Raising literacy levels requires starting early. But how do you reach very young children, especially in a place like Salinas, where many parents are migrants who work long hours and don’t have enough time for their children?

Here’s one answer: Get their big brothers and sisters to help.

The two of us were graduate students in public administration at the Monterey Institute of International Studies when we found out about a program in Salinas called the Read to Me Project. We were struck by the simplicity and power of the concept: It places age-appropriate books in the classrooms of fourth, fifth, and sixth graders. The participating students—who have infant, toddler, or preschool-age siblings or children at home—check out those books and read to their younger siblings at least four times every week during the school year.

The program provides staff to motivate, support, train, coach and monitor each student’s reading. The two of us were curious about what the impact of this approach might be. Together, we conducted an evaluation of it as a capstone project for our academic careers.

Both of us were particularly interested because of the program’s location in Salinas, a place we know well and love. And both of us, in studying programs to serve people in the area, had been concerned about how some nonprofits can impose their agendas and values on local people. By this standard, the Read to Me Project seemed promising, since the concept was to get children and families to take the lead in exposing young family members to stories and books that would develop important pre-literacy skills to help children succeed in kindergarten and beyond.

We also knew the challenges that Salinas and its county, Monterey, face. Research shows that 80 percent of children here enter kindergarten lagging behind in “readiness” skills—vocabulary, language, basic knowledge, and comprehension—that kids need to read.

Many kids never have the opportunity to get ready. Seventy-five percent of children in Salinas do not attend preschool. Surveys show 48 percent of county families don’t read to children, and 45 percent of parents have less than a high school education. Many parents report not being confident in their own reading skills, or simply not having the time for extensive one-on-one interaction with their children.

The problem is not easily remedied. Research shows that children who fall behind in school often don’t catch up, with devastating consequences. Did you know that the vast majority of prisoners in this country are functionally illiterate? Or that two-thirds of those who can’t read by the fourth grade end up in prison or on welfare? An Annie E. Casey Foundation report, titled “Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation” and written by sociologist Donald J. Hernandez, tells us that students who do not read proficiently by third grade are four times more likely to leave school without a diploma than proficient readers. And this number increases significantly if the student lives in poverty.

Barbara Greenway, a public school speech and language specialist in the Salinas Valley, started the Read to Me Project four years ago because she was seeing so many underprepared kindergarteners. She started with a pilot project in the fourth grade classroom of her husband, a teacher, and it grew rapidly from there.

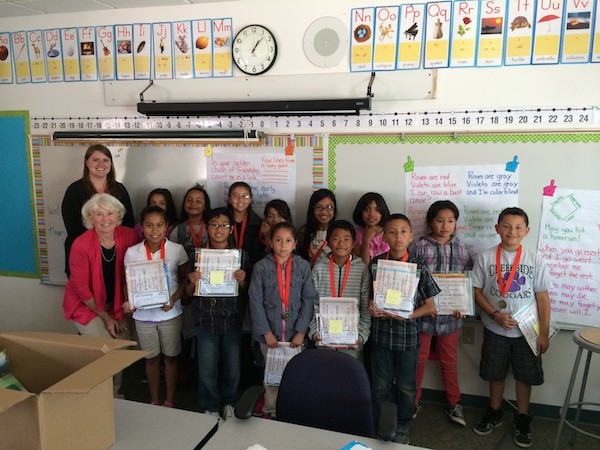

Today, the Read to Me Project involves 80 classrooms and more than 800 elementary students reading to 1,000 younger siblings across the Salinas Valley. And there are more people to serve. Of the 12,000 economically disadvantaged fourth, fifth, and sixth graders in Monterey County, some 4,000 have siblings under age five.

The program reflects the critical need for early engagement beginning at birth as indicated by research from Stanford professor Anne Fernald and the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. The research shows that by as early as nine months, a significant gap in brain development is already evident for children with what Fernald calls “inadequate opportunities for early learning.” By two years of age, children can already be six months behind in cognitive and thinking skills.

In the Read to Me program, the older students are trained in how to engage and read to children as young as eight months old. The strategies taught include knowing the book you read well, finding a quiet place, cuddling up beside your sibling, pointing to the pictures as you read, “making your voice interesting,” and having fun. When the program is first introduced in fourth, fifth, and sixth grade classrooms, students are taught about early brain development and the importance of reading to young children.

The participating classrooms receive a book bin filled with age-appropriate books for one- to five-year-olds for weekly check out. Reading to younger family members is assigned as part of nightly homework.

Young siblings may be read to for up to three years as participating student readers move through grades four through six. This continuity provides young children with extended exposure to early literature and increases the likelihood of successful outcomes and growth. The Read to Me Project also makes extra effort to encourage reading during the biggest gaps in the school calendar, by holding a holiday book wrap in December (where each student receives a book he or she can give to the younger sibling), and an end-of-the-year book bag giveaway in June.

As a positive side effect, family bonds are strengthened. The older siblings benefit by developing reading, speaking, and presentation skills. Research suggests they become leaders in their families, and become closer to their siblings. Some parents have told us that listening to their children read to younger siblings has improved their English language vocabulary; parents also may be more likely to read or tell stories to their children, usually in whatever language they feel most comfortable.

Most of the participating students report that they love reading to their young siblings. They often share stories about how their brother or sister will run to them when they get home from school and will open their backpack to find the book. Many students report that they no longer fight with their sibling and enjoy spending time with them. One boy named Teodoro, who lives in the Carmel Valley and whose parents don’t speak English, started as a struggling reader, but ended up checking out books weekly and reading more than 100 times to his 4-year-old sister. (He earned a medal from his school for this work).

This approach could—and should—be used elsewhere. It’s a classic case of “low-tech, high-effect technology.” The Read to Me Project supplies books, training, and support. The big brothers and sisters do the rest.

Send A Letter To the Editors