We all hold prejudices of some kind, but the way we maintain these is telling. A person will attend to data that supports ideas he or she believes to be true, while ignoring evidence to the contrary. We’re perhaps most familiar with this in political discourse, but it intrudes on virtually every corner of human interactions.

Psychologists call it confirmation bias, and when my normally level-headed brother-in-law got caught in its trap a few years ago, the consequences could have been deadly.

In August 2010, I was backpacking with my brothers-in-law Ken and Robert, my son James, and Ken’s son Tim in the Wenaha Wilderness in southeastern Washington state. Summer in this area, a high plateau riven by a maze of valleys, is hot and dry. We stuck to upper elevations to avoid the heat of the valleys, but even on the ridge tops, temperatures reached the upper 90s, and there were few trees for shade. Water could only be found at a limited number of springs, scattered at intervals of five to eight miles along the trail.

One afternoon, we set out after lunch on a five-mile hike to McCain Spring, where we would camp for the night. The guidebook noted that the side trail that would take us to the campsite and spring was easy to miss, and the next decent water source was another four miles beyond that. With packs weighing 50 pounds each, we made our way under the hot afternoon sun through a long downhill stretch of dry scrub and yellowed grass.

I am an obsessive map-reader, and I worried that we would somehow miss the obscure turnoff to the spring, wondering how we’d find it in the jigsaw puzzle of valleys projecting out to the east.

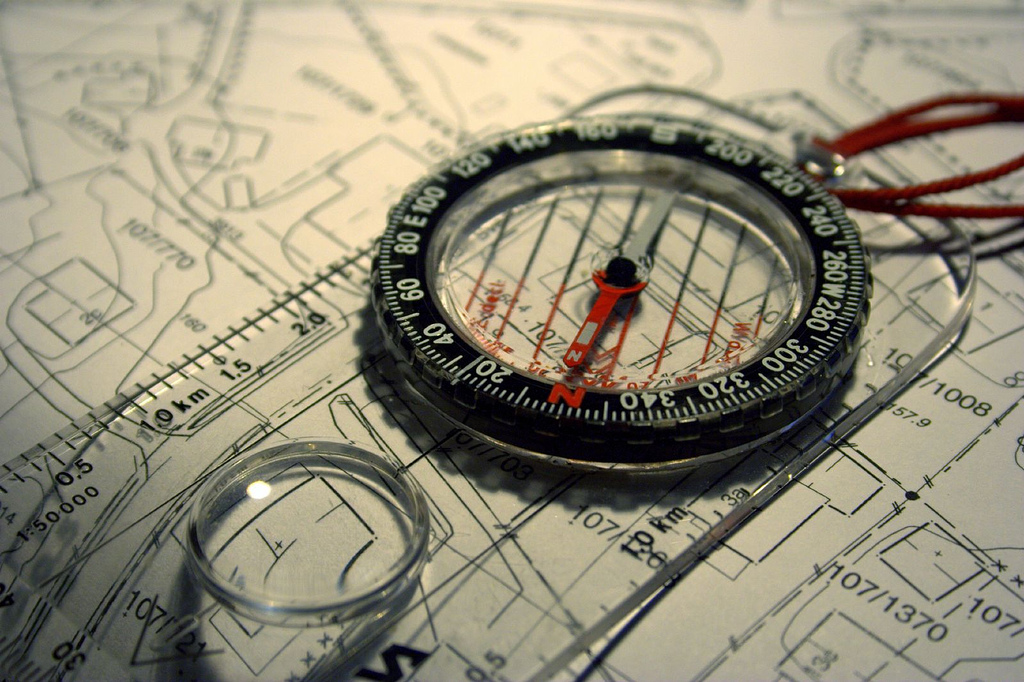

Each time we stopped near a lone tree, I would dart into the shade, pulling out my map and compass. I tried to triangulate against the distant peaks to see how far we’d come. I got the impression that my brother-in-law Ken was growing increasingly annoyed by my time-consuming attention to the map. In an irritated tone of voice, Ken asked me to get up and get back on the move.

On the map a landmark named Danger Point matched a rock formation with a steep drop-off. I pointed this out to Ken. He dismissed my identification. He was certain that we hadn’t traveled that far, that we could not possibly be about three-quarters of the way to McCain Spring. It had only been two hours since our lunch break. I was not completely sure who was right. I just let the two possibilities hang side-by-side in my mind. Searching for more clues, I spied a small saddle and a copse of trees in the distance that seemed to match the topography of the spring on the map. Again I pointed this out to Ken. Again he dismissed my claim.

Ken and I were approaching the question “Where am I?” in different ways. Ken based his estimate of our location solely on the elapsed time we’d been hiking since lunch. While I was thinking about the distance we’d covered, I also was comparing features on the ground to the map, continually updating my sense of position. Normally we hike at about one mile per hour with full packs, but since we were walking mostly downhill, we were moving substantially faster, throwing off Ken’s sense of location. Nonetheless, Ken’s sense of certainty and my view of his competence sowed doubts in my mind. When we reached the grove of trees I’d seen in the distance, there appeared to be a valley that led to the south. This seemed consistent with the map’s depiction of the flowage from the spring.

A trail led off downhill in the direction of the valley. I suggested that this was the spur trail to the spring. Ken was convinced that we were nowhere close. I pleaded with him. I suggested we drop our packs and reconnoiter. Why not let my son James walk for 10 minutes down the spur and his son Tim walk 10 minutes down the main trail? They would scout, return, and report back to us. Ken reluctantly agreed. He, Robert, and I waited at the junction.

As soon as James and Tim were out of sight, Ken became agitated and impatient. He shouldered his pack and walked off briskly in Tim’s direction. I couldn’t stop him. Minutes later, we heard a voice echoing from the bottom of the glade, “Hey, Dad, I found the spring.” When James returned, he asked anxiously, “Where’s Uncle Ken?” I told him what had happened. We waited 10 more minutes, but it was increasingly obvious Ken wasn’t coming back. He didn’t have enough water to reliably make it to the next water source.

James decided to give chase. Dropping his pack, he started jogging in the general direction of Ken and Tim. Robert and I took the spur down to the spring.

It was a wonderful campsite, used mainly by hunters in the fall but empty now, in late summer. Robert and I set up our tents and waited.

It was quite some time before James showed up with Ken and Tim in tow. Ken dropped his pack, looked around, and said this couldn’t possibly be the spring. He still was stuck on the idea that we could not have traveled this far, despite all the evidence in plain sight. I suggested it was at least a suitable place to spend the night. He relented.

Now it might be easy to fault Ken, but I think something else was going on. Certainly his reliance on a single navigational tool—elapsed time—was a contributing factor. The heat was a more insidious problem. Although none of us had a clear case of heat exhaustion, I think the afternoon sun bearing down on us steered our judgments, locking us into our own little prisons of thought.

The next evening a ranger on her evening stroll confirmed that the site was indeed McCain Spring.

I had already been convinced; Ken had not. After deciding we were in a different spot, he had focused only on the puzzle pieces that fit his preconceptions, ignoring other important clues. It’s the kind of confirmation bias we see all the time—and that we should be more vigilant about.

Send A Letter To the Editors