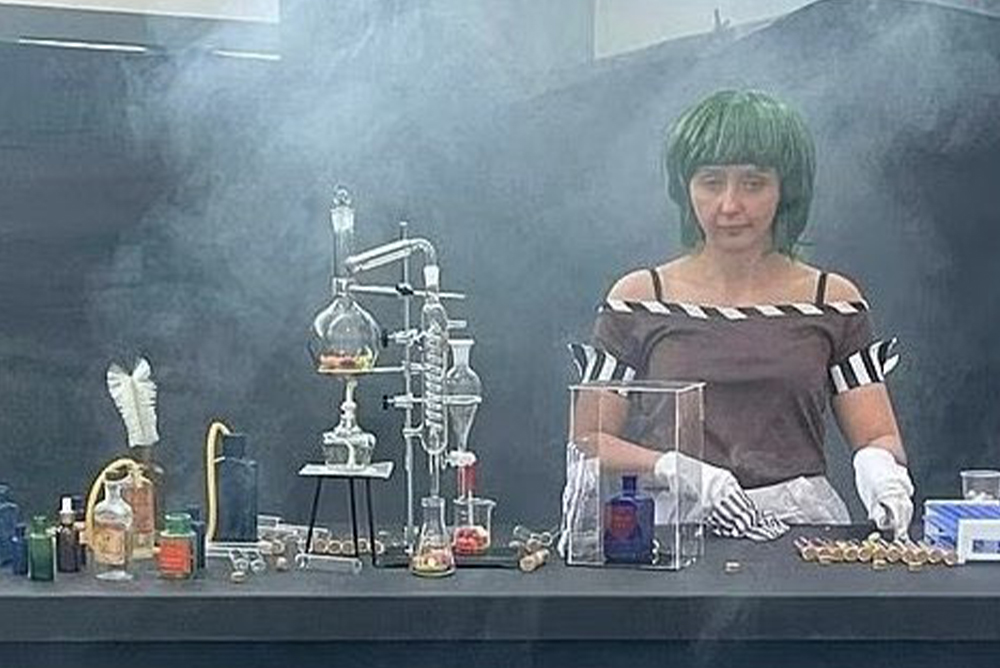

With the recent Willy’s Chocolate Experience debacle, columnist Jackie Mansky wonders: Why do we seek out immersive entertainment? A photo from Willy’s Chocolate Experience. Courtesy of @agneponx/X.

Last month, an “immersive” Willy Wonka event took over my news feed.

Normally, I’d keep scrolling.

Promoters market these voguish multisensory experiences—which are supposed to literally immerse you in an environment through projection mapping technology, virtual and augmented reality, sound, physical sets, and sometimes even actors—as “transformative,” “out-of-this-world,” and “sublime.”

I haven’t understood the appeal. The few I’ve tried out have fallen short of those ambitious statements. Far from offering a transcendent experience, they seemed gimmicky, not to mention overpriced.

But Willy’s Chocolate Experience got my attention, largely because the event, a debacle that reportedly ended in tears, could, in no credible way, pretend to sell awe by the $44 ticket price.

The company behind the production, House of Illuminati, had used generative AI to advertise a show where “dreams become reality.” But the projection equipment, the linchpin of these fantasyscapes that use light to turn any physical object or surface into a life-like display screen, didn’t arrive in time. That meant the kids who showed up for the event didn’t get to see “giant mushrooms filled with sweets,” “colossal lollipops,” or “candy canes that seem to touch the sky”—just a warehouse in Glasgow, Scotland, filled with a few props. Any illusion that they were taking a jaunt through Roald Dahl’s candy factory (or even its off-brand cousin) was shattered. Within hours, angry parents got the whole thing shut down.

The internet ate it up. For the next few days, visuals from the Wonkapocalypse, like a lonely plastic prop rainbow that resembled a Jeff Koons sculpture and an exhausted-looking actress hunched above a candy laboratory, were inescapable on my social media.

I watched as these posts about the breakdown of a constructed reality mingled alongside real news stories about the world we live in, at a historical moment where our shared sense of actual reality has catastrophically broken down. As all of this blurred together, it helped me to finally see what it is that people seek out in immersive entertainment.

I don’t think they believe they’ll find wonder there. But they know they’ll find a carefully curated escape from the present.

Our current immersive era, in this way, can be understood as the 21st century’s answer to the pleasure gardens of the past.

Commercialized pleasure gardens, seemingly natural spaces of leisure drenched in artifice, emerged in the 17th century as entrepreneurial English aristocrats opened up their private gardens to the public for the price of admission. Inside the walls of these manufactured Edens, artists created complex trompe l’oeil, which made two-dimensional surfaces on elaborate walking paths appear three-dimensional. Musicians played “fairy music” to establish a fantasy atmosphere, and over at Vauxhall, one of England’s grandest pleasure gardens, workers even imitated nightingale calls after the birds left the grounds in 1730. The ultimate act of fiction, of course, was that pleasure gardens created a space where commoners could brush elbows with the gentry.

Scottish author Tobias Smollett captured the feeling of entering one in his 1771 travel novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker:

I was dazzled and confounded with the variety of beauties that rushed all at once on my eye. Imagine … a spacious garden, part laid out in delightful walks, bounded with high hedges and trees, and paved with gravel part exhibiting a wonderful assemblage of the most picturesque and striking objects, pavilions, lodges, groves, grottoes, lawns, temples, and cascades, porticoes, colonnades, and rotundas, adorned with pillars, statues, and paintings; the whole illuminated with an infinite number of lamps, disposed in different figures of suns, stars, and constellations.

Like today’s high-definition floor-to-ceiling projections, light, as Smollett observed, played a crucial role in creating the mirage.

Pleasure gardens boasted thousands of colored lamps, called illuminations, as well as painted linen canvases backlit by candle or lamp light, and endless fireworks of all shapes and designs, according to Anne Beamish, a scholar of pleasure gardens. I was struck by how modern the stylish pyrotechnic displays feel in Beamish’s descriptions. “Some involved attaching fireworks to structures or devices that moved,” she writes. “Others relied on sheets of paper that were pricked and backlit. As the paper moved, an optical illusion gave the appearance of movement, such as falling water.”

In the 18th century, pleasure gardens hit their peak popularity worldwide. They attracted a new, rising middle class with expendable time and income, eager to trade the smog and stench of industrializing city life for a few hours of gilded fantasy. Working people could enter these walls of pretend, roam curated pastoral grounds, and experience the latest technological wonders of the day, like the hot air balloon.

Not everyone could buy a ticket inside, however. In the U.S., pleasure gardens were predominantly white-only. Still, there are records of Black pleasure gardens in New York, such as the African Grove, established in 1821. Two hundred years later, for a 2021 MOMA exhibition, the artist Tourmaline characterized the Black pleasure gardens as “spaces where people dreamed up and then practiced versions of freedom during slavery.”

Black pleasure gardens show that these grounds of amusement held the potential to be revolutionary. But more often than not, pleasure gardens ended up bound by self-imposed limitations. As cultural anthropologist Deborah Philips reminds us in Fairground Attractions: A Genealogy of the Pleasure Ground, they were created for profit. Because of this, she argues, they were constructed as “unthreatening and contained” spaces meant to “reassure rather than challenge.”

This is worth remembering as we enter a new age of immersion today.

Our modern inheritors of commercialized pleasure gardens can offer a dreamy respite to people eager to leave behind their worries for a few hours. But though they will continue to promise the world—or at least sights out-of-this-world—they are not set up to achieve such feats.

The Wonka experience’s empty warehouse is a good reminder that, by design, these new pleasure gardens can offer us little more than a trick of the light.

Send A Letter To the Editors