. He is the author of two collections of poetry, and a recipient of a National Council on Crime and Delinquency journalism award, and PEN America fiction, playwriting, and poetry awards. His work has appeared in the Atlantic, BleakHouse Review, and Hanging Loose.

I Want to Expand My Knowledge. The Arkansas Department of Corrections Keeps Getting in My Way

The prison where I’m incarcerated is part of the Arkansas Department of Corrections (ADC). But that’s a misnomer. Like the biblical Pharisees who created elaborate rules to exert their moral vision, such as prohibiting shoes made with nails or tacks on the Sabbath because it supposedly violated the Day of Rest, ADC likes to create schemes to prohibit—not “correct.”

One of their most elaborate schemes amounts to a war on books. Their line: Books are security risks.

Books and reading are my life. If I am not busy on my unpaid work assignment, I’m either reading or writing, and I have the books I study with sent in. The prison does have a library that I use but it is comprised mostly of genre fiction and is a poor source for educational or research material.

Since I am always trying to expand my knowledge and my creative writing skills, I often buy books specific to what I need. I own books published by Writer’s Digest, and written by authors such as Roy Peter Clark and Patricia T. O’Conner. I have PEN America’s The Sentences That Create Us. Books are my team—they help me in my quest to become the best version of myself.

Books I have tried to buy have been rejected on several occasions, always deemed a “security risk.” You might imagine I was ordering books detailing industrial locking mechanisms, or explaining how to organize dissent groups, or perhaps books on how to brew alcohol or concoct mind-altering substances. You’d be wrong. The security risk usually amounts to some type of fuzzier suspicion, or moral objection.

One book I ordered and was not allowed to receive was 400 Things Cops Know, which I intended to use as research for a novel I wanted to write, a character-driven story about a small-town cop who becomes embroiled in the discovery of horrible secrets. It’s about the struggle of doing the right thing despite family loyalties. This was not a book on police secrets or procedures. It had more to do with their humanity and the way they dealt with people. That the system would deny me such insight confirms my belief that these people really do view me as beneath them. How dare I obtain insight into the social workings of police officers!

I put the project on hold, but rather than waste my investment and allow the book to be destroyed by the prison, I paid extra (scarce) money to ship it to my sister in Michigan. I never actually saw the book. My sister never received it, either.

Another rejected book was Beautiful You by Chuck Palahniuk. The prison allowed me to order and receive three other novels by the same author: Fight Club, Choke, and Diary. But Beautiful You was a “security risk.” I suppose the adult advisory warning on the book must have alerted some prude that the novel contained a plot about sex toys. I’m 57 years old in an adult prison. How dare I possess such immoral material!

Recently I was notified that I had received a gift of books from (I think) Lucy Parsons Prison Book Program, which is based in Massachusetts and sends books to incarcerated people. The prison sent a notification that evidently, one of the books has a stain. It’s been flagged for review, which means that it will likely be rejected—and probably the three other books in the package as well. The stain becomes the security risk, not the other way around.

ADC’s “morality” is undermining efforts to make my life and this narrow world bigger, richer, and more meaningful through reading. It is tossing wet blankets, and clouding over a beacon of hope. My struggles to read books are just another challenging part of an existence in which fear and disappointment kindle fires I already struggle to extinguish.

Richard Beebe is incarcerated at the North Central Unit in Calico Rock, Arkansas. He started writing while in county jail in 1987; most of his stories are still unpublished, but he writes them anyway. He is compiling and polishing poems for a chapbook, IT TAKES A VILLAGE.

There, Reading Material Gets Caught in a Web of Arbitrary Rules and Regulations

My paternal grandfather was a mailman. Early in his postal career he drove a mail vehicle pulled by horses, who knew his route and would stop at each farmhouse. My grandfather was often the only visitor farmers got all day.

Perhaps because of this family history, I always understood distant communication as a normal, vital part of life. It was a way to correspond with people you knew. More than a utility bill, mail provided information, and a social connection.

At the Shakopee prison, we receive mail Tuesdays through Saturdays. Mail is the highlight of many incarcerated people’s day.

There are a million rules governing what we can’t receive—strange things, such as “Latin phrases,” (see endnote 1) and less surprising things, such as “descriptions or illicit use of weapons.” There is a list of unallowable books, like Fifty Shades of Grey and The Art of Seduction (though this is rarely a problem). Most people get religious books, mysteries, and self-help books. A lot of Bibles and James Patterson.

Several of the mailroom rules end in “etc.” Sometimes it seems like the “et ceteras” cover everything.

If the mailroom does not give us our incoming correspondence, they send us copies of a form that indicates the reason why. But for all the mailroom rules, it feels like we get things (or not) based mainly on the whims of mailroom people.

A lot of times, when I’m waiting on a book, the form says I can’t get it because there’s no receipt. The prison wants this because we aren’t allowed to acquire debt while incarcerated, and a receipt shows the bill is paid. To me, it’s just another et cetera.

This battle is real. When a purchased item arrives without this documentation, we have 30 days to find a receipt before the mailroom disposes of the book (or calendar or journal). My husband Dan knows to print off a receipt when he buys me a book, and send it to me. I tell other people to check off the “gift receipt” box on online orders, and write a little message (without Latin phrases!) if possible—it seems to help.

This has a personal benefit, too. It is a big bummer to get a book and have no idea who sent it. How can I send a thank you when I don’t know who a gift was from? It forces me to play an ugly game of Nancy Drew. Who knows my birthday is in mid-December? Who knows I love Masha Gessen? I hate having to write, “I received two books last week and don’t know who they are from, so if they were sent from you, thank you. They look great.”

I feel sentences like that make people who didn’t send me a book feel bad.

We worry a lot about things, in prison.

The receipt issue is a problem for my writing, which has been published in books. When editors send me a copy of a book or a magazine with my work in it, the mailroom won’t give it to me—they only pass along magazines that have been purchased by subscription. Do I really want to bother (a kind and busy) magazine editor and ask them if they want to send it again? No, I do not. I’m not a rude person.

Three months ago, my non-incarcerated friend, Holly, sent me copies of several Department of Corrections policies, printed off the state website. They were not delivered to me. Reason given: “Published material not received directly from the publisher/authorized vendor, or not paid in advance via offender accounts.”

I wrote the mailroom and asked why I could not have access to the information. I am supposed to be able to get copies of corrections department policies for free from our library, up to 50 pages.

The short ending to this story was: Two weeks later I received most of it. For the long, asinine version, please refer to endnote 2.

Every institution seems to have its own protocol. At my friend Sean’s prison in Wisconsin, they only get their mail after it has been shipped to Phoenix, Maryland; photocopied, and reshipped back to Wisconsin.

I ask myself, “What are they so afraid of?” God forbid someone might send in a secondhand book, or a letter with a coffee drip stain, a Bible without a receipt, or an article about work release (all materials I’ve seen rejected).

Just imagine what a person with a DWI on their record, or who has suffered with a heroin addiction, could do with all that.

1) Apparently this rule is not strictly enforced. I create collaborative poems with Sean, who has been known to slip in Latin phrases wherever he can fit them in a stanza. These get delivered.

2) Holly filed a complaint with the ombudsman for corrections on February 2, She wrote:

On January 23, 2023, I mailed nine identical packets of information in manila envelopes to inmates at MCF Shakopee, and one more identical packet to an inmate at MCF Stillwater. On January 25, 2023, each of the nine at MCF Shakopee received the empty manila envelope and a notice that the contents could not be delivered and were confiscated as contraband. The notice did not include a list of the contents, and each of the nine was given a different reason for defining the contents as contraband, such as that the contents were “brochures” or “published material not from the publisher,” and a few people were given no reason at all. MCF Stillwater delivered the entire packet to the inmate there without issue.

The contents included in the packets were Department of Corrections Policy 205.120 (printed out); Minnesota statues 243.05, 244.065, 609.185; a PDF of a work release flyer from the Minnesota Department of Corrections website; a work release fact sheet from the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee; a news article written by an inmate, and a government study about work release.

On January 25, 2023, Holly called and spoke to a mailroom officer at Shakopee who claimed she recognized Holly as a former inmate and said she “had no business calling there to question her.” Holly asked to speak to a supervisor and left three voicemails, which were not returned.

I wrote this to the mailroom on February 5, 2023:

I was denied access to mail sent to me 1/24/2023. The items in question were sent by a non-incarcerated person.

I noted that the main source of these papers was the DOC website. Nothing shady.

Why am I prevented from hearing about DOC policies? Why can’t I have access to this information?

A mailroom officer wrote back:

You definitely are not prevented from seeing or hearing about DOC Policy. I believe you can get all the information you want on policy in the library. We have spent time this week speaking with other facilities and have determined we will allow the DOC copies however not the photocopy of the IWOC Brochure as that policy firmly states only the publisher or Authorized Vendor may send. If you wish to appeal this part, please follow the chain of command.

I write this horrifically boring addendum to show how slow and stupid every little thing is, in prison.

Elizabeth Hawes is a recipient of a grant from the Ridgeway Reporting Project for Incarcerated Journalists, and is working with her friend Sean on Convergence, a collaborative writing project involving incarcerated poets across America.

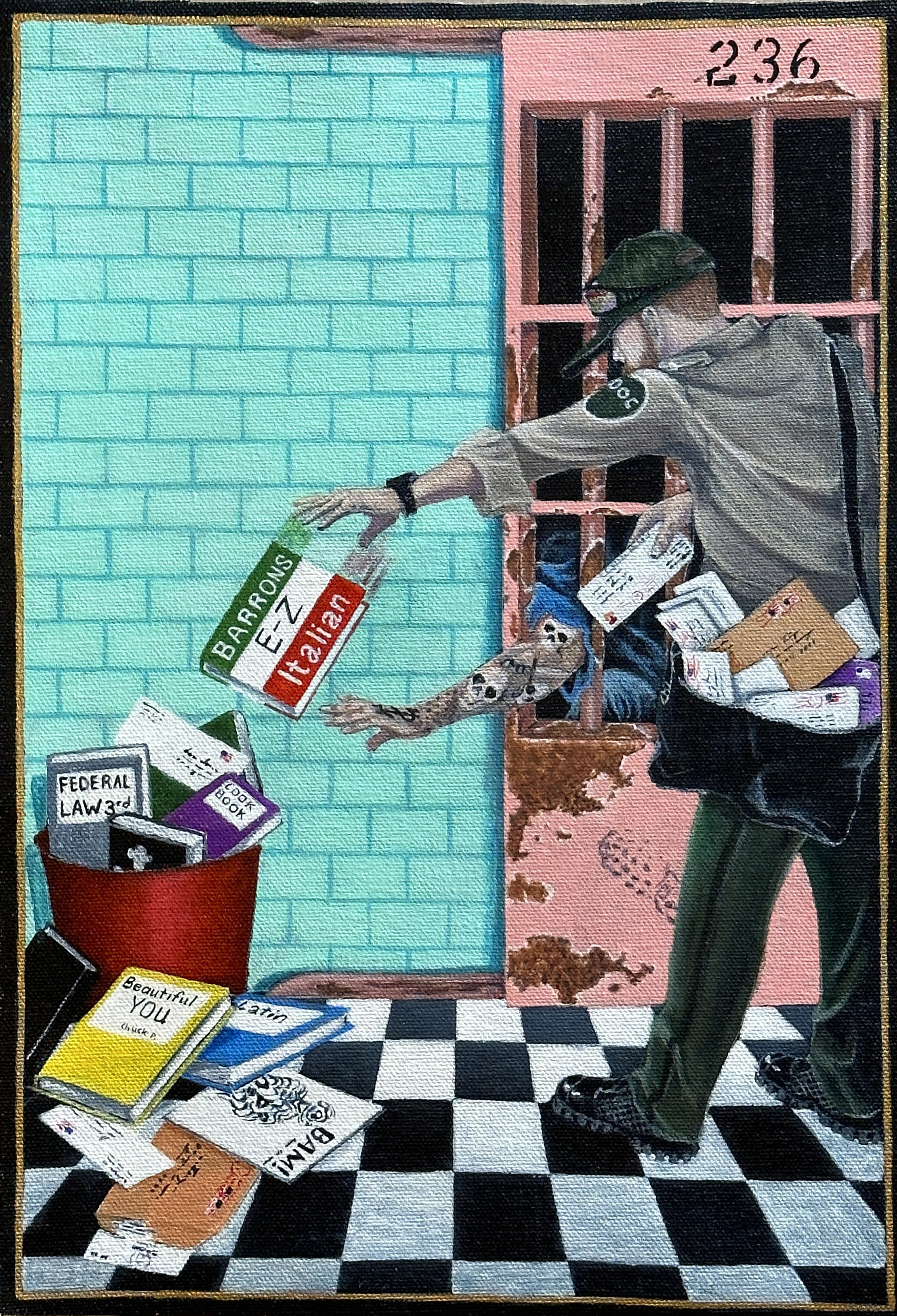

Empowerment Avenue connected us with incarcerated artist Alvin Lavon Smith Jr., who addresses the theme of these three essays in his painting “Mail Call.” Below is a note he attached with his work:

I am exceedingly grateful for the opportunity to create a piece of art that speaks to an issue so personal, and so near to my heart. As someone who’s been incarcerated now, going on 30 years, I’ve experienced firsthand the crushing weight of being denied access to the information contained within particular books. To look forward to teaching yourself something through the power of the written word. Only to have that hope dashed by petty policies that are effective only at preventing self educating from within prison institutions.

I’ve dealt with this issue many times myself. The most recent being, as a member of the Empowerment Avenue community, I was blessed with subscriptions to two art magazines. The first, Apollo, I received without delay. The second, BAM! (Black Art Magazine) was denied because even though it was purchased through Amazon, it was shipped from “a third party” publisher. Being a Black man who’s an artist myself, I’m sure you can understand why I’d want to venture past the cover of that particular magazine.

Sure, BAM! is not an educational book on its surface (though I could make a strong case otherwise), each time this happens it reminds me of something I once read. A slave master becoming aware that his wife had been teaching his young slave Frederick Douglass how to read, he quickly put a stop to it! He admonished his wife saying, “If you teach… him to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.” Hearing what was said to the mistress of the house, young Douglass understood that education was his path to freedom.

Causes one to ponder: Is there some other agenda behind the denial of reading material? Perhaps, these materials could make us unfit to be convicts.

Alvin Lavon Smith Jr. is an incarcerated visual artist in Michigan’s Department of Corrections. He was born in Laurel, Mississippi, and grew up in Ypsilanti, Michigan. He’s a participant in the University of Michigan’s Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP).