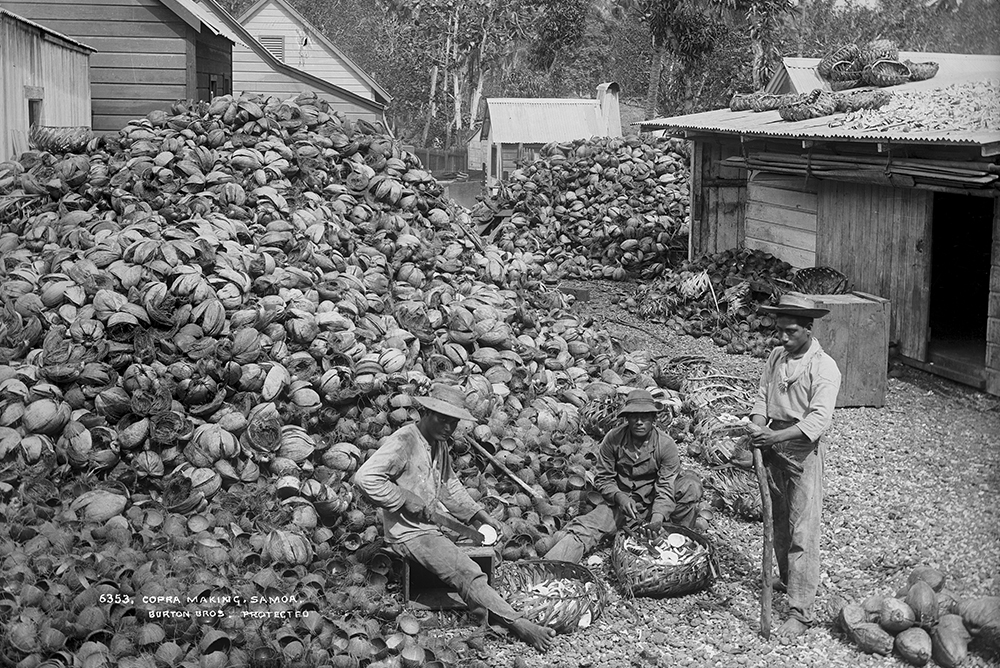

Samoan cooperatives helped coconut farmers resist colonial rule and seek greater economic self-determination, writes historian Holger Droessler. Large piles of coconut husks and shells from the copra-making process in Samoa. Courtesy of Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa.

Coconuts are everywhere. If you walk into a grocery store pretty much anywhere in the United States, you’ll find a cornucopia of coconut products: coconut water, coconut oil, coconut macaroons, and, of course, husked coconuts themselves.

Most consumers spend little time thinking about where the coconuts in this “coco craze” come from. But according to a Samoan proverb, “The coconut is sweet, but it was husked with the teeth.”

For the Samoan farmers and workers of the early coconut industry, these sweet treats were a site of struggle against colonial rule and exploitative plantations. By launching cooperatives, Samoans proved themselves savvy participants in the expanding global coconut trade while seeking economic self-determination. Recalling that fraught history is a reminder of the importance of worker power in contemporary global supply chains—where many of the same inequalities persist.

Americans got their first taste of coconuts just over a century ago. In the mid-19th century, the U.S. Navy began eyeing the South Pacific islands of Samoa as a coaling station. Around the same time, British and French missionaries along with German traders opened the first trading stations in Samoa. They moved methodically to monopolize the import and export of goods essential to the Samoan economy, and by the late 19th century, coconuts and copra—the dried meat of the coconut—had become Samoa’s main export to Europe and the United States. There, the copra was processed into a variety of products, including high-quality soap, margarine, and even dynamite.

From the start, Samoans resisted the Euro-American monopoly of the lucrative copra trade. They quickly realized they were being cheated by outlanders. After weighing out copra at trading stations, Euro-American traders routinely paid Samoan producers 30-50% less than they should have.

In response, Samoans took out large lines of credit and endlessly deferred their payments, knowing that the lack of effective legal enforcement of debt defaults protected them from punishment. They also resorted to manipulating the quantity and quality of the copra they delivered to traders by soaking the copra in water or mixing in greener nuts of poorer quality.

holding on to their community-based farming practices, and succeeded

in protecting long-standing ways of life.

The U.S. Navy established formal colonial rule over eastern Samoa in 1900. The next year, hoping to raise revenues and increase copra production, the cash-strapped naval administration introduced a copra tax. In the eyes of U.S. officials, requiring taxes to be paid in copra protected the “child-like” Samoans from exploitation by unscrupulous traders.

Samoans were slow to pay this new tax. Many Euro-American traders even tried to keep the Samoans from cutting copra to pay taxes rather than sell it to them for export. By 1902, Samoans still sold copra below market price, keeping the prices artificially low as long as the naval government used the copra taxes to finance its operations. “In some villages,” Governor Uriel Sebree noted, “the natives have already resolved to sell wholesale rather than individually, and thus get a higher price.”

In 1903, the naval administration cut out the pesky traders and took over the sale of copra. From then on, Samoan producers brought their copra to government-run stations and received a standard price per pound somewhat lower than the projected annual bid. This margin allowed the government to pay expenses such as transportation and wages for the stations’ clerks. After the year’s copra output was awarded to the highest bidder—generally an American or Australian firm—any remaining surplus was returned to Samoan family chiefs. But instead of cash, they received copra receipts that could only be used to purchase goods in official stores.

By and large, Samoans did not object to the U.S. government’s takeover of the copra trade, because it increased their profit margins. Just the year before, Samoan copra producers had founded their own copra cooperative. In an effort to outcompete foreign traders, cooperative members from the main island of Tutuila and the smaller Manuʻa Islands 75 miles to the east pooled production and distribution of copra.

For a few years, the producer cooperative worked well. The company operated stores in several villages across the islands and owned three motorboats to ship copra to Pago Pago for export to San Francisco. Most importantly, the cooperative protected Samoan copra production by adding a crucial distribution mechanism. But because it allowed its Samoan members to buy goods on credit, company debt continued to rise.

By 1907, rumors of embezzled funds and skyrocketing debt led the U.S. naval government to become a trustee of the company. Then, on the brink of World War I, U.S. officials determined that the cooperative had failed economically and should be shut down as soon as remaining debts were collected. As Governor C.D. Stearns summed up with characteristic condescension, “The natives are absolutely incapable of managing their own affairs in financial matters and it is believed that permitting them to establish co-operative stores and co-operative schooners has been a mistake.”

Yet what looked like failure to paternalistic U.S. officials in Pago had provided Samoans in Manuʻa with a much-needed way to pool resources and mitigate risk. For the moment, they refused to let the cooperative venture sink.

As it turned out, the cooperative did not survive much longer. In January 1915, a tropical cyclone devastated Manuʻa. Half of the 1,500 inhabitants of the islands had to be relocated because most of the food crops had been destroyed, along with the majority of the cooperative’s copra stock. It took several years for agricultural production in Manuʻa to recover, but the copra cooperative never did. By 1919, the former store of the cooperative had become a naval dispensary and wireless radio office. The following year, the Manuʻa Cooperative Company officially folded.

While the cooperative movement eventually collapsed under political coercion, it helped form the nucleus of a more sustained challenge to colonial rule in the 1920s. To protest Navy mismanagement, American Samoans organized a copra boycott and practically shut down the naval government, which depended on the taxes drawn from the sale of copra.

Faced with Euro-American coconut colonialism, Samoans resisted by holding on to their community-based farming practices and succeeded in protecting long-standing ways of life. At the same time, they adapted selectively to the new colonial world by founding cooperatives whose worker mutualism aimed for greater economic self-determination.

Remembering the deep colonial roots of coconuts—and many other products—on American shelves helps put current frustrations, whether about stocking speed or quality, in perspective. With colonized workers serving American consumers, early 20th-century coconut production in Samoa carried the seeds of today’s global division of labor. Then as now, American consumers should push for worker control over the means of production and distribution of the tropical fruits they have come to love.

Send A Letter To the Editors