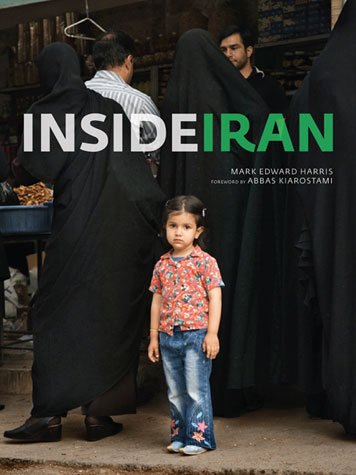

Inside Iran

by Mark Edward Harris

In Mark Edward Harris’ collection, Inside Iran, there are a handful of photos of the Iran of popular American imagination: oil refineries dotting a desert landscape; modest shrines to bearded martyrs; sandbags and guns near a nuclear site; women with stern eyes draped in head-to-toe black. But the great majority of Harris’ photos are of a different Iran – of children playing, families touristing, workers commuting. As filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami says in his forward, “I know those kids in the photographs; they are the same all around the world.”

Harris began his peripatetic photography career after his job taking stills for “The Merv Griffin Show” ended, along with the show, in 1986. Since then he has photographed dozens of countries, and released a similar collection of shots of that other point in the “axis of evil”, North Korea. In his introduction to this volume, he writes that he found it “important to see what people’s lives were like in a country whose future was likely to be played out in a geopolitical chess game.”

And so Harris travels to Tehran, capturing spots like the Milad tower, the Carpet Museum (which houses a rug depicting the U.S. presidents), and the tomb of Ayatollah Khomeini in moonlight. There are men selling snacks or praying in sock feet before a meal, children climbing on a playground emblazoned with a painted Mickey Mouse-ish character. Harris also ventures outside the capital, capturing historic monuments in the holy city of Qom, ruins at Persepolis, and the tombs of poets Hafez and Saadi in Shiraz. Mosques glimmer with turquoise tile; billboards and stenciled graffiti dot the old desert landscape. In Shiraz a young man wears a tightly-fitting shirt that reads “CIA”; Harris notes in the caption that men whose shirts fit too tightly are often targets for persecution.

The final photographs are of harsh mountainous western Iran – where Americans rarely travel and where Harris faced some scrutiny – the Caspian Sea, and the resort Kish Island, which Harris compares to Dubai because of its (slightly) relaxed rules and free trade. But it’s also surrounded by relics of the Iran-Iraq War, including Harris’ stunning final image, of a ship half-sunken since the 1980s, near which oil tankers routinely pass.

But more often he photographs artifacts of war, Harris snaps shots of women – always the symbol of Iran’s vacillations between conservative and liberal – in head scarves or full veils. Some are made-up, with manicured nails and dyed hair, and others are plainer. There are two elderly women among these photographs, full of verve, especially the one Harris captures in portrait. She runs a small roadside shop; her face is lined and her expression stern and wise. She is stock-straight and broad-shouldered in a thick mannish flannel coat. Harris’ most stunning images are these proximate portraits, of which he has a handful, of women with deep expressiveness, slight smiles and bright eyes. They are the precise counterpoints to the barren landscapes and oil rigs, full of vitality and peace.

Further Reading: Inside North Korea and The Soul of Iran: A Nation’s Journey to Freedom

Send A Letter To the Editors