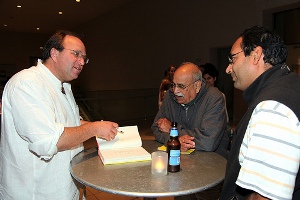

When he set out to write Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India 18 months ago, William Dalrymple hoped to find a Bengali man legendary for his skull collection.

“Being a latent Orientalist, this sounded like very promising material,” Dalrymple said to the crowd at the Hammer Museum.

Dalrymple found the skulls and their keeper, Tapan Goswami, who fed the skulls rum, whiskey and lentils, painted them red to stop them from molding in the monsoon, and was initially open chatting with Dalrymple until he suddenly clammed up. When pressed, Goswami said to Dalrymple, “It’s not you I’m worried about, it’s my two boys – they’re ophthalmologists in New Jersey. They say, ‘Dad you must stop going on about this black magic stuff.'”

In other words, as Dalrymple said, “It’s tough being an Orientalist these days. You go searching for these guys and you find out they’ve got cousins at the Hammer.” Dalrymple explored through the stories of three individuals the ways in which old India, its monks, dancers, and mystics, remains intact – if deeply affected by – the new India and the broader world.

Passports courtesy Mick Jagger

As Dalrymple noted, much has been written about the new India. Its economy is growing at a galloping pace, and according to some estimates will overtake the U.S. by 2050. However, as Dalrymple noted in Q&A, the growth is uneven, relying on “an elite of supertechies” rather than a large manufacturing base like China’s. Still, he said, it is a hopeful time and an “astonishing transition.”

As Dalrymple noted, much has been written about the new India. Its economy is growing at a galloping pace, and according to some estimates will overtake the U.S. by 2050. However, as Dalrymple noted in Q&A, the growth is uneven, relying on “an elite of supertechies” rather than a large manufacturing base like China’s. Still, he said, it is a hopeful time and an “astonishing transition.”

Dalrymple went after the old India – “the strange vocations, all the different ways of being Indian,” he said. “What happened to those fakirs on their nail beds you read about in 19th-century picture books?” Sometimes when Dalrymple found such men, he found contradictions like the one above. He and his wife encountered a “picture-perfect naga sadhu,” for instance, who spoke perfect English, had an MBA, and once worked selling refrigerator parts in Bombay. Two of the “gnarled old minstrels from Bengal” he interviewed, who lived in huts near a cremation ground, had passports. When Dalrymple asked why, they replied, “Some English singer got us over 20 years ago for an event. Called Mick something.” It was Mick Jagger’s party for the Beggars Banquet album release.

“There is a whole world in transition, suspended between modernity and tradition,” Dalrymple said.

Mad and sightless

Among all the traditions he encountered, Dalrymple said, “If I had to convert by force to any of these religions I might well become a Baul.” The term means “madmen” in Bengali, he said, and their philosophy is a palimpsest of all the cultures that passed through Bengal – Vaishnava Hinduism, Sufi Islam, Tantra, and Buddhism. Bauls travel from village to village singing songs. They believe in no eternal deity, and that attending a place of worship or praying to an idol is useless. “The only God that there is, is the heart of the man,” Dalrymple said. “To discover yourself – it’s very Californian, and yet its 600 years old.”

Dalrymple reported on a pair of Baul friends from opposite ends of village society. Kanai was the son of a landless Dalit laborer, who became blind from smallpox and lost his family to accidents and suicide before he joined the Bauls. Debdas was the son of a Brahmin so conservative that he “disinfected” cigarettes made by his Muslim friend by touching them against cow dung. Debdas became a Baul after attending a great festival that, Dalrymple said, “makes Woodstock look like a kind of Rotarian dinner,” where 25,000 musicians gather and get high and sing. Debdas’ family disowned him, and he in turn gave up his caste. The two friends were separated only once – when Debdas became obsessed with trying to live without food. He managed to stop eating entirely, until he became delusional. Kennai had a premonition of his friend in danger and saved him. As Dalrymple quoted, “Sometimes the mad and sightless can understand things better than the sane and sighted. The blind are never deceived by appearances.”

Dalrymple reported on a pair of Baul friends from opposite ends of village society. Kanai was the son of a landless Dalit laborer, who became blind from smallpox and lost his family to accidents and suicide before he joined the Bauls. Debdas was the son of a Brahmin so conservative that he “disinfected” cigarettes made by his Muslim friend by touching them against cow dung. Debdas became a Baul after attending a great festival that, Dalrymple said, “makes Woodstock look like a kind of Rotarian dinner,” where 25,000 musicians gather and get high and sing. Debdas’ family disowned him, and he in turn gave up his caste. The two friends were separated only once – when Debdas became obsessed with trying to live without food. He managed to stop eating entirely, until he became delusional. Kennai had a premonition of his friend in danger and saved him. As Dalrymple quoted, “Sometimes the mad and sightless can understand things better than the sane and sighted. The blind are never deceived by appearances.”

Part-time gods

Many of these religions traditions are still highly segregated by region, Dalrymple noted. And the most spectacular such form he saw was an incarnational dance in the state of Kerala, in which Dalit dancers take on the role of deities for a few months a year. Dalrymple described seeing one such performance and speaking to the dancer, Hari Das. When Dalrymple finds Hari Das, Das is lying mostly naked on a mat, having makeup applied to his face to transform him into the god Vishnu. When Dalrymple asks Das if he is nervous, Das answers, “It’s more the fear that he might refuse to come. The intensity of your devotion determines the intensity of the possession. If it becomes even once routine, the gods may stop coming.” Das describes the dance as a blinding light, a trance, until the end, which he says is “like the incision of a surgeon.”

Dalrymple also learns that Das spends most of the year as a well-digger and prison warden. “I’m poor enough to do anything if it pays my wage,” Das tells him, describing the prison as chaotic, a battleground between rival extreme right and left political parties. But for two months, Das is a “part-time god,” whom even Brahmins worship. “It’s a safety valve,” Dalrymple said during Q&A, of the flipped caste hierarchy the dance represents. “It is not unlike Carnival in Europe – where the sexual structure is inverted for a period of time.”

Lace and lattice

Dalrymple also studied one branch of Muslim tradition. The Sufis, he said, “are the great underrated force of South Asian Islam.” While Americans are only vaguely aware of Sufism – of Rumi and mystic poetry – Sufi shrines in South Asia are nearly as important as mosques. “Women come and tie lace around a lattice asking for a job for their husband or child or marriage for a daughter,” he said. The shrines also serve a social function. “In the West, if you fall through the cracks, you end up in a sleeping bag outside a Wal-Mart,” he said. “In India, you sit in the cremation ground and you’re treated as a divine being. It’s not a bad solution to a universal problem.”

Dalrymple also studied one branch of Muslim tradition. The Sufis, he said, “are the great underrated force of South Asian Islam.” While Americans are only vaguely aware of Sufism – of Rumi and mystic poetry – Sufi shrines in South Asia are nearly as important as mosques. “Women come and tie lace around a lattice asking for a job for their husband or child or marriage for a daughter,” he said. The shrines also serve a social function. “In the West, if you fall through the cracks, you end up in a sleeping bag outside a Wal-Mart,” he said. “In India, you sit in the cremation ground and you’re treated as a divine being. It’s not a bad solution to a universal problem.”

Sufism in South Asia is heavily influenced by Hindu mysticism, and they preach that all religions are different manifestations of the same reality. In various Sufi poems, the mullah is portrayed as either a contemptible “legalistic puritan” or a figure of fun. Today of course, Dalrymple said, mullahs are empowered in part due to funding from the U.S., Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia beginning decades ago. Extremists attack Sufi shrines in the Middle East, if not in South Asia thus far. Wahhabism has also spread, equated with status and wealth. “The equivalent in the Christian world would be if oil was found underneath some particularly vile Serbian Orthodox warlord,” he said. “That fringe sect suddenly [finds] itself as the most powerful force in the Christian world.” When Dalrymple visited one Sufi, Sain Fakir, he insisted that Sufi poems are the “essence of the spirit of the Koran,” which Fakir said was sometimes difficult to understand and thus easily distorted. Fakir praised Sufism as understanding of human weakness, of the reality of sin, of forgiveness.

And they have a telling notion of hell. As one woman told Dalrymple, a Sufi folk story describes when the saint Lal Shahbaz Qalandar tried to go to hell to find fire for warmth on Earth. Dalrymple quoted: “There is no fire in hell. Everyone who goes there brings their own fire, and their own pain, from this world.”

Watch the video here.

Watch a highlight clip here.

See more photos here.

Buy the book here.

Read an excerpt here.

Read Dalrymple’s In The Green Room Q&A here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors