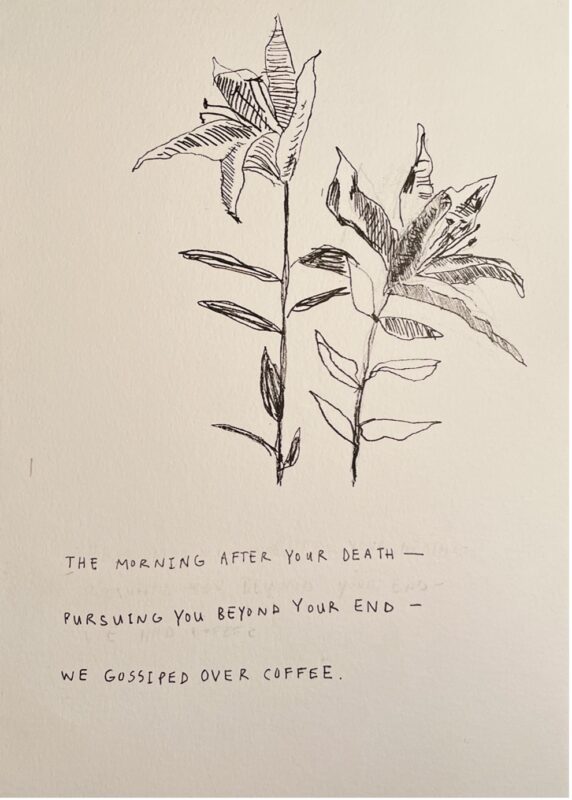

My first instinct when my grandma died was to purchase and draw flowers for her. A traditional gesture of sympathy, the flowers seemed fitting—but the circumstances were unprecedented.

It was April 2020. My grandma was exposed to COVID in the memory unit of her nursing home and died within the week. Like so many families, we would not be able to gather to mourn her or to say goodbye in person.

I continued to buy flowers in the weeks that followed to enliven that cavernous spring. Time, or what I had understood of it, lifted away. The days blended together as I grieved my grandmother and the world that the pandemic had, at least temporarily, taken from us.

Gradually, the flowers and the act of drawing them proposed an alternative to this sensation of suspended or absent time: The time of cut flowers.

Two deaths punctuate this time. The first is swift and takes place when the flowers are clipped from the earth. The second death unfolds in the vase over the course of a week or so as the flowers shrivel, rot, and dry to a crisp.

The word “death” doesn’t fully capture this trajectory. What I’m describing, more precisely, is the process of losing life. At the same time, the opposite is true: Flowers are a sign of springtime, of renewal and rebirth.

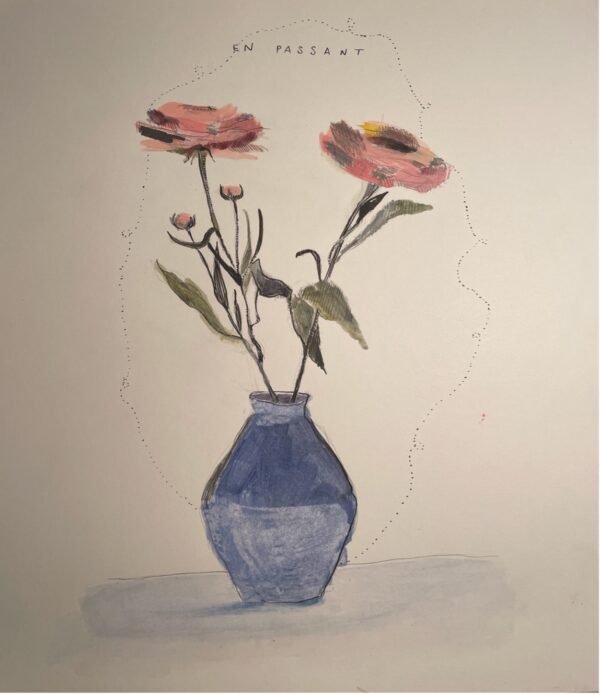

In between these two deaths is a period of intense intimacy. Trapped together in the vase, the flowers’ stems, petals, and leaves intertwine so that observers can’t always distinguish one from another. Of course, in this case, intimacy with one or several implies isolation and exclusion from others.

The flowers’ predicament seemed to echo our own in a moment so marked by literal and figurative deaths, suspended time, and enforced intimacy or isolation. My flowers coped with what was happening to them in different ways.

Two ranunculus I picked up at the farmers market ended up locked in a passionate—but doomed—affair. Their knotted stems and tightly bound petals encircled each other in a tragic embrace.

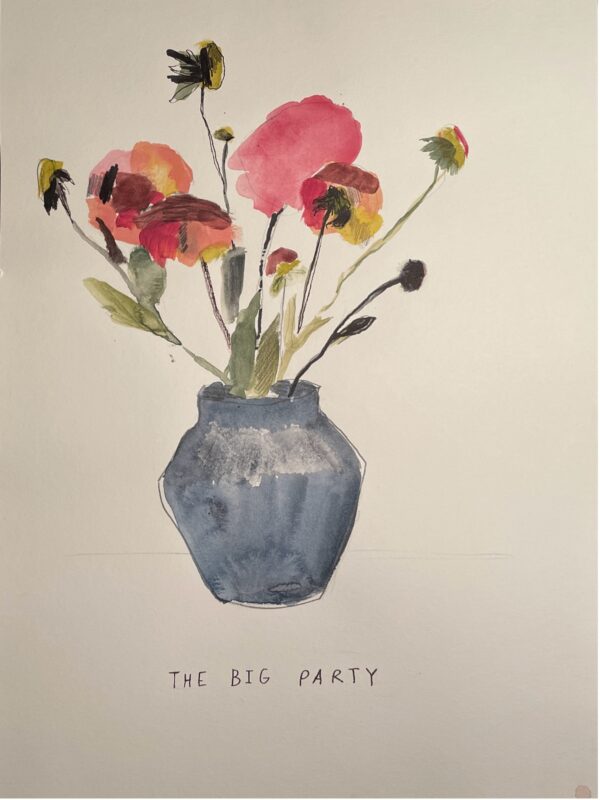

The peonies came next. Their petals unfurled with exuberance, without caution. They got too close to their neighbors, spilled their drinks, and fell out of their chairs.

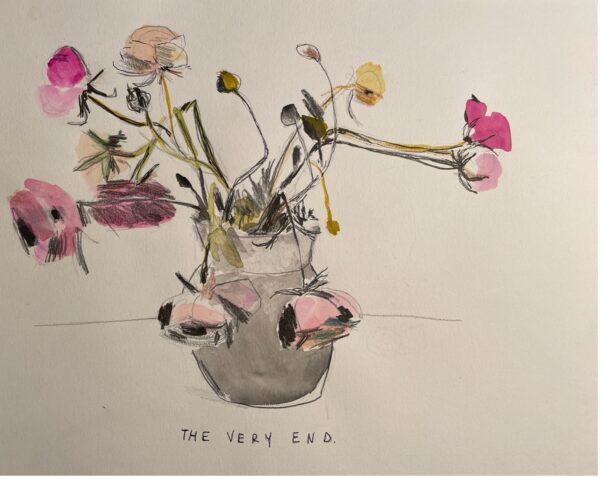

I painted the tulips too late. They were already wilting, tips turning yellow. Unable to hold their weight, the heads of the languishing flowers fell to the table.

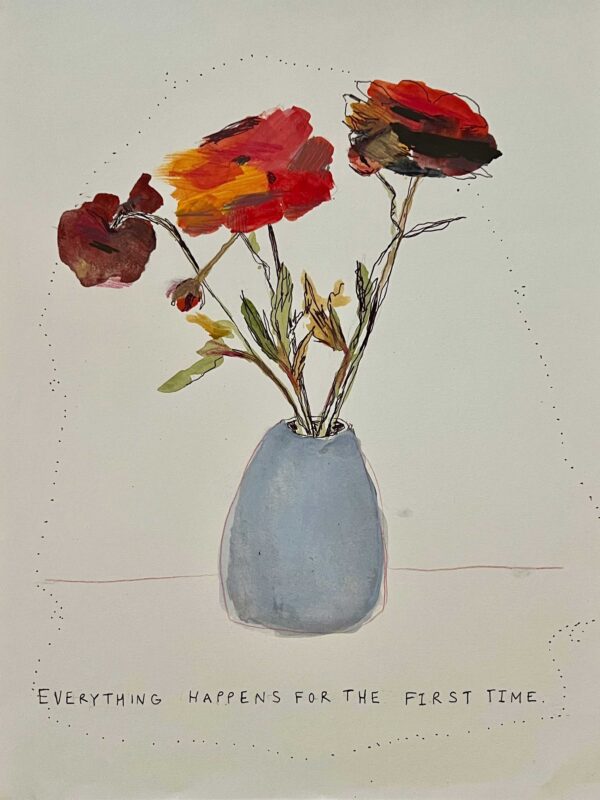

Was it really the very end? One particularly dreary week, a dear friend read me a poem called “The Joy” (“La Dicha”) by Jorge Luis Borges. “Everything happens for the first time,” Borges explains.

I fetched roses that Saturday.

If mourning is a time-bound process whereby the mourner assimilates their loss and eventually returns, perhaps somewhat transformed, to a state of “normalcy,” what happens when one wreckage piles on another?

The collective moment the pandemic summed has passed. The ritual of drawing cut flowers was part of that moment, when a quiet violence seized loved ones in the stifling privacy—rather, enforced isolation—of the home or hospital. The drawings aspired to mold a slow, shapeless, or even absent time into a coherent form.

Today, a global polycrisis consumes our attention. Time accelerates and seems to run out as each day brings more death and the failure to end indiscriminate killing.

In a moment of war and mass violence, watched from afar or experienced first-hand, we might imagine that the time of cut flowers plays over and over. This time, its repetition of loss and renewal happens loudly, in public, and with such speed that the boundary between the two seem to dissolve. Renewal, when it occurs, is experienced at the same time as mounting losses.

From this perspective, mourning loses its coherence: It does not take place after but during and always.

The time of cut flowers reminds us that the world, cherished or despised, never ends just once.

Send A Letter To the Editors