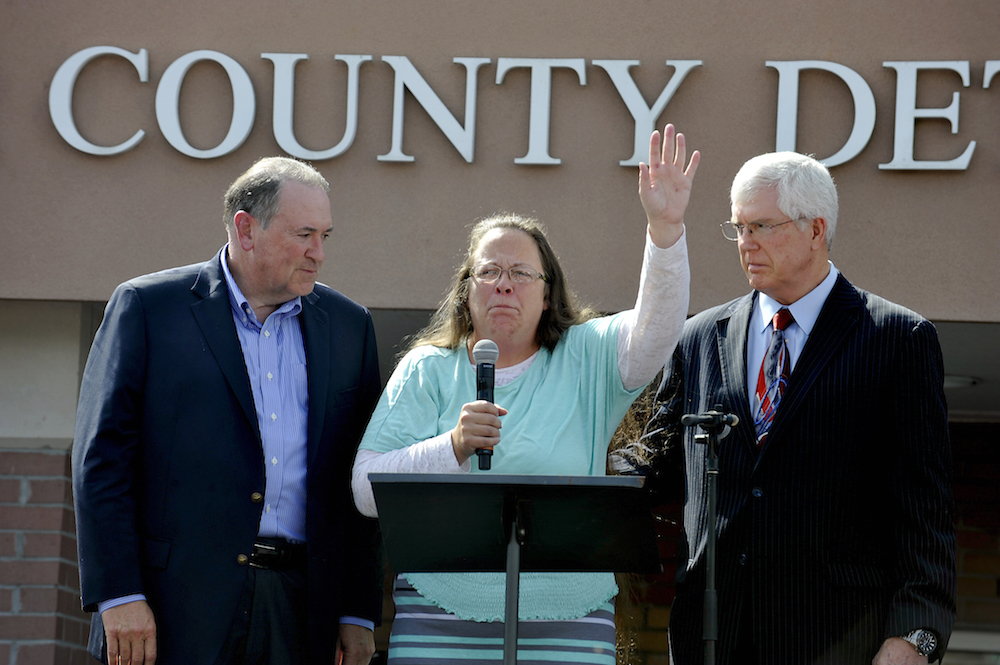

Kim Davis, flanked by Republic presidential candidate Mike Huckabee (L) and and Attorney Mathew Staver (R) speaks to her supporters after walking out of jail in Grayson, Kentucky September 8, 2015. U.S. District Judge David Bunning ordered her release after six days in jail, saying she “shall not interfere in any way, directly or indirectly, with the efforts of her deputy clerks to issue marriage licenses to all legally eligible couples.” REUTERS/Chris Tilley – RTX1RPQ3

We can say this of Kim Davis: She understands freedom of conscience. Standing defiantly behind the counter, submitting to federal marshals, emerging to a hero’s greeting with presidential candidates by her side, Davis understands that no law, no court, no other human being, can bind her mind and heart. The clerk of Rowan County, Kentucky, has grasped that being true to what she believes is more important than her professional future, her public image, her personal well-being. She has suffered for her beliefs, and in so doing she has followed a great tradition of letting one’s conscience be one’s guide. In this, we can admire her. Maybe, just maybe, she’ll even be remembered in a positive light.

That does not, of course, mean she is right.

She is not right about religious freedom—not by a long shot. Her stand at the Rowan County Courthouse, true to her conscience though it may be, was not a free exercise of religion. On the contrary, it was an act that, according to reason and the laws and founding principles of our nation, is exactly the opposite. It was an infringement on that freedom.

She is also not right about what Christian faith would demand. While she might not regard me—an openly gay minister who has been working for more inclusive and affirming stances toward LGBT people in my church and society—as a credible source, I would argue that even her conservative evangelical brand of Christianity does not at its heart tolerate behavior like hers.

Though Davis is now free from the confines of the Carter County Detention Center, it is not too late to reflect on her act of conscience and the cries of the thousands who gathered to celebrate it. It is also not too late for her to present a truer picture of biblical faith, one that both obeys its commandments and leaves her conscience intact.

The right of people to freely practice their religion was enshrined in the First Amendment’s protections—and, for most of our country’s history, in the largely unchallenged habits of Americans (at least when it comes to practicing conventional, mainstream Christian religion). This enshrinement has meant, among other things, that pastors preach what they want (and marry whom they want, not incidentally), that partakers of the Eucharist drink what they want, and that certain tribes smoke what they want.

For a long time, religious liberty wasn’t discussed much in the political news because the subject is so, well, religious. Until the last couple of years, that is.

To many today, “religious freedom” has come to mean the freedom to interfere on religious grounds. Today, “religious freedom” is given as grounds for an employer not to provide health care coverage. As a cover for parents who create a public health risk for other people’s children by not vaccinating their own. As a pre-emptive strike in support of the hypothetical florist who so abhors same-sex matrimony that he cannot abide giving it his imprimatur of calla lilies and hydrangeas.

These are complex cases, to be sure. They reflect a dynamic legal question that we will surely be sorting out for years to come.

But the Kim Davis case is uncomplicated: Religious freedom is no justification for a court clerk to refuse to issue marriage licenses in accordance with a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. In fact, religious freedom means exactly the opposite of what Kim Davis seems to think it means. Religious freedom protects couples from her. In the current drama, Davis is the state, and her infringement on the religious freedom of the couples appearing before her for licenses is the very definition of violating the First Amendment.

There are fair and practical questions here. Must Davis’ conscience really bind her actions as clerk, anyway? Does the IRS worker who processes tax returns bear moral responsibility for the wars those taxes support? Was Davis personally vouching for the moral character, practical wisdom, or even the legality of each of the marriages behind the licenses she freely signed in the past? If so, she bore a bigger responsibility than one might think a county clerk should be obliged to accept.

To be clear, Davis does get to enjoy certain religious freedom protections. No court can force her to issue licenses, and the judge who sent her to jail made no such demand. She had the option then, and still has it now, to resign as clerk. No one has a right to public office. Consider the numerous county clerks who resigned last summer in the week after the Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. Several of them made thoughtful public statements explaining that since they could no longer uphold the law of the land, they would do the only thing they could with a clear conscience: step aside. This is the real act of conscience—the act that earns you mention in the same breath as other great leaders who have sacrificed for a cause. If, of course, the cause was just.

I’ve been ordained for 16 years, including 13 years pastoring a congregation with whom I could not be fully open about my identity as a gay man because of denominational policies. For the last three years, I’ve led a national organization that has worked for LGBT inclusion in my denomination, the Presbyterian Church (USA). We’ve been pleased in the past year to play a part in giving our pastors and congregations the freedom to offer the blessing of marriage to all couples, regardless of gender. These changes in our church took effect just weeks before the Supreme Court made it a relevant issue in every single state.

Which is to say: I’m not a lawyer; I’m a minister. And what I’m struck by most in this national conversation around Kim Davis is not actually the debate about religious freedom. What strikes me most is the lack of conversation over the morality of her decision, the uncritical acceptance of the idea that her act of “conscience” is faithful and true to her religion. I’ve been struck by the people rallying around her outside the jailhouse during and after her incarceration, and their praise for the principles Davis has purportedly upheld so well.

Much can and will be written about Davis’ failure to demonstrate all manner of Christian virtues. How she did not show love and grace to the same-sex couples who stood before her. How there may have been some logs in her own eyes while she was identifying specks in the eyes of others. How her views conflict with ample biblical scholarship and a growing Christian movement—that includes many evangelicals—to support same-sex marriage as a faithful expression of covenant love.

Why have so few Christians—who can and do disagree about the morality of homosexuality—stood up and said what we almost all agree on—that it just isn’t okay to break promises? I don’t know any Christians—or, honestly, people of any religious faith—who would otherwise defend a failure to honor vows. Here, according to the Associated Press, is the vow taken by every county clerk in Kentucky upon assuming office:

“I, —————, do swear that I will well and truly discharge the duties of the office of ————— County Circuit Court clerk, according to the best of my skill and judgment, making the due entries and records of all orders, judgments, decrees, opinions and proceedings of the court, and carefully filing and preserving in my office all books and papers which come to my possession by virtue of my office; and that I will not knowingly or willingly commit any malfeasance of office, and will faithfully execute the duties of my office without favor, affection or partiality, so help me God.”

Filing and preserving all papers. Without partiality. So help her God.

The instruction not to bear false witness is one of the Ten Commandments of Judeo-Christian tradition. It grounds us in our relationships and allows our public officials to enjoy the confidence of the people they serve. When people in leadership do not do what they say they will do, the system breaks down, along with our trust in each other. And, our faith teaches, willful failure to honor our commitments is sin, which leaves us broken and disconnected from the source of our life, our joy, our hope.

Kim Davis is neither evil nor saintly. She is the county clerk of Rowan County, Kentucky, who has found herself in a firestorm not entirely of her making, for which she was not prepared. She has been at the mercy of ideological lawyers she did not hire, secular media prone to portray rural Christians as backward, and a brutal Twittersphere full of ad hominem attacks. In the midst of it all, she has sought to sound a moral voice of conscience, and for that she deserves some admiration, even though her views are mistaken. What she does not deserve is a pass from doing the right thing—keeping her promises, doing her job, or making the sacrifice that goes with her principled stand.

And religious leaders, rather than angling to stand by her side at a rally, should be holding her accountable for that.

Send A Letter To the Editors