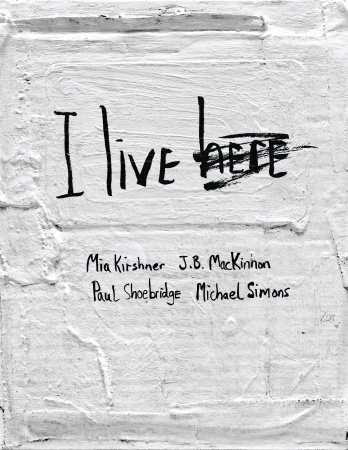

I Live Here

by Mia Kirshner, J.B. MacKinnon, Paul Shoebridge, and Michael Simons

On its back cover, I Live Here is called a “paper documentary.” It is something other than a book, encased in a book-shaped box. Inside are four small paperbacks, the size of school notebooks; the first carries, appropriately, the mottled black-and-white of a composition book on its cover. Each book contains the story of people – particularly women and children – in places of conflict, told through journals, interviews, stories, photograhs and art, a collaboration between graphic novelists, writers, an actress, and the people themselves, with proceeds from sales going to Amnesty International.

The first pages of the first book, which profiles refugees in Chechnya, attempts to prepare us for the brutality of all the pages to come. Mia Kirshner, a film and television star whose father was born in a refugee camp, writing in a scrawl-like font on yellowed journal pages (as she does in all four books), asks of the men who beheaded four westerners: “What would lead one person to do this to another?” Moments later, accosted by a man, she sees “the possibilities of his violence and rage.” He simply tells her she dropped her pens.

Throughout the books we occasionally see those who commit violence. There is a husband, a thick-headed cartoon in a graphic novella, who nearly kills his wife after being tortured by soldiers; another brutal man is drawn by his son with wide eyes and gritting teeth. In the book on Burma, focusing on women forced into sexual slavery, rapists are shadowy, expressionist smears on the page. The most jarring, perhaps, are the murderers of disappeared women in Ciudad Juarez – photographed dolls with dull faces, on the opposite page from their victims, also depicted as dolls, bloodied and exposed.

Primarily, though, the collection is about those who survive and how they manage. Chechnyan refugees’ speak of their living conditions, depicted in cartoons and collaged photographs and words – food tied from rafters to keep out rats, single gas stoves to cook meager rations for large families. One man says, in cartooned bubbles, “Don’t build two story houses. Don’t buy too many things. You lose everything after such hard work.” A Burmese woman who survives rape says, in plain type on ripped-out notebook paper, “Like my mother before me, I have learned to hide everything deep in my heart.” One young imprisoned boy in Malawi writes, in the final book’s last pages, “The wealth of this country is in the soil and the health is in the spirit.” (The final book is strangely hopeful, including a beautiful and sad children’s story by J.B. MacKinnon, in which a baby is born in a graveyard and a young boy dies of starvation, pink butterflies fluttering over him.)

Sometimes, the compilers, particularly Kirshner, make us deliberately aware of our place, reading in a safe, faraway world. She writes in her journals of the “swagger” of foreign correspondents who trade in how much they’ve endured, even when surrounded by those who have endured far worse, and have no one to tell. Kirshner speaks of “dense and theoretical and well intentioned” seminars on disappeared women. And she concludes one journal with sad and shameful honesty, with a sentiment most readers might feel as well: “What do I do about the fact that I’m going home to try to forget what I’ve seen? I want to worry about my hair turning gray.”

Further Reading: A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier and We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda

Send A Letter To the Editors