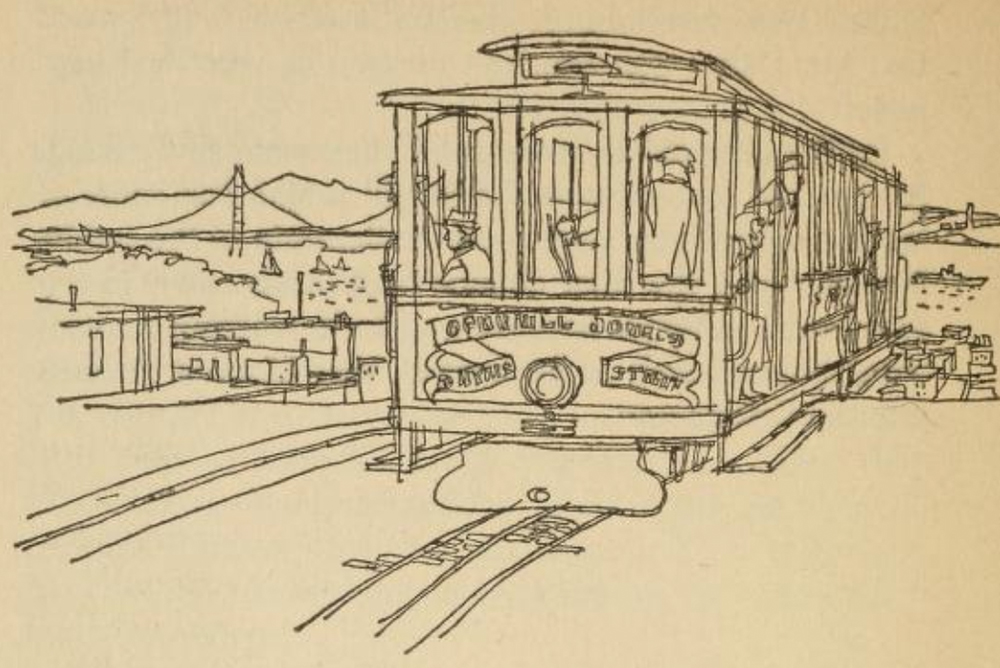

Phyllis A. Whitney’s Mystery of the Green Cat led writer Larry Gordon to develop an affection for San Francisco. Illustrated by Leslie Goldstein, from Whitney’s book.

For a young bookworm like me in 1960s New Jersey, almost nothing was more exciting in elementary school than ordering my own paperbacks from the Scholastic Book catalog. I would carefully select books from a paper form distributed in class. A few weeks later, paperbacks arrived at school in wondrous boxes. Best of all, they usually had nothing to do with schoolwork. I read them in bed or in a park, on winter nights or summer days.

Those novels took me places, out of my crowded, insular hometown. My family often visited nearby Manhattan but that was still off-limits for solo wandering. Children’s and young adult literature let me imagine independence—meeting new people and exploring different places on my own. One book in particular, Mystery of the Green Cat by Phyllis A. Whitney, led me to develop an affection for that distant, hilly city on the Pacific coast: San Francisco.

The little paperback’s romantic portrayal of the City by the Bay grabbed me and never let go. It’s a depiction that pushes back against the rampant San Francisco bashing in vogue today. I fear that San Francisco has gotten such a bad rap—borne of an often brutal, and mainly conservative, narrative about the city—that people have lost sight of its unerasable allures, and its irreplaceable spot in American history and culture. It’s important to remember the things that made, and make, San Francisco great—not for the sake of nostalgia or adolescent literature, but to ensure that a dark fog of disdain doesn’t block out everything else.

Of course, parts of downtown San Francisco do face huge social problems—homelessness, drug addiction, shoplifting invasions. But Fox News, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, and many other critics persistently push an exaggerated portrait of the city as a hellhole, where car thefts and fentanyl deaths, corporate flight, and retail closings fuel a so-called Doom Loop. As the city loses tax base and tourist revenues while gaining pathologies and street crime, they predict the end is near.

Too many seem to gleefully dance on what they hope will be the grave of a city they always resented for the scary things it represented politically, sexually, artistically. San Francisco is home to beat poetry, hippies, gay libs, Big Tech, Nancy Pelosi, political correctness, and pricey and beautiful architecture that made its critics’ own pale hometowns look like dumps—so now is the time to avenge all that.

They never mention that San Francisco rebuilt itself, heroically, after the 1906 earthquake and fires that had leveled it. It re-emerged as a magnet and cradle for talent and creativity, punching above its weight in music, art, literature, technology, medicine, alternative lifestyles, and stupendous business success. It can survive its current troubles.

It may sound childish to inject a middle-grade mystery book into a debate about today’s painful, intractable issues. Still, in gentler times, Mystery of the Green Cat, first published in 1957, celebrated San Francisco. Whitney, writing for kids all over the country, displayed a skill, unburdened by kneejerk politics, that unearthed the magic of the place.

Whitney presents a vision of a pre-hippie S.F. that is obsolete, or maybe never existed. Still, who could resist it? Was it real? At least some of it was and is.

Recently, I decided I wanted to revisit that place, and I went looking for Whitney’s book. My original copy was long lost, but I ordered a used one from an online book dealer. I re-read its 188 pages, in large typeface. It was an odd time-traveling experience, allowing me to consider my own pre-teen brain and realize how little of the book I accurately remembered other than its general vibe.

In the book, a widow and her two young daughters move to San Francisco to live with her new husband, a widower, and his two pre-teen sons. Family conflict ensues. Meanwhile, in the spooky Victorian house just up Russian Hill, two elderly and mysterious sisters keep a bunch of Asian relics and a batch of secrets. The frailer sister keeps asking for her missing green cat, which turns out to be a little statue containing a life-changing note from her long-dead husband.

Its plot is underwhelming to the Adult Me, but then the plot was never important to me as a kid. The book’s real star is the city itself. I loved the way its young characters explored San Francisco’s foggy beauty and pastel ethnic neighborhoods. Eleven-year-olds hike around Chinatown and Coit Tower, ride cable cars, and snoop around old mansions, library archives, and antique shops—without grownups. Dramatic hills surrounded by water, tugboat hoots from the bay, and bridges that defy gravity grabbed me.

“The view up here was tremendous,” Whitney wrote of Coit Tower on Telegraph Hill. “The streets of San Francisco went straight away beneath the tower and straight up the opposite hills, as if somebody had ruled lines on a piece of paper, paying no attention to the heights… The little houses clung to steep cliffs, their gardens gay with birds and flowers. It was like another world – a suspended, arboreal sort of world.”

At Fisherman’s Wharf: “There were so many boats that their spars and masts stuck up like a toothpick forest … Crabs were cooked in kettles right on the walks.”

I first visited S.F. when I was in college, in 1973, as a guest of a Los Angeles friend who drove me up the coast through Santa Barbara, Monterey Bay, Big Sur, and finally across the Bay Bridge. I was far from a country bumpkin, but the sight of the skyline over the water was thrilling. We hiked up hills and clung to poles on cable cars’ outer ledges. San Francisco’s lovely mixture of urbanity and nature seemed more humane than New York’s noisy swagger and scary decay.

Later, my work as a journalist brought me to S.F. many times. I stayed in high rise hotels with views of the bridges, to my delight. Covering higher education, I persisted through interminable University of California regents’ meetings knowing that, after deadlines, I might eat in Chinatown and shop at City Lights Bookstore.

I am always impressed by how there is no place in the nation like San Francisco, a benefit of its unusual topography and its spirit of social openness and innovation. This, with a surprisingly small population of less than 900,000. Some people tout its European, walkable vibe, an antidote to suburban sprawl. But I would argue that San Francisco is a most American place in its soul. I think about the Midwest servicemen who passed through in World War II and returned for a better and more interesting life. Gold Rush miners, jeans manufacturers, rock and rollers, immigrants from Asia and Latin America, refugees from sexual repression, IT brainiacs—they all embraced San Francisco and many successfully staked their claim on the American Dream.

Of course, my childhood enchantment was somewhat naïve, and my adulthood love for the City by the Bay has been tempered by reality. Over the 1970s and 1980s, San Francisco’s counterculture wilted and darkened. Haight-Ashbury became dangerous. The AIDS epidemic was a horror. Big Tech brought in money, but widened inequities and pushed rents beyond the reach of the artists and writers who had given San Francisco its bohemian flavor. Whitney could not have anticipated the grief of today’s homeless encampments, with so much suffering met with insufficient responses.

Yet, despite its current problems, a wonderful, beautiful city still exists amid the fog. It is worth fighting for. In Whitney’s book, the widow discovers a redeeming message inside the pottery cat statue—a note from the past, delivering solace. More important, for me, are the messages about San Francisco’s allure infused through my little paperback: “Fog drifted through the streets of San Francisco, so that every road looked wavery and mysterious, and even ordinary houses took on a ghostly aspect.”

That still happens. I still love it.

Send A Letter To the Editors