A mother and child, residents of the Cabrini-Green public housing project in Chicago, play in a playground adjoining the project on May 28, 1981. Photo by Charles Knoblock/Associated Press.

In the 1992 horror film Candyman, Helen, a white graduate student researching urban legends, is looking into the myth of a hook-handed apparition who is said to appear when his name is uttered five times—“Candyman, Candyman, Candyman, Candyman, Candyman.” She ventures to the site where the supernatural slasher is supposed to have disemboweled a victim. Alone, of course, she enters a men’s public toilet at Cabrini-Green, which in real life was the city’s most infamous public housing complex. This solitary building, surrounded by sheer-faced towers, arouses a queasy feeling of both desolation and being watched by unseen multitudes.

Though Candyman is rumored to dwell inside one of the looming high-rises, what’s most terrifying here is really the idea of the inner-city location. Decades before writer-director Bernard Rose’s horror flick arrived in theaters, public housing for many Americans had come to represent the unruliness and otherness of U.S. cities. And Cabrini-Green stood as the symbol of every troubled housing project—a bogeyman that conjured fears of violence, poverty, and racial antagonism.

Like many mid-20th-century public housing projects across the Northeast and Midwest, Cabrini-Green was conceived as a model of civic redevelopment, and as a source for a more democratic form of urban living. It was built in stages on Chicago’s Near North Side beginning in the 1940s—first with barracks-style row houses and then, in the 1950s and 1960s, augmented by 23 towers on “superblocks” closed off to through streets and commercial uses. It contained 3,600 public housing units in total, with a population exceeding 15,000, packed tightly into a mere 70 acres of land.

The Cabrini-Green area, along the banks of the Chicago River’s North Fork, previously had been an industrial slum, home to a succession of poor immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Sweden, and southern Italy, in addition to a growing number of African Americans who had fled from the Jim Crow South. The smell of sulfur and the bright flames of a nearby gasworks had given the river district the nickname “Little Hell.” House fires, infant mortality, pneumonia, and juvenile delinquency all occurred there at many times the rate of the city as a whole.

Public housing was seen as a cure for the area’s decay and disrepair. At the dedication of the Cabrini row houses, in 1942, Mayor Edward Kelley declared that the modest and orderly buildings “symbolize the Chicago that is to be. We cannot continue as a nation, half slum and half palace. This project sets an example for the wide reconstruction of substandard areas which will come after the war.”

Then, as now, the for-profit real estate market had failed most low-income renters. During the 1940s, the rental vacancy rate in Chicago fell to less than one percent. A quarter of the existing homes were falling apart and needed to be replaced. In the city’s segregated black neighborhoods, families were excluded from the open housing market, and conditions there were even more dire. New public housing offered renters a kind of salvation—from cold-water flats, firetraps, and capricious evictions. For many families, the Chicago Housing Authority promise of a “decent, safe and sanitary home” felt like a leap into the middle class.

But as time went on, the Chicago Housing Authority, like many big-city authorities, was perennially underfunded and disastrously mismanaged. In Chicago, as elsewhere, high-rise developments were built intentionally in neighborhoods that were already segregated racially. After the 1950s, as large numbers of Chicagoans fled the city for the suburbs, and manufacturing jobs disappeared as well, public housing populations became poorer and more uniformly black. The amount collected in rent—as a proportion of a resident’s income—declined. Deficits ballooned; maintenance and repairs lagged.

The developments, with their isolation and high concentrations of poverty, were treated increasingly as isolated vice zones by both police and criminals. By the time of Candyman, Chicago was home not only to three of the country’s 12 richest communities but also, amazingly, to 10 of the country’s 16 poorest census tracts, all of them including large public housing complexes.

Partly because of its proximity to Chicago’s ritzy Gold Coast neighborhood, Cabrini-Green became “notorious” for crime, but this reputation was complicated. Other public housing developments in the city were larger, poorer, and had higher rates of crime. In the extreme segregation of Chicago, though, Cabrini-Green remained that uncommon frontier where whites still crossed paths with poor blacks. The complex was noted as a place to avoid, or to go to, for felonious offerings.

Cabrini-Green, therefore, entered the popular imagination as the embodiment of the “inner city,” becoming the setting of the prime-time sit-com Good Times, of movies, urban crime novels, documentaries, rap songs and endless media coverage. There was a recurring Saturday Night Live skit in the 1980s about a teenage single mother—her name was Cabrini Green Harlem Watts Jackson. The public housing project had made it onto a Mount Rushmore of scariest places in urban America.

What Candyman captures is this muddling of what is real and imaginary. Cabrini-Green was both an actual place with an array of serious problems, and a nightmare vision of fear and prejudice. A horror movie is often about what isn’t seen; it requires menacing visions to fill in the shadows of the unknown. The real Cabrini-Green had plenty of violent crime, but it was also home to thousands of families who had formed elaborate support networks and lived everyday lives. The fictional Cabrini-Green in which people believed in a murderous, hook-handed spirit was the pure creation of that fear. “The old dark house on the hill has always been the standard setting of horror,” director Rose explained. “But it seemed to me that the big public housing project was the new venue of terror.”

Rose created an elaborate backstory for his film’s killer that tapped into numerous racial tropes. In his previous life, Candyman was a gifted portrait artist, the son of a slave at the turn of the 19th century whose father earned a fortune after the Civil War by inventing a means to mass-produce shoes. Candyman fell in love with and impregnated one of his subjects, a white woman, and the girl’s father hired thugs to lynch him, chasing him to the site of the future Cabrini-Green, sawing off his painting hand before setting him on fire. In his reincarnated form, Candyman (Tony Todd) appears in the movie gaunt-cheeked, towering in a fur-lined trench coat, possibly as hell-bent on miscegenation—Virginia Madsen’s Helen is a dead ringer for his postbellum beloved—as on murder.

“Just as urban legends are based on the real fears of those who believe in them, so are certain urban locations able to embody fear,” Chicago film critic Roger Ebert wrote in his three-out-of-four-star review of the movie in the fall of 1992.

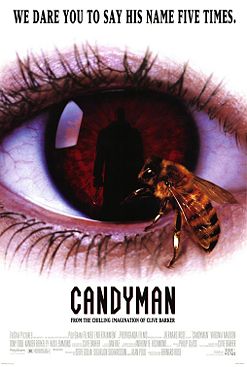

Poster for the 1992 horror film Candyman. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Candyman arrived in theaters as the very meaning of “inner city” was already changing again, a signifier not only of danger but of wealth and a mounting wave of gentrification. At the beginning of the 1990s, Chicago’s population ticked up for the first time in 40 years. The area around Cabrini-Green was booming with new development and an influx of young white professionals. It’s at this moment that the ghetto actually became scarier. The era’s yuppies inhabited “transitioning” neighborhoods, and reports of crime were being imagined as near-misses—just a wrong turn away. You can see these anxieties in the alarm bells then sounding over the coming tides of “crack babies,” “wilding” teens, and “super-predators” (as well as in other similar films of the era such as After Hours and Judgment Night).

In one scene in Candyman, Helen reads about a real-life crime that occurred in Chicago public housing: A man was able to enter neighboring apartment units through connected bathroom vanities so cheaply constructed that he simply pushed in the mirrors to create a passageway. Returning home, she discovers that in her own high-end condominium bathroom the same is true. Helen learns that her building was originally part of Cabrini-Green. It’s a preposterous plot turn that feels true to the moral panic of the moment. In only a matter of time, Candyman himself invades her apartment.

In the years since Candyman came out, more than 250,000 units of public housing have been demolished across the United States. The last Cabrini-Green tower—and the final public housing high-rise in Chicago not reserved for the elderly—came down in 2011. The clearing of these high-rises was touted as an effort to revive the city and to rescue the families who had been trapped in the generational poverty of public housing. Mayor Richard M. Daley promised that former residents would now be able to share in the benefits of the resurgent city. “I want to rebuild their souls,” he declared.

Less looming mixed-income developments—blending market-rate and heavily subsidized households—replaced many of the same public housing buildings that were used to clear the slums of a half-century before, but by design, only a small number of the old tenants were able to move into the new buildings. With Section 8 housing vouchers, most former residents (along with their souls) ended up renting private housing in predominantly black and under-resourced sections of Chicago’s South and West sides. The demolitions didn’t do away with the poverty and isolation that afflicted the city’s public housing; these problems were moved elsewhere, becoming less visible and no longer literally owned by the state.

Today, only one in five U.S. families that are poor enough to qualify for a subsidy receive any sort of government support as city rents rise while wages for all but the highest earners stagnate. Half of all renters now pay more than 30 percent of their income for rent; a quarter pay more than 50 percent. Fewer and fewer people can afford to live close to the economic activity of the inner city. For the first time, the United States has a greater number of poor people living in suburbs than in cities.

At the end of Candyman, the residents of Cabrini-Green gather together outside their high-rises and light an immense bonfire. It’s a purge that exorcises the phantasm as well as the horrors of public housing. In 2014, twenty-two years after the film’s release, the Chicago Housing Authority opened up a lottery for people to get onto the waiting list for either a public housing unit or a voucher. Despite the stigma of dysfunction, danger, and dilapidation, one in four of Chicago’s million households entered the lottery for a Chicago Housing Authority home. The real horror of people going without adequate housing remains.

“Candyman. Candyman. Candyman. Candyman….”

Send A Letter To the Editors